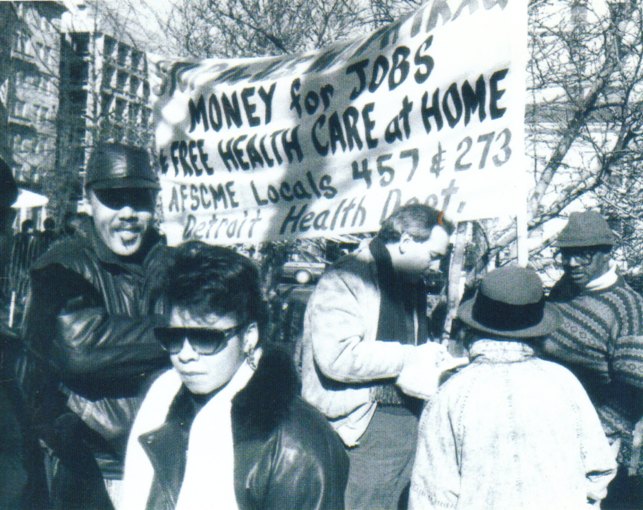

Al Phillips, President of AFSCME Local 457, at right, talks to reporter during Health Department locals 457 and 273’s participation in national march against the first war on Iraq in 1991.

BATTLE TO MAINTAIN PUBLIC HEALTH CARE TOOK THE LIVES OF MANY UNION OFFICIALS FROM DETROIT GENERAL HOSPITAL, HEALTH DEPT.

By Diane Bukowski

May 19, 2012

DETROIT — Detroit Department of Health and Wellness Promotion Director Loretta V. Davis told VOD to email her so she could send documents allegedly proving the state established Detroit’s health department in 1978, as she contended at the City Council hearing May 16.. She said they were part of the Michigan Public Health Code, but could not cite a section. To date she has not responded to VOD’s email, sent the same day as the hearing.

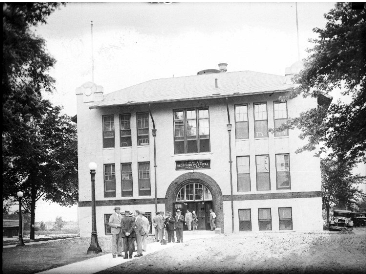

Detroit Receiving Hospital, later renamed Detroit General Hospital, circa 1933; in 1949 Detroiters voted to put it under the control of the Detroit Health Department.

In fact, Detroit’s Health Department has had a long and prominent history as an independent city-operated entity since 1825. The Common Council, as it was then known, appointed three doctors to look after the health of the city’s poor residents in 1827, according to an article in the July, 1955 issue of the American Journal of Public Health.

The article’s authors, Joseph G. Molner, M.D., MPH, and Vlado A. Getting, M.D., Dr. PH, mention no state government role in their article at all. According to the 1918 City Charter, Detroit’s Mayor appointed the four member Board of Health, which operated the Health Department. (Click on Detroit Health Department history for full article.)

The authors detail the founding of Detroit Receiving Hospital in 1913, and its subsequent transfer to the Detroit Health Department in 1949.

“In 1913 the city determined it would furnish more hospital space for its sick poor and under the Board of Poor Commissioners constructed the first unit of the Detroit Receiving Hospital. The City Physician’s Office became attached to the Receiving Hospital. In 1948 the Welfare Department, which operated the Receiving Hospital, was severely criticized and as a result of the vote of the citizens the 538-bed Receiving Hospital, its branch, the Redford Receiving Hospital, containing a 48-bed emergency unit, and the City Physician’s Office were transferred to the Health Department. Since 1949, therefore, all city operated medical hospital facilities in Detroit have been administered by the Health Department.”

Entrance to Maybury Sanitorium; many have questioned its role in randomly interning poor Blacks in Detroit as suspected TB carriers.

Redford Receiving Hospital. Photo Sept. 1929

By 1953, the article’s authors say, the Department operated Receiving Hospital, Herman Keifer Hospital, Maybury Sanitorium (for tuberculosis patients), a Redford Emergency Branch, the City Physician’s Service which provided 36,007 home visits that year, five district health centers which provided well-child care among other services, school dental clinics, and the Central Office X-Ray Clinic. (See photos at left.)

Health and Hospitals were divided into two departments under the City Charter of 1974, the year Detroit’s first Black Mayor, Coleman A. Young, took office. Detroit Receiving Hospital was by then known as Detroit General Hospital. Eventually, many Black doctors, nurses and other workers were employed at DGH, the Health Department, and other city departments.

This reporter began 20 years of work at the Detroit Health Department in 1974.

She was first at Gratiot Health Center (now demolished), next at Bruce Douglas Health Center, (then at 6500 McGraw, now privatized under the Detroit Community Health Connection) and then at Herman Kiefer Health Complex in the community nursing division (which employed Vernice Davis Anthony and Jean Chabut) and the TB clinic (both divisions now defunct).

She was an elected official of AFSCME Local 457 for most of that time.

This reporter now takes up the history of the Health Department subsequent to 1974 from her own knowledge. At that time, Local 457 represented workers at bot

h the Health Department on Taylor and Detroit General Hospital on St. Antoine in downtown Detroit. The Local had over 1200 members.

In 1976, a drive to turn Detroit General Hospital over to the private, then non-profit Detroit Medical Center began. Detroit was the first major city to be hit with such a proposal. Many other large cities including New York and Chicago still have their public hospitals and health departments, despite cutbacks.

From 1977-1980, Local 457 President Hazel Edwards led a city-wide campaign to “Save Detroit General Hospital,” which included a coalition with UAW Local 3, representing Dodge Main plant workers. The corporate drive to shut Detroit’s auto plants in the wake of militant organizing by their Black workers had also begun.

Hazel Edwards, President AFSCME Local 457

Dodge Main workers joined DGH workers to save their city

Organizers warned that if Detroit General Hospital was privatized, and Dodge Main shut down, a wave of privatization and plant closings would end up destroying Detroit, since jobs for public employees and auto workers were the mainstay of the economy. They also presented the first real opportunity for Black Detroiters to have unionized jobs with decent wages and benefits.

Everything that was then predicted has since come to pass.

As part of the campaign, The Concerned Citizens for Detroit General Hospital, also headed by President Edwards, undertook a massive petition drive to have the people of Detroit vote on whether their only remaining public hospital should be privatized. Tens of thousands of signatures were gathered and turned in to then City Clerk James Bradley, enough to put the question on the ballot.

The late Erma Henderson, Pres. Detroit City Council

However, a court later ruled that “budgetary matters” could not be put on the ballot. A footnote to that effect continues in the current City Charter.

Detroit’s City Council had the final say-so on the privatization of DGH. After a night-long sit-in in City Council chambers, during which DGH workers and others were arrested, the Council voted for the move. Only then Council President Erma Henderson and Council Member Ken Cockrel, SENIOR voted NO.

When the DMC took DGH over, it busted the union. It was four years before AFSCME Council 25 was able to organize workers there again, at lower wages and benefits. President Edwards, a beautiful and brilliant union leader and negotiator, suffered a stroke in 1981 and was severely disabled from then until her death in a nursing home in 1993.

Her successor at Local 457, Dorothy Worthy, died of cancer as she neglected her doctor’s appointments while the Local continued to fight ongoing privatization at the Health Department itself. Private agencies including the Southeast Michigan Health Association (SEMHA), and substance abuse programs set up shop in the city-owned Herman Kiefer Health Complex, city jobs were contracted to private workers with no pensions attached, and the Department became a shell of its former self.

Worthy was succeeded by Anita Hicks, who led a campaign to organize Community Nutrition Workers, whose privately contracted jobs were previously those of Community Health Assistants. Acting Director George Gaines fired all the CNW’s, but their jobs were later won back after militant protests outside Herman Kiefer.

Local 457 union officials Helen Webb, Alvin Jones, Diane Bukowski and Laurie Walker in 1993; even then the Local was raising the demand to make the banks and corporations pay; Photo by Local 457 President Al Phillips

Local 457 President Al Phillips succeeded Hicks, taking on an uphill battle to stop the erosion of city workers’ jobs and rights. He was a co-founder of the Detroit Coalition to Stop Privatization and Save Our city in 1992, which united all 17 city locals and the community in a battle for Detroit. During its candidate hearings, the Coalition got promises from nearly all the mayoral and council candidates that they would not privatize city services and jobs.

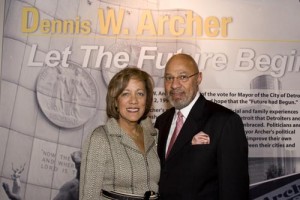

Detroit Mayor Dennis Archer with wife Judge Trudy Duncombe Archer, anticipating a future of privatization.

AFSCME Council 25 endorsed Mayor Dennis Archer based in part on those promises. But after months spent following up on Archer’s promises in the Health Department, meeting with City Council, Labor Relations, the Health Department Director, and others to demand the return of city jobs and services there, President Phillips died of a massive heart attack on April 16, 1994.

It later turned out that Archer, who spoke at Phillips’ funeral, was already in the process of transferring control of the Department’s health clinics to private agencies, among other actions.

As the proposal for the Institute for Population Health shows, the problem with health services in Detroit is not control by the city of Detroit, which now spends little on those services.

Since the privatization of Detroit General Hospital, now called Detroit Receiving under the for-profit DMC owned by Vanguard and a Wall Street hedge fund, the problem has always been the insatiable greed of the private corporations, insurance companies, and banks to maximize their profits on the back of the poor. Public health and hospitals, which are a human right, should be owned and run by the people and their elected representatives, not for profit.

I am looking for a photo of Redford Receiving Hospital. It was our neighborhood hospital. Any idea where I can access a picture? Thanks.

Hello Ms. Borchert, 8 years after your comment. The story on the history of the Detroit Health Department on Voice of Detroit has now been updated to include a photo of Redford Receiving Hospital at

https://voiceofdetroit.net/2012/05/21/detroit-founded-health-dept-in-1825-it-previously-ran-3-hospitals-including-detroit-general-5-clinics-physician-home-visit-services/

Dear Ms. Bukowski and VOD,

I found this article to be a fascinating read for several reasons. I am a native Detroiter. My mother and many others worked at Detroit Receiving.

I witnessed neighbors, who became involved with drugs and homeless, huddle around the steam grates, in the wintertime, trying to keep warm…

I have a clear recollection of the hospital, at a time when it was located across from the current site of the Frank Murphy Hall of Justice (formerly Detroit Recorder´s Court). Moreover, I also spent a great deal of time in and out of there owing to asthma during my childhood.

One of my sisters was briefly hospitalized at Herman Kiefer in connection with a minor matter, but my father boldly took her out of there and brought her home, over the objections of the doctors and security personnel, because he feared that the could contract TB.

Finally, I am sensitive to the political context of the issues raised in this article and one in yesterday´s news, concerning a hotly contested lawsuit challenging the “transfer and privatization” of the City´s Health Dept!

The pictures brought tears to my eyes. Thanks.

Respectfully submitted,

Lovester Wilson