DAREA members disembark from bus in Cincinnati June 15, 2016. In center is DAREA President Bill Davis, to his right is DAREA VP Cecily McClellan, to his left is retiree Ezza Brandon. They were allowed to wear their “Hands off my Pension” T-shirts in the 6th Circuit courtroom as arguments on bankruptcy appeals were heard. The bus was full, with over 40 retirees.

Detroit bankruptcy “Grand Theft” is not a done deal

6th Circuit Judges appeared generally favorable to retiree attorneys’ arguments

DAREA may return Aug. 4 for oral arguments on Phillips v. Snyder, which challenges Public Act 435, Michigan’s “Emergency Manager law”

By Diane Bukowski, VOD editor, City of Detroit retiree

June 27, 2016

DAREA members show their fighting spirit on the bus. The ride took a little over 4 hours, taking off from the parking lot of the Dearborn Public Library.

Cincinnati, Ohio – City of Detroit retirees are doggedly pursuing the battle to overturn the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history, carried out in the largest Black-majority city in the country in 2014. On June 15, a busload of Detroit Active and Retired Employee Association (DAREA) members traveled to Cincinnati to hear oral arguments at the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in five cases challenging the bankruptcy.

Impoverished by pension, annuity, and health care cuts that have led to a wave of similar cuts across the U.S., and angered that their city has been stripped of virtually all of its public assets, they said they wanted to be there to let the judges know, in the words of DAREA’s slogan, “We fight because we’re right!”

“We definitely made a major impact at the court,” DAREA president Bill Davis told VOD. “We packed the courtroom so thoroughly they had to bring out extra chairs for our people, and there were even a couple of us sitting on the floor. Many people wore our ‘Hands Off Our Pensions’ T-shirts in court.”

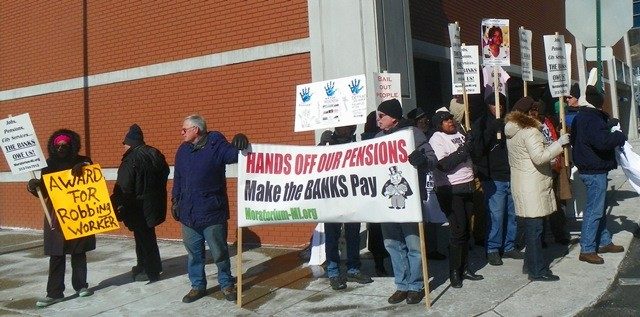

Demonstration during Detroit bankruptcy hearings.

Davis said DAREA will likely return to Cincinnati Aug. 5, when the Sixth Circuit will hear the appeal of a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Michigan’s Public Act 436, known as Phillips v. Snyder. Without that act, better known as the “emergency manager law,” the state takeover of most of Michigan’s Black-majority cities, the declaration of Detroit’s bankruptcy by its Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr, and the lead poisoning of the city of Flint its Emergency Manager cut ties with the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department would not have happened.

That lawsuit was re-filed after U.S. District Judge George Caram Steeh denied all but one argument in the suit, the fact that PA 436 has led to racial discrimination. See

“We’re willing to go and fight anywhere for democracy in Michigan,” Davis said.

6th Circuit Judge Alice Batchelder

Judge Karen Nelson Moore

Judge David McKeague

Sixth Circuit Judges Alice Batchelder, Karen Nelson Moore, and David McKeague are considering both oral arguments and briefs in the retiree cases.

The appeals were filed by five entities, the Ochadleus Group of Retirees, 146 strong, represented by attorney/retiree Jamie Fields (#15-2194), retiree William Davis, representing hundreds of DAREA retirees pro se (#15-2379), attorney/retiree John Quinn (#15-2337), attorney/retirees Dennis Taubitz and Irma Industrious, (15-2353) and retiree Lucinda Darrah pro se (15-2371).

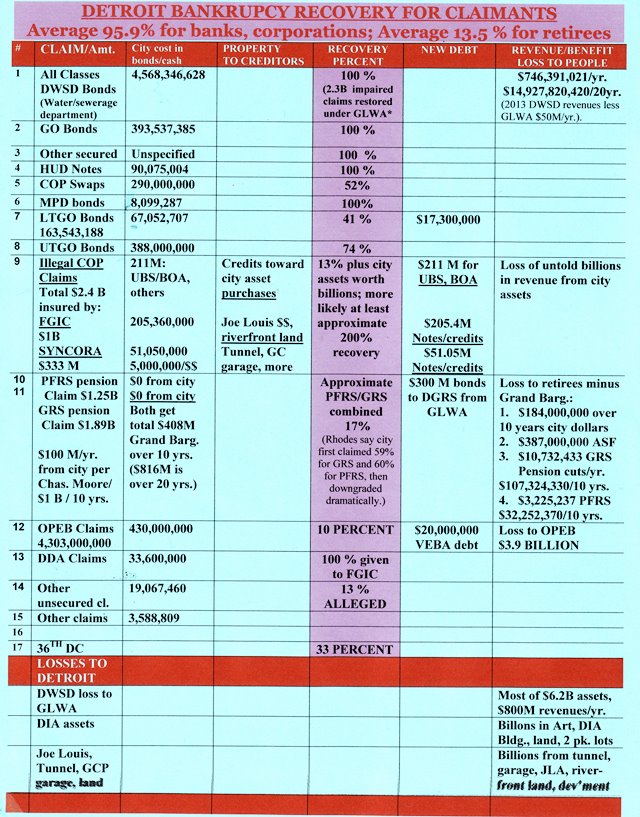

The groups involved have filled in a breach on the battle lines left by City of Detroit unions and retirement systems, which earlier withdrew their appeals of U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Steven Rhodes’ ruling that Detroit was eligible for bankruptcy and could cut pensions in violation of state law, the first time any judge in the U.S. had so ruled. They eventually agreed to adopt the disastrous bankruptcy plan of confirmation, with 70 percent of its cuts to creditors borne by retirees.

Ezza Brandon (r) tells Michigan AFSCME Council 25 Pres. Al Garrett it should not have withdrawn appeal of bankrupty eligibility decision, during protest July 31, 2014.

The unions and retirement systems ignored a scathing report by former Goldman Sachs banker Wallace Turbeville of DEMOS, which said Detroit was not bankrupt, that it only had a cash shortfall of $147 million, easily remedied. That report also said the city’s retirement systems, as independent bodies, should never have been included in the bankruptcy case. (See link below story.)

In withdrawing their appeal of Rhodes’ decision on bankruptcy eligibility, the unions and pension systems also wrote off powerful amicus briefs filed by the CalPERS, the largest pension system in the country representing California’s public employees, the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), and others.

“I think their withdrawal had a major impact on city retirees,” Davis said. “Had they gone through with their appeals, we wouldn’t have to be going through this using resources raised by just a few thousand retirees. Orr said we could not appeal the bankruptcy plan, but we have proven that is crazy. Of course you can appeal. How can you go into bankruptcy and lose all the city’s assets without being able to go to a higher court? This is nothing but a grand theft, and I believe we will ultimately find that a criminal conspiracy in violation of RICO [the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act] was carried out by Orr, Snyder, and [former State Treasurer] Andy Dillon was carried out.”

Detroit retirees and supporters protest at Crain’s Detroit luncheon honoring Bankruptcy Judge Steven Rhodes and Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr, on Feb. 25, 2015.

U.S. District Court Judge Bernard Friedman earlier denied all five appeals, based largely on a judicial doctrine known as “equitable mootness.” In layman’s terms, that means, “We’ve done it, it can’t be changed because that would cause financial chaos, and it’s too late to for you to do anything about it.”

The retirees in the five appeals do not agree. They argue that the bankruptcy plan should be considered on constitutional grounds by a higher court, and that it can be altered to exclude cuts to retirees by remanding it back to the bankruptcy court to make it comply with state constitution language protecting public pensions. DAREA argued in its brief that even PA 436 compels emergency managers to honor that the pension protection clause.

DAREA said in its brief, “A total of $5.5 billion, or 78 percent of the total bankruptcy relief, comes off the backs of city retirees.” Later it added, “The City of Detroit may have to find some alternative funds to make up the difference in the funding necessary to restore pensioners to their full payments. But that funding will be relatively small and can be provided without disrupting the plan of adjustment. The city can seek alternative sources of funding for blight removal. As has been done in cities, states and the federal government, the City of Detroit could go after the major banks, whose predatory lending policies led to the destruction of neighborhoods throughout Detroit, to fund blight removal, rather than taking funds out of the general fund.”

DAREA said in its brief, “A total of $5.5 billion, or 78 percent of the total bankruptcy relief, comes off the backs of city retirees.” Later it added, “The City of Detroit may have to find some alternative funds to make up the difference in the funding necessary to restore pensioners to their full payments. But that funding will be relatively small and can be provided without disrupting the plan of adjustment. The city can seek alternative sources of funding for blight removal. As has been done in cities, states and the federal government, the City of Detroit could go after the major banks, whose predatory lending policies led to the destruction of neighborhoods throughout Detroit, to fund blight removal, rather than taking funds out of the general fund.”

The court heard oral arguments on only three cases, those brought by actual attorneys, Jamie Fields on behalf of the Ochadleus appellants, John Quinn, and Dennis Taubitz. But it is reviewing all five appellant briefs before it issues its ruling. (See links to briefs below.)

Jamie Fields speaks about 6th Circuit appeals of bankruptcy at DAREA meeting.

Fields, whose group largely represents police and fire retirees, said in part, “The District Court’s finding of equitable mootness . . . .allows the bankruptcy court to exercise final judicial power that it cannot constitutionally wield. . . . The bankruptcy court did not have the constitutional authority to issue a final, non-appealable ruling on what Art. 9 Sec. 24 of the Michigan Constitution meant.”

Sec. 24 says, “The accrued financial benefits of each pension plan and retirement system of the state and its political subdivisions shall be a contractual obligation thereof which shall not be diminished or impaired thereby.”

In supplemental briefs, both Fields and DAREA cited an Illinois Supreme Court ruling rejecting cuts to Illinois state employees based on almost identical language in that state’s constitution.

“The people of Illinois give voice to their sovereign authority through the Illinois Constitution,” Illinois Justice Lloyd Kormeier wrote for that court. . . . “the Illinois Constitution . . . expressly provides that the benefits of membership in a public retirement system ‘shall not be diminished or impaired.’”

Fields added, “Our argument is that Annuity Savings Fund (ASF) matter had no business in bankruptcy court period; it is not related to the bankruptcy at all.”

Public workers demonstrate as Illinois Supreme Court decides on pension cuts in 2015. It said they could not be cut, based on Illinois State Constitution protections.

Attorney John Quinn argued likewise regarding the ASF, which comprised the major part of his appeal. Both said the city had never even filed a “proof of claim” with regard to ASF cuts.

Detroit retirees who participated in the voluntary ASF plan put either 3, 5, 0r 7 percent of their paychecks into the ASF, in addition to their pension contributions, with no matching funds from the city. Those who retired in 2003 and afterwards were hit with huge cuts to their accumulated annuities under the bankruptcy, in addition to a 4.5 percent cut to their pensions and loss of health care benefits.

The city contended the ASF’s paid a set 7.9 percent rate of return even in years when the pension funds had lower returns. They cited as particular examples the years of 2008 and 2009, during which rates of return dropped drastically due to the global economic crash caused by Wall Street’s predatory lending practices.

DAREA protested with opponents of tax foreclosures in Detroit June 8, 2015.

Fields said that the bankruptcy court may have had authority to hear concerns about employees’ pensions, but its decision on those matters those would still be appealable under two landmark Supreme Court decisions, Stern v. Marshall, and Wellness International Network, Ltd., et al. v. Sharif. The second decision said bankruptcy courts could make final decisions on major matters, but only if both parties, creditor and debtor, agreed.

“If you take away [higher court] review on the merits . . .you are taking away the [limited] jurisdiction or authority the Congress gave the bankruptcy courts, . . .making equitable mootness a per se rule,” Fields said.

Attorney John Quinn argued likewise regarding the ASF, which comprised the major part of his appeal. Both he and Fields said the city had never even filed a “proof of claim” with regard to the ASF cuts.

Below is video explaining difference between Article I and Article III Courts. In USSC Stern v. Marshall, 564 U.S. 462 (2011), the Court held that a bankruptcy court, as a non-Article III court (i.e. courts without full judicial independence) lacked constitutional authority under Article III of the United States Constitution to enter a final judgment on a state law counterclaim that is not resolved in the process of ruling on a creditor’s proof of claim.

Quinn pointed out, “The court is well aware that this is very important case. This is the largest municipal bankruptcy in history, and will have a major impact on the development of Chapter 9 law for some time to come. It is imperative that the issues involved be considered by an Article III court.”

Article III Courts are federal courts given full judicial authority under the U.S. Constitution, while bankruptcy courts are Article I courts, at the lowest level, and are given only limited authority.

One of many protests which took place during Detroit bankruptcy proceedings.

Quinn said, “Section1123A4 of the Bankruptcy Code requires that you get the same treatment in terms of percentages of all creditors in a particular class. The ASF recoupment applies only to some creditors in Class 11. The majority [of retirees] are getting only a 4.5 percent pension cut, but people subject to ASF recoupment are getting a 20 percent cut.”

He argued that nobody should have the 20 percent cut unless they agreed to it individually or the Detroit General Retirement System successfully litigated a claim against its members.

Marc Swanson of Miller, Canfield and Smith

Arguing for the City of Detroit was Attorney Marc N. Swanson of the firm Miller, Canfield, Paddock and Stone, which played a large role in getting Detroit under emergency management, although the Jones Day law firm was viewed as the major actor in the bankruptcy case.

“This is a textbook case for the application of the doctrine of equitable mootness,” Swanson said. “No stay was obtained no stay was diligently pursued. This plan has been substantially consummated. The relief requested will cost the city $816 million in outside funding [A/K/A “The Grand Bargain}, burden the city with more than $3 billion in additional debt and plunge the city back into financial chaos, devastating its residents and returning them to an “inhumane and intolerable” situation as Judge Rhodes found.”

Sixth Circuit Judge Karen Nelson Moore conducted extensive questioning of Swanson with regard to the issue of “equitable mootness” and whether the appellants would have had to ask either the District Court or the Sixth Circuit to stay implementation of the Eighth Amended Plan of Adjustment.

“This assumes the doctrine of equitable mootness applies to Chapter 9 bankruptcies,” Moore said. “The cases in which this court has adopted equitable mootness are all Chapter 11. Don’t we have to have some kind of statutory basis or are you saying this is completely a judicial doctrine with no mooring in the bankruptcy statutes?”

DAREA members sign first bankruptcy appeal in Jan. 2015.

Swanson claimed that there is no statutory basis for equitable mootness in either Chapter 7, Chapter 9, or Chapter 11 cases, and therefore it is a matter of judicial decision. However, Moore countered by citing two statutes in the bankruptcy code that apply to Chapters 7 and 11.

She also noted, “Given the Supreme Court’s recent decisions that are telling courts don’t refuse to exercise their jurisdictions, shouldn’t we examine carefully the doctrine of equitable mootness in Chapter 9 when we don’t have any Sixth Circuit chapter 9 cases?”

Judge McKeague asked Swanson, “Why would equitable mootness apply to Chapter 9 cases if the bankruptcy court is not authorized to order the sale of city assets?”

McKeague thereby touched on a prime difference between Chapter 9 and the other bankruptcy chapters.

The Great Lakes Water Authority, an unelected regional body, took over the revenue and most assets of the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department under the Detroit bankruptcy decision, despite City Charter guarantees that a vote of the people was required.

According to a summary of Chapter 9 on the U.S. Supreme Court website, Section 904 of the Bankruptcy Code limits the power of the bankruptcy court to “interfere with – (1) any of the political or governmental powers of the debtor; (2) any of the property or revenues of the debtor; or (3) the debtor’s use or enjoyment of any income-producing property” unless the debtor consents or the plan so provides. . . In addition, the court . . . cannot convert the case to a liquidation proceeding.”

In the case of the Detroit bankruptcy, Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr authorized the sale, (misnamed a “lease”) of virtually all of Detroit’s assets, including the revenues of the $6 billion Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to the Great Lakes Water Authority, and the conversion of the multi-billion dollar Detroit Institute of Arts collection to a bank trust no longer under control of the Detroit City Council.

Moore and McKeague also questioned Swanson’s insistence that the appellants must have requested a “stay” of implementation of the bankruptcy plan in order to prevail.

Detroit bankruptcy protest

“Another problem is that doctrine of equitable mootness means that there is no Article III court that ever considers any of these issues, that it is entirely up to an Art I bankruptcy court to decide how a city’s bankruptcy should be resolved,” Moore said.

Swanson countered that “the appellants contributed to that. They chose not to pursue a stay in the District Court, or in this court, chose not to ask the court for an expedited hearing, or request an interlocutory review of the bankruptcy court’s denial.”

McKeague countered, “[Attorney] Fields says it doesn’t matter whether stay pursued—it’s whether it was done.”

Swanson again stressed the problems with rewinding the Plan of Confirmation, saying, “Granting the appellants’ demands would leave city without a viable plan and force the dismissal of the case. The city would have to clawback $50 million in cash, $910 million in bonds to creditors, refund $220 million to the to the state, and somehow reverse its irrevocable transfer of the art collection to a charitable trust. It would again face race to the court lawsuits and crushing debt.”

Many bankruptcy opponents demanded complete cancellation of Detroit’s debt to the banks, blaming them for the city’s crisis.

Moore countered, “The points you’ve raised are very serious. They would guide an Article III court in equity in deciding what the appropriate remedy for appellants’ asserted wrong would be. There are serious factors about the amount of things that have happened already.”

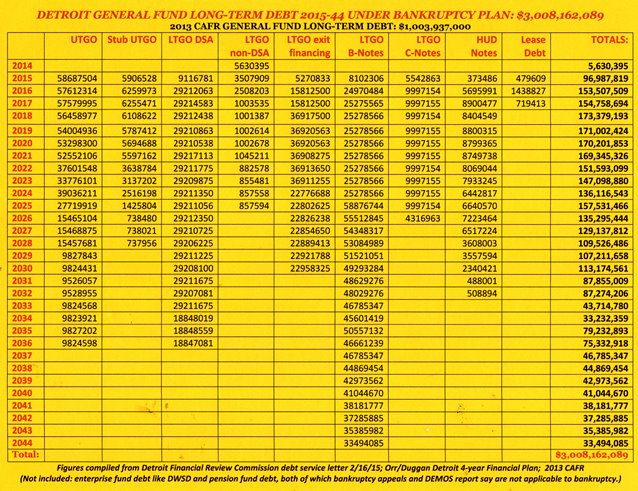

With regard to Detroit’s “crushing burden of debt,” VOD earlier published an analysis of the city’s debt pre and post-bankruptcy, which found that Detroit’s outstanding debt is now 300 percent greater than it was before the bankruptcy, largely due to the issuance of new bonds to pay off its corporate creditors.

VOD wrote on March 1, 2015, “The Detroit Financial Review Commission (DFRC) published figures Feb. 16 that show the city’s total general fund long-term debt (LTD) from 2015-44 is now $3,008,162,089. According to the city’s last available Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) of 2013, the general fund LTD then was $1,003,937,000.”

The Detroit Active and Retired Employees Association’s next general membership meeting is Wed. July 6, 2016, at 5:30 p.m., St. Matthews and St. Josephs Church, Woodward at Holbrook.

FUNDRAISING: To donate to DAREA’s LEGAL DEFENSE FUND, click on http://www.gofundme.com/pensiondefensefund. Or checks can be made payable to the Detroit Active and Retired Employees Association (DAREA), at P.O. Box 3724, Highland Park, Michigan 48203.

“Hands off my Pension” T-shirts are available for $10 each. DAREA baseball caps are available for $25 each. The fundraising committee will continue to sponsor events to cover legal fees and other meetings. DAREA has pledged to go all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court if necessary.

WEEKLY MEETINGS: To receive notices of meetings, updates on the appeal and events information please provide your email address and phone numbers via email at Detroit2700plus@gmail.com or call DAREA at 313-649-7018.

DAREA general membership meeting.

Related Documents:

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/Demos-Detroit-bankruptcy-report-highlighted-1.pdf

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/DAREA-Sixth-Circuit-Appeal-brief-12-28-2015-1.pdf

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/Fields-Sixth-Circuit-appeal-brief.pdf

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/Quinn-brief-6th-Circuit.pdf

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/Taubitz-Industrious-6th-Circuit-brief.pdf

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/Darrah-brief-6th-Circuit.pdf

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/Pontiac-retirees-health-care-6th-Circuit.pdf

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/Phillips-et-al-renewal-brief-2016.pdf

Related stories:

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2015/02/18/a-tale-of-two-elections-in-michigan-its-all-black-and-white/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2014/12/14/leaving-bankruptcy-detroit-takes-on-1-28-billion-of-new-debt/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2014/10/21/why-the-poor-are-paying-for-detroits-bankruptcy/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2014/09/06/racist-bankruptcy-plan-hearing-sanctions-theft-of-detroit/

Related from other sources:

http://www.publicsectorinc.org/2014/02/detroit-pension-borrowings-what-a-tangled-web/