“Stop and Frisk” case plaintiffs (L-R) Nicholas Peart, Lalit Clarkson, Leroy Downs, Devin Almonor and David Ourlicht pose for the media after a news conference at the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York, August 12, 2013. REUTERS/Eduardo Munoz

A judge rules that the NYPD’s practice of stopping, questioning and frisking young black and Latino men violates the Fourth Amendment

AlterNet / By Kristen Gwynne

AlterNet / By Kristen Gwynne

August 12, 2013 |

On Monday, a decade-long battle to curb the New York Police Department’s racial profiling of young, black and Latino men reached a historic turning point. Federal judge Shira Scheindlin ruled that New York City has routinely and systematically violated the Constitution by unlawfully stopping, and often frisking, young men of color.

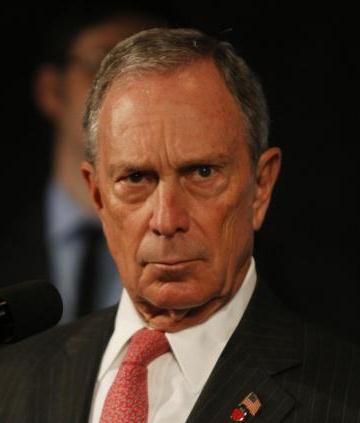

Scheindlin’s striking decision in the class action lawsuit, Floyd v. City of New York, delivers a severe blow to the racially discriminatory policies of Mayor Michael Bloomberg and NYPD Commissioner Ray Kelly, whose police practices have led to humiliation and harassment in New York communities.

Scheindlin’s 195-page decision [3] explained that the NYPD’s practice of stopping, questioning and frisking young black and Latino men violates 4th Amendment law mandating reasonable suspicion for a search. Rather than targeting individuals in the process of committing a crime, the NYPD targeted all young black and Latino men in their jurisdiction. The city, Scheindlin said, “adopted a policy of indirect racial profiling by targeting racially defined groups for stops based on local crime suspect data.” The policy violated not only the 4th Amendment rights of New Yorkers, but their 14th Amendment protections as well.

The ruling does not deem stop-and-frisk unlawful as a police tool (in fact, it’s used in police departments everywhere) but acknowledges that its enforcement has not been in line with Supreme Court decisions outlining the tactic’s legal use.

Scheindlin ordered as part of the injunctive relief (no monetary damages were filed) that a court-appointed monitor oversee stop-and-frisk, and mandated a Joint Remedial Process, complete with a facilitator, to include input from stakeholders like residents in communities with high volumes of stops. The ruling also mandates a one-year pilot program of police officer-worn cameras in one precinct per borough, whose recordings, Scheindlin wrote, “may either confirm or refute the belief of some minorities that they have been stopped simply as a result of their race, or based on the clothes they wore, such as baggie pants or a hoodie.”

Bloomberg’s Propaganda Machine

The NYPD stopped more than 684,000 people in 2011, marking a 600 percent increase from Bloomberg’s first year in office in 2002. Nearly ninety percent of those stopped have been Black or Latno. Scheindlin found that plaintiffs proved an “action pursuant to official municipal policy” caused the constitutional violations, and held Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration responsible not only for enforcing the lawless behavior, but intentionally ignoring and downplaying evidence of widespread misuse and damage to communities.

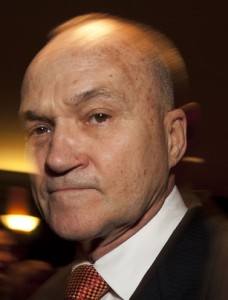

Under the NYPD’s policy, targeting the ‘right people’ means stopping people in part because of their race. Together with Commissioner Kelly’s statement that the NYPD focuses stop and frisks on young blacks and Hispanics in order to instill in them a fear of being stopped, and other explicit references to race,” wrote Scheindlin, “there is a sufficient basis for inferring discriminatory intent.”

The judge’s decision is troubling news for Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who has already vowed to appeal the ruling. Bloomberg continued his longstanding, heated campaign to smear Scheindlin—as well as multiple critics of stop-and-frisk—when he accused of the judge of not giving the city “a fair trial” this afternoon.

While Bloomberg has repeatedly claimed that stop-and-frisk is an essential tool for deterring gun violence, Scheindlin stated as fact that less than 2 percent of stops from 2004 to 2011 uncovered a weapon. She added that nearly 9/10ths of all stops resulted in no further law enforcement action, like a summons or arrest, suggesting via the NYPD’s own data that officers rarely have the suspicion necessary to make these stops.

Unfounded police stops, searches and seizures are one of the primary reasons this state and country’s prison population is booming.

Still, Scheindlin has emphasized that the case is not about whether the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk policy works or saves lives, but the constitutionality of police behavior.

“The goals of liberty and safety may be in tension, but they can coexist — indeed the Constitution mandates it,” she wrote in the ruling. Moreover, she said the case is not primarily about the 19 stops that were the subject of testimony at trial, but “policy” or “custom” of violating the Constitution with unlawful stops and frisks.

It is “important to recognize the human toll” of unconstitutional stops, said Scheindlin. “While it is true that any one stop is a limited intrusion in duration and deprivation of liberty, each stop is also a demeaning and humiliating experience. No one should live in fear of being stopped whenever he leaves his home to go about the activities of daily life,” she wrote.

Youth in Highland Park outside school board meeting where dozens of their teachers were laid off. Photp 4 29 2004.

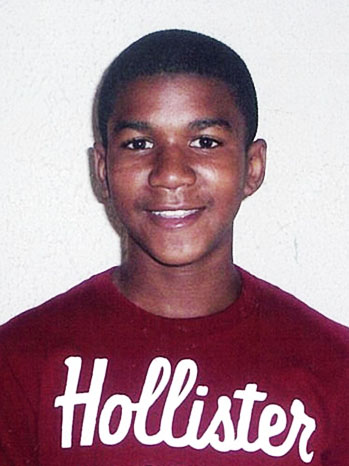

Scheindlin linked the ruling to the national struggle for the humanity of young men of color, who are far too often deemed suspicious or guilty without reason. In a nod to NYPD testimony claiming that suspect descriptions for young black men allow for race-based targeting by police, Scheindlin rejected Bloomberg’s rhetoric that stop-and-frisk must target color to be effective.

“Rather than being a defense against the charge of racial profiling, however, this reasoning is a defense of racial profiling,” wrote Scheindlin. “To say that black people in general are somehow more suspicious-looking, or criminal in appearance, than white people is not a race-neutral explanation for racial disparities in NYPD stops: it is itself a racially biased explanation. This explanation is especially troubling because it echoes the stereotype that black men are more likely to engage in criminal conduct than others.”

Noting the prevalence and damage of racist stereotyping, Scheindlin references in the footnotes Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow, and goes on to quote from Obama’s impromptu speech following George Zimmerman’s acquittal:

Noting the prevalence and damage of racist stereotyping, Scheindlin references in the footnotes Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow, and goes on to quote from Obama’s impromptu speech following George Zimmerman’s acquittal:

“There are very few African-American men in this country who haven’t had the experience of being followed when they were shopping in a department store. That includes me. There are very few African-American men who haven’t had the experience of walking across the street and hearing the locks click on the doors of cars. That happens to me, at least before I was a senator. There are very few African-Americans who haven’t had the experience of getting on an elevator and a woman clutching her purse nervously and holding her breath until she had a chance to get off. That happens often.”

Scheindlin also referenced a New York Times op-ed [4] by Ekow N. Yankah:

FILE – In this Aug. 4, 2009 file photo, Detroit Chief of Police Warren Evans, right, and team stop a vehicle in Detroit. On any given day or night, dozens of Detroit’s toughest, most street-savvy officers descend on high-crime areas to round up as many illegal guns, drugs and bad guys as possible in one swoop with tactics as simple as minor traffic stops. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio, File)

“What is reasonable to do, especially in the dark of night, is defined by preconceived social roles that paint young black men as potential criminals and predators. Black men, the narrative dictates, are dangerous, to be watched and put down at the first false move. This pain is one all black men know; putting away the tie you wear to the office means peeling off the assumption that you are owed equal respect. Mr. Martin’s hoodie struck the deepest chord because we know that daring to wear jeans and a hooded sweatshirt too often means that the police or other citizens are judged to be reasonable in fearing you.”

Speaking at an emotional press conference Monday afternoon, plaintiffs in the suit made clear the human toll Scheindlin references in her decision. “I could’ve been like Trayvon Martin,” said plaintiff Devin Almonor. Similarly, plaintiff David Ourlicht linked the practice to the “polarization of people of color” in “America as a whole.” Upon hearing the decision Monday morning, Ourlicht told the press, “The first thing I did was cry.” Struggling to find the right words, Ourlicht expressed relief in hearing his struggle “recognized.”

Scheindlin cited the stop of Cornelio McDonald as evidence of “the NYPD’s policy of indirect racial profiling based on crime suspect data.” Aware that black males had been burglarizing residences and committing armed robberies in Queens, Officer Edward French stopped McDonald because he matched suspect descriptions.

As Scheindlin notes, “McDonald was a black man crossing the street late on a winter night with his hands in his pockets, and as a black man he was treated as more suspicious than an identically situated white man would have been. In other words, because two black males committed crimes in Queens, all black males in that borough were subjected to heightened police attention.”

She noted that, in 2009, NYPD Officer Edgar Gonzalez checked “fits description” on 132 UF-250s (forms officers are supposed to fill out after every stop), though none of those stops were based on ongoing investigations or radio runs through which he might have learned a suspect description. “Nonetheless,” Scheindlin wrote, “Gonzalez’s supervisor, then-Sergeant Charlton Telford, testified that he was not concerned by this discrepancy,” insisting that the stops were based on “the race, the height, [and] the age” of suspects.”

A long campaign was conducted in the streets of New York against “Stop and Frisk” before ruling was handed down.

At the time of the stops, suspect description for burglaries was a male Hispanic (height 5’8″/5’9″), while robbery suspects were four to five black males ages 14 to 19, and shootings was a black male in his 20s. “Perhaps as a result of Officer Gonzalez’s reliance on this general suspect data, 128 of the 134 people he stopped were black or Hispanic,” wrote Scheindlin. “This is roughly in line with the percentage of 295 criminal suspects in his precinct who are either black or Hispanic (93%), but far exceeds the percentage of blacks and Hispanics in the local population (60%).”

“Thus, Officer Gonzalez’s 296 UF-250s provide a perfect example of how racial profiling leads to a correlation between the racial composition of crime suspects and the racial composition of those who are stopped by the police. By checking ‘Fits Description’ as a basis for nearly every stop, Officer Gonzalez documented what appears to be a common practice among NYPD officers — treating generic crime complaint data specifying little more than race and gender as a basis for heightened suspicion,” Scheindlin concluded.

She also noted Senator Eric Adams’ testimony that NYPD Commissioner Kelly once told him he targeted young black and Hispanic men “to instill fear in them that every time that they left their homes they could be stopped by police.”

Scheindlin said she found Adams’ testimony “credible,” especially because Kelly decided not to appear at the trial to rebut the claim. “In fact, the substance of Commissioner Kelly’s statement is not so distant from the City’s publicly announced positions,” said Scheindlin, who went on to add:

Mayor Bloomberg stated in April that the NYPD’s use of stop and frisk is necessary “to deter people from carrying guns. . . . [I]f you end stops looking for guns…there will be more guns in the hands of young people and more people will be getting killed.” At the same time, the City emphasized in its opening arguments that “blacks and Hispanics account for a disproportionate share of …crime perpetrators,” and that “90 percent of all violent crime suspects are black and Hispanic.” When these premises are combined — that the purpose of stop and frisk is to deter people from carrying guns and that blacks and Hispanics are a disproportionate source of violent crime — it is only a short leap to the conclusion that blacks and Hispanics should be targeted for stops in order to deter gun violence, regardless of whether they appear objectively suspicious. Commissioner Kelly simply made explicit what is readily inferrable from the City’s public positions.

Scheindlin said that an analysis of UF-250s revealed that at least 200,0000 stops were made without reasonable suspicion between January 2004 and June 2012. That being said, Scheindlin added that, “The actual number of stops lacking reasonable suspicion was likely far higher,” because UF-250s allow officers to articulate reasonable suspicion with a series of check boxes indicating vague reasons for stops like “furtive movements,” thus giving the officers the benefit of the doubt and failing to provide “individualized” proof.

As Scheindlin notes, officers checked furtive movements for 42% of forms, and high crime area for 55% of forms—all of which were not included as “apparently unjustified” in the analysis from which she draws the 200,000 figure.

Facing two conflicting statistical analyses of stop-and-frisk by race, Scheindlin found that the city’s interpretation of data was severely flawed. The NYPD had used suspect descriptions as the “benchmark” for determining if stops were completed with reasonable suspicion, but independent reviewers found this data point flawed because it did not incorporate people on the street available to be stopped.

“There is no basis for assuming that an innocent population shares the same characteristics as the criminal suspect population in the same area,” said Scheindlin. “Instead, I conclude that the benchmark used by plaintiffs’ expert — a combination of local population demographics and local crime rates (to account for police deployment)—is the most sensible.”

Scheindlin concluded from expert testimony that, “The NYPD carries out more stops where there are more black and Hispanic residents, even when other relevant variables” like crime “are held constant.”

Blind Eye

The long Floyd trial included nine weeks of testimony and more than 100 witnesses, the majority of whom were NYPD officials. Scheindlin said senior police department officials broke the law “through their deliberate indifference to unconstitutional stops, frisks and searches.”

“They have received both actual and constructive notice since at least 1999 of widespread Fourth Amendment violations occurring as a result of the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk practices. Despite this notice, they deliberately maintained and even escalated policies and practices that predictably resulted in even more widespread Fourth Amendment violations,” she wrote in the decision, adding, “The NYPD has repeatedly turned a blind eye to clear evidence of unconstitutional stops-and-frisks.”

The lawsuit stems from a 1999 federal class action suit, Daniels v. City of New York, that challenged the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk practices shortly after the highly publicized police shooting of unarmed 23-year-old Amadou Diallo, whose wallet police claim to have mistaken for a gun. Scheindlin was assigned the the Daniels case by the spin of a wooden wheel, and since then, “related-case rule” has sent similar cases, like Floyd, into her courtroom (to the dismay of Mayor Bloomberg).

The Danielssettlement required the NYPD to implement a written policy banning racial profiling, and establish an audit in which stops may be reviewed by supervisors to determine reasonable suspicion. The Center for Constitutional Rights, the group that filed Floyd, says the NYPD not only failed to follow the settlement by adequately investigating stops, but also escalated the NYPD’s policy of unconstitutional stops.

In the Floyd case testimony for example, recently retired NYPD Chief of Department — highest-ranking uniform member of the NYPD from 2000 until March 2013 — Joseph Esposito said he could not recall ever discussing the racial disparity in stop-and-frisk with his boss, NYPD Commissioner Ray Kelly. In fact, as I wrote in April [5], Esposito said he did not even remember uttering the phrase “racial profiling” at the monthly NYPD meetings over which he presided. He also could not recall being made aware of the New York Attorney General’s 1999 finding that Blacks and Latinos were “over-stopped.”

And even after the ruling, the NYPD keeps its head in the sand. On Monday, Commissioner Kelly called accusations of NYPD racial profiling “recklessly untrue,” adding that “We do not engage in racial profiling, it is prohibited by law, it is prohibited by our own regulations. We train our officers that they need reasonable suspicion to make a stop, and I can assure you that race is never a reason to conduct a stop.”

At a press conference Monday, City Councilperson and advocate of the police-reform-oriented Community Safety Act Bloomberg vetoed (though an override is in process), Jumaane Williams urged the Mayor to step up and “show leadership” by acknowledging laws in the stop-and-frisk practice, and allowing reforms to take place. “Their own COMPSTAT statistics show that the current implementation of stop, question and frisk did little to get guns off the street and prevent gun violence,” Williams wrote in the New York Daily News [6], “These practices, employed under a tone-deaf administration, have made our police officers an unwelcome presence in some communities.”

Williams has long maintained that nobody wants crime to decrease more than people living in communities most affected, and that Bloomberg should listen to complaints of residents in the areas he claims to be protecting.

“As we employ the NYPD to continue to do good police work, we need to address the underlying causes of gun violence and crime. All reasonable people of goodwill want an end to gun violence in our communities — whether it is a street corner on Church Ave. or a school house in Connecticut. However, as our Constitution makes emphatically clear, we cannot trample on the civil rights of the many just to get to the few who endanger us,” Williams wrote.