By Glenn E. Morgan Jr

“Soldiers are made by other Men;

Warriors are born by God given Birthright”

–Aasiyaku Bisseau X. (pseudonym)

October 11, 2012

The mass incarceration of black men and other men-of-color in U.S.prisons warrants national and international attention as a human rights issue. A number of studies shed light of this complex and important problem.

The study titled The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarcerations in the Age of Colorblindness by attorney Michelle Alexander illuminates this pressing issue. She candidly states that the system of mass incarceration functions as a “well-disguised method of racialized social control” reminiscent of the old American South’s Jim Crow system.

This has certainly led to the increasing number of men-of-color, particularly black men, in U.S. prisons. It is obvious that the criminal justice system—which is ‘criminal’ itself—operates like a conveyor belt system in a factory. It criminalizes you. Then takes you through the legal process. Imprisons, rehabilitates, and then back into society you go.

Well, that’s the idea, or should I say formula.

I know—I have been through it at the federal level. Let me give you the abbreviated version of my story if you (as the reader) are not familiar with it.

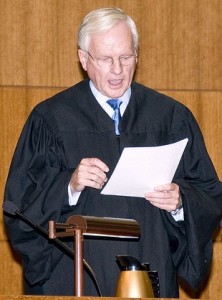

On February 16, 2012, I was sentenced to do ninety days in a federal facility by ring-wing, ultra-conservative U.S. 6th District Circuit Court Judge Robert H. Cleland who was appointed by President George Bush in 1990.

Next, the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) notified me six weeks or so later that the Federal Correctional Institution(FCI) in Milan, Michigan forty miles south of Detroit would be the facility for my incarceration. I was to “self-surrender” at the facility onMay 15, 2012.

On May 15, 2012, I reported to the FCI-Milan. I said my goodbyes, went through the official intake formalities, and walk through the sprawling three-hundred acre facility’s gates to serve my ninety days.

I did not know what to expect before going to FCI-Milan. I am not, nor ever have been, a “career criminal” who knows the ins and outs of prison life and system.

Once inside, I immediately recognized the ethnic/ racial breakdown not long after being mainstreamed into the general inmate population, which range from 1200 to 1500 respectively (estimated). Black males made up the majority of the inmate population, followed by Hispanic males (non-black), white males, and Others (i.e. Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, etc.). FCI-Milan’s inmate demographic did not surprise me because it mirrored the plethora of studies out there about the mass incarceration of men-of-color.

Narcotics and white-collar crimes are the primary offenses committed by the “captives”—as I called them—at FCI-Milan. A lot of black men are serving short and long term sentences for drug convictions: 5- to-10 years on up. Clearly, a result of the quote “War on Drugs” as Alexander points out in her book.

I was a little dismayed to find out that many of them are from the City of Detroit; I found this out from “Brothers” from the city who had been at FCI-Milan for years and knew the ropes as far as who’s in for what offense.

I used the moments when Brothers from the city who asked me about my case to find out information about their experiences with the criminal justice system and how they felt about their drug conviction, or whatever the offense might be. The overwhelming consensus was that the “black man can’t get a fair shake under the whites man’s unjust legal system.” And, that “the drug laws, and laws in general, in this country are biased.” No surprise at all.

Some said that my sentence was unjust and that I was being made an example of because I am black despite the fact that the so-called “victim” was also black. An elder black gentleman insisted that if I was white the judge—whom some called Ku Klux Kleland—would have given me probation, home confinement, sent me to a halfway house, or a federal camp as my punishment. I told anyone who would ask me that I considered myself a “political prisoner.” And, that there was a purpose—outside of the sentence I received—for me being at FCI-Milan.

The stories these men told me about their experiences as black men with the “system” made me think of author Richard Wright’s classic novel Native Son and its main character Bigger Thomas, a menacing “N—-r” brute by white society’s standards. Thomas (accidentally) murders a white woman out of built-up frustration and rage with the white world he exists in within the novel. Wright ends the novel with Bigger Thomas being imprisoned and unjustly sentenced to death The moral of the novel is that black men must know there place in a white society and function within its racist social conventions.

In a way, a lot of the Brothers have been given death sentences, not physically but emotionally, mentally, and spiritually at FCI-Milan. I could see it in their faces as they told me their stories.

So, three weeks into my sentence—after absorbing the stories and prison culture emotionally, mentally and spiritually myself—I developed the Men of Afrikan Descent (M.O.A.D) Project, a quasi-ethnographic study of sorts, inspired by Alexander’s book and others on the issue of mass incarceration.

I figured here I am a 41-year-old highly, maybe, overeducated black man with the opportunity to put a face and voice on the system of mass incarceration. I went into researcher mode but in a stealth fashion. I further conversed, interacted, chronicled, listened and observed while “handling my business” in street terms.

I specifically targeted the Native Sons from the city who ranged in age from their early 20s to their late 60s. Generations of black men with different and similar beliefs, ideas, experiences, habits, opinions, values, and tastes with connections to the city and the community. Most of us lived in the city all of our lives. There was a common love for family, community, and the city that “we” shared as black men.

But, I found myself with mixed feelings when it came the my “313” Brothers incarcerated for “gang-bangin” and/ or being in the “dope game” that continues to devastate the city and its majority black community.

As a Native Son myself, I relate to the allure of the dope-game and the city’s street culture. I relate to the vicious cycle of violence that plagues the city. At the age of ten, I witnessed a man brutally killed in front of me on the city’s Westside: an image forever emblazed in my psyche. I have always felt my innocence was stolen at that moment like some young people who witness violent acts in the city might feel today.

It is no secret that a lot of the social pathology in the city’s black community comes at the hands of black men. Some black males incarcerated or on the streets are of no benefit to the community or our people, an opinion I expressed in civil debates with other black men at FCI-Milan. A bitter pill to swallow but true.

But, I am relieved to report that a lot of Detroit Brothers demonstrated a commitment to improve themselves by acquiring new educational, job, life, and social skills to “re-enter the community. During a few personal conversations, some Brothers were remorseful for any role they may have played in causing chaos in the community.

However, a few expressed concern about returning to the real world out of fear they would return to their criminal ways, especially if no resources are available to get financial assistance, jobs, housing, etc. According to the Sentencing Project 2012 report, the recidivism rate is much higher for repeat ex-offenders who lack access to resources to sustain themselves.

Detroit’s black community must counter the insidious system of mass incarceration by advocating for resources, and lobbying lawmakers for changes in public policies when its comes to the criminal justice system. These actions help to create a safety net for the Brothers who are coming home. Before leaving FCI-Milan, I made a promise to others and myself to become a louder voice in chorus with others.

On Monday, August 13, 2012 at 7:30 a.m., I walked to FCI-Milan’s Discharge and Receiving Unit to prepare for release. The morning was busy as usual. A “move”—which allows inmates to go from place to place in the facility—was announced over the blaring inter-com system. I took my last look at the sea of faces as they flurried through the facility’s courtyard.

A guard escorted me down a long corridor to the holding area to change into my civilian clothes. Several male inmates—black, Latino, white—who work in the unit “oddly” congratulated me on going home and wished me well.

Soon thereafter, the clank and rattle of bars and chains echoed in my ears. Eight men—all black—were being herded into a cell before their intake process began. A potpourri of thoughts ran through my mind while watching these Brothers being corralled together like savage animals.

For a second, I had an Attica moment but instead clutched my fist, gave the Brothers the peace sign, and made my way back into the real world. In the rap lyrics of hip-hop legend Nas: “If I ruled the world, I’d free all my Sons…Just imagine that. If I ruled the world.”

Yet, the reality is that black men, and other men-of-color, exist in a society that still sees them as public enemy number one.

Glenn E. Morgan Jr. is an activist, entrepreneur, journalist, and writer. The Native Detroiter is working on his memoir titled Confessions of a Native Detroiter: Why Bad Black Boyz In the ‘D’ Don’t Cry. Contact him at http://www.facebook.com/glennjr1971, or glenn_morgan_71@hotmail.com