Pushback with Aaron Maté

Pushback with Aaron Maté

Ukrainegate impeachment saga worsens US-Russia Cold War

As the House opens impeachment hearings for President Trump, Professor Stephen F. Cohen (above) warns that the US military assistance at the heart of Ukrainegate escalates the US-Russia Cold War.

As the House opens impeachment hearings for President Trump, Professor Stephen F. Cohen (above) warns that the US military assistance at the heart of Ukrainegate escalates the US-Russia Cold War.

Guest: Stephen F. Cohen, professor emeritus of Russian studies at New York University and Princeton University, contributing editor at The Nation, and author of War with Russia: From Putin & Ukraine to Trump & Russiagate.

TRANSCRIPT

AARON MATÉ: Welcome to Pushback. I’m Aaron Maté, here with Stephen F. Cohen, professor emeritus of Russian Studies at Princeton and NYU, author of the book, War With Russia?, question mark, From Putin & Ukraine to Trump & Russiagate. Welcome, Professor Cohen.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: Good to be with you again. Thank you.

AARON MATÉ: So, let’s talk Ukrainegate, dominating the news right now. At the center of this impeachment drive against Trump is that he briefly froze military aid to Ukraine and the belief there is he did so for political purposes. Putting that question aside, what has gotten lost in all this is the question of why are we sending military aid to Ukraine, and is that wise policy? The conventional line we get is that we are helping defend Ukraine from Russian aggression after Russia invaded Ukraine, took Crimea illegally in 2014, and we are helping Ukraine respond to that and to help support Ukraine in its fight against Russian separatists in the Donbass. What say you to that?

Pres. Barack Obama

U.S. Pres. Donald Trump

STEPHEN F. COHEN: Well, the first thing to remember is, is that President Obama was under enormous pressure to send military equipment to Ukraine. I don’t know if you remember that or not, but it was a major campaign and it was led, as I recall, by people very close to him, and he refused. And why did he refuse? Well, I’m not sure what his calculation was, but the, the wisdom of not sending is clear.

First of all, what everybody must want is peace between Russia and Ukraine. So why would you pour more weapons, why would you tempt one Ukrainian—now the leadership of Ukraine has changed—but why would you tempt one or another Ukrainian leadership to broaden the war, where you want above all to bring peace? Correct? Secondly, in whose hands eventually do such weapons fall? I mean, there’s no guarantee in a place like Ukraine, that the Ukrainian army, which is involved in the black market in a big way, those weapons could go anywhere.

But ultimately you have a situation now which seems not to be widely understood, that the new president of Ukraine, Zelensky, ran as a peace candidate. This is a bit of a stretch and maybe it doesn’t mean a whole lot to your generation, but he ran a kind of George McGovern campaign. The difference was McGovern got wiped out and Zelensky won by, I think, 71, 72 percent. He won an enormous mandate to make peace.

Vlodomyr Zelensky

Vladimir Putin

So, that means he has to negotiate with Vladimir Putin. And there are various formats, right? There’s a so-called Minsk format which involves the German and the French; there’s a bilateral directly with Putin. But his willingness—and this is what’s important and not well reported here—his willingness to deal directly with Putin, which his predecessor, Poroshenko, was not or couldn’t or whatever reason—actually required considerable boldness on Zelensky[‘s part], because there are opponents of this in Ukraine and they are armed. Some people say they’re fascists but they’re certainly ultra-nationalist, and they have said that they will remove and kill Zelensky if he continues along this line of negotiating with Putin.

So now along comes Trump, right? So, Trump makes a wrongheaded phone call to Zelensky, about Biden and information. It was the wrong thing to do, no two ways of looking at that. But the more important thing is, and that’s why I’d like to see the full transcript of the…we’ve only been given a partial so far as I know. I want to know if Trump encouraged Zelensky to continue the negotiation with Putin, and here’s why. Zelensky cannot go forward as I’ve explained. I mean, his life is being threatened literally by a quasi-fascist movement in Ukraine, he can’t go forward with full peace negotiations with Russia, with Putin, unless America has his back. Maybe that won’t be enough, but unless the White House encourages this diplomacy, Zelensky has no chance of negotiating an end to the war, so the stakes are enormously high.

Why are U.S. weapons going to Ukraine?

All this stuff about Biden, it’s bad but it’s a distraction. It’s not what we should be focusing on. We should not be shipping more weapons there. What we should be doing, and certainly what, given Trump’s inclination to be a dealmaker and like a semi-peace candidate—but you wonder if there’s anybody around him to explain these things to him—but this is an opportunity for Trump to do the right thing and do it clean, to say to Zelensky, “I support this negotiation with Putin. I hope that you and Putin can settle your conflicts.” If the Germans and the French, because there was this so-called Minsk format that involved them, need to be brought in, okay, but Europe’s pretty much lost interest in this and there’s no leader.

I mean, what makes the moment interesting, stop and think about it a minute, Aaron, is there’s no kind of—what’s the right word?—there’s no transformative or decisive type of leadership in Europe. I mean, because these countries have their own leader[s]. Merkel’s on her way out. We don’t know what will be the next leader. Boris Johnson is, well, Boris Johnson. Macron is attempting to fill the role. He wants to be the leader of the West in a relationship with Russia. He’s trying to…it’s very interesting what he’s doing because he’s trying to replicate what de Gaulle did. De Gaulle wanted France to be the diplomatic bridge between east and west. Let him try, but there’s, there’s a moment, I mean, I, all my life I, I have a book called Lost Opportunities, Soviet Alternatives and Lost Opportunities [Soviet Fates and Lost Alternatives]. There’s, there were moments in history, political history, when there’s an opportunity that is so good and wise and so often lost, the chance. So, the chance for Zelensky, the new president who had this very large victory, 70 plus percent to negotiate with Russia an end to that war, it’s got to be seized. And it requires the United States, basically, simply saying to Zelensky, “Go for it, we’ve got your back.”

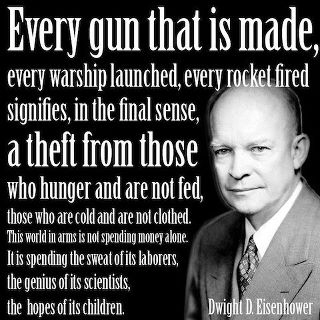

The “military-industrial complex,” a term coined by former U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower.

AARON MATÉ: Well, let’s talk about the forces in Washington that do not share that point of view, that do not want to encourage a peace process between Russia and Ukraine. You know, you mentioned Trump, when Trump met with Zelensky, Trump did say that he encourages Zelensky to make a deal with Putin and he thinks that would be a good thing. But that is not an opinion shared in, in Washington.

Talk about the people who in DC, who helped bring us this crisis to begin with, the same ones who were pressuring Obama to send a lethal aid…

STEPHEN F. COHEN: Let me sit in your chair a moment. I mean, just theoretically, what could…what imaginable reason could anybody in Washington have for not wanting to see peace between Ukraine and Russia?

AARON MATÉ: You know, I have my theories. The influence of the military-industrial complex. It’s profitable to have tensions with Russia. There was an attempt in Ukraine, obviously, you know, at, with the Maidan crisis, the, which began all this, to wrestle…

STEPHEN F. COHEN: In 2013, 2014.

AARON MATÉ: Yeah, which is when the US helped—including Joe Biden—helped back an ouster of a corrupt but democratically elected president, Yanukovych.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: So, let’s stop there. I mean, we are obliged to use this formula, “corrupt but democratically elected.”

AARON MATÉ: It’s true.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: Well, yes and no. But there…which is more important? That he…I don’t even know what it means that he was corrupt. I mean, he siphoned off a lot of state money for himself…

AARON MATÉ: He’s corrupt.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: This is culture.

AARON MATÉ: Okay.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: This is a culture. I mean, the point here is, is that we, since the end of the Soviet Union, have said that we want to promote democracy and particularly constitutionalism, right? As opposed to political caprice in the former Soviet territories. You agree, that’s been official American policy. Why then would you, you, you depose…support the overthrow by a street mob—whatever you call it, I don’t care what democratic banners they were carrying because there were plenty of neo-fascists among them, too—who had been a leader, who had been by all ratifying European monitoring organizations freely and fairly elected? It had been a fairly clean election, especially when he had already agreed to move elections up. I think within nine months you could vote him out.

The US –including Joe Biden—helped back an ouster of democratically elected president, Yanukovych, who called the effort a “coup.”

Why would the United States, therefore, immediately, within hours, this being President Obama, support was for essentially a street coup? I mean, it’s a blow to constitutionalism, the very cause that we claimed to be promoting, so we need to think about that. That was a turning point. It sent a message about what the United States really was prepared to send. I mean, that’s a little digression on my part, but it was a very important moment—and it was very wrongheaded.

AARON MATÉ: It was. You had John McCain and Victoria Nuland visiting Ukraine, Nuland passing out cookies to protesters. We can imagine if, say, Russians went to Mexico City, helped back a coup there and changed the government, and then talked about having Mexico City join a military alliance with Russia, which was the talk about Ukraine joining NATO.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: I fully agree, but I just keep coming back in my mind and replaying these events, that this idea that maybe democracy and constitutionalism could take root in these areas that really hadn’t had much of it, right? And this is a pivotal moment because Yanukovych, then the president, had by all counts been freely and fairly and constitutionally elected. Mind you, he had also signed an agreement brokered by the, I believe this is right, by the British, the French and the Americans, to have early elections, which happens in some systems. In other words, to have new presidential elections, not in a year and half but within nine or ten months.

AARON MATÉ: This is after that Maidan crisis began…

STEPHEN F. COHEN: As it began [crosstalk], a negotiation with the protesters, but okay, stop occupying the building, stop trying to drive me out of office, I will agree to new elections.

AARON MATÉ: But it doesn’t matter, he’s overthrown anyway.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: Stop and think what was at stake there. Every person who wishes constitutionalism and democracy, well, in that part of the world, should seize that opportunity. Now, it is said that Putin and Obama had a conversation, and it is said that Putin said to Obama, “Do you agree to this solution? New elections?” Obama said, “I do.” Thirty-six hours later Yanukovych was driven out of office by a coup. So apart from it being it’s wrong, it’s bad, it’s stupid on the face of it, but it’s consequential, it sets precedence for American behavior. So now people are ragging on Trump about Ukraine. But we’ve forgotten what was really the turning point. I mean, it’s just been deleted.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: Stop and think what was at stake there. Every person who wishes constitutionalism and democracy, well, in that part of the world, should seize that opportunity. Now, it is said that Putin and Obama had a conversation, and it is said that Putin said to Obama, “Do you agree to this solution? New elections?” Obama said, “I do.” Thirty-six hours later Yanukovych was driven out of office by a coup. So apart from it being it’s wrong, it’s bad, it’s stupid on the face of it, but it’s consequential, it sets precedence for American behavior. So now people are ragging on Trump about Ukraine. But we’ve forgotten what was really the turning point. I mean, it’s just been deleted.

AARON MATÉ: What was the interest, what was the motive? I mean, you asked me, but I’m asking you, what was the motive of the Obama administration to do this, to have Victoria Nuland and the Ambassador to Ukraine—they were caught in a phone call basically talking about who they were going to install as the Ukrainian president—what was their…

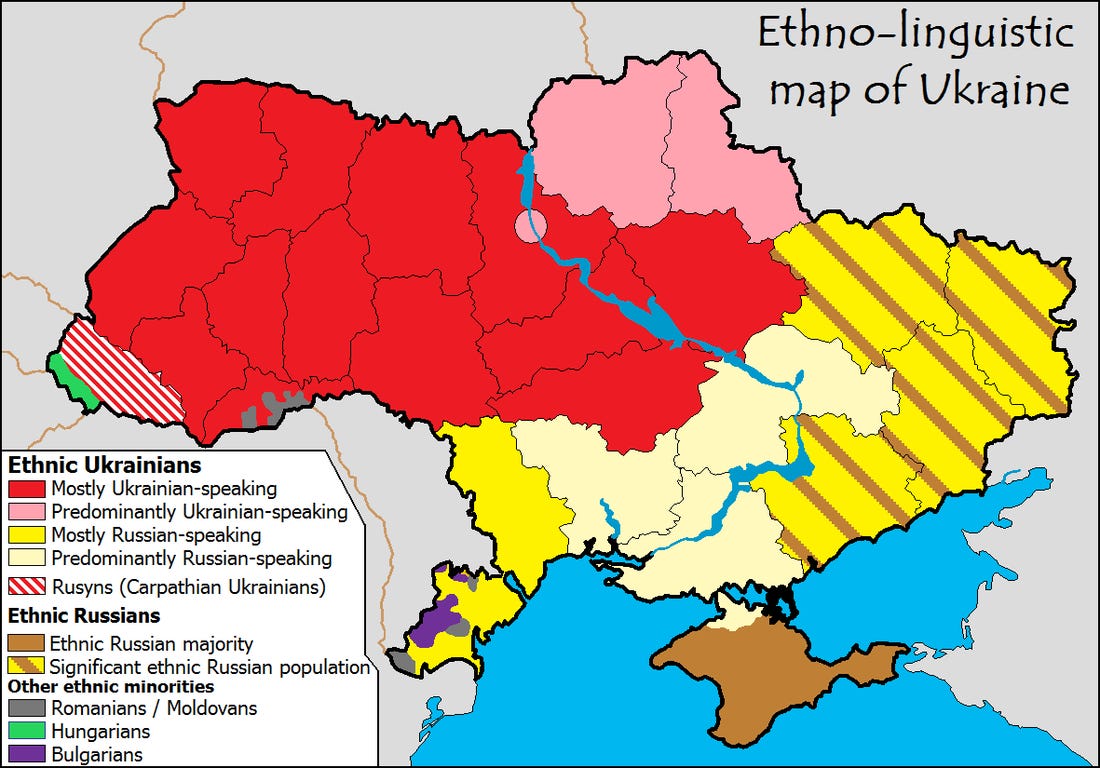

STEPHEN F. COHEN: The story gets a little torturous here, and a little legalistic. The pretext for the overthrow of Yanukovych was, is that he had been offered this wonderful trade agreement, this partnership with Europe which would make Ukraine prosperous forever but excluded Russia. And yet Russia was Ukraine’s not only largest trading partner, and still is today, by the way, which is interesting, right? But if you go into the demographics, the number of inner marriages between Russians and Ukrainians, it runs in the tens of millions. I mean, I don’t want to say they’re, they’re not one people, I mean, there is a separate Ukrainian identity. Ukraine is a diverse country. Western Ukraine looks to Poland and Lithuania, not to Russia. But, nonetheless, much of central Ukraine and almost all of southern Ukraine look to Russia as brethren, as kinfolk, as family.

Yanukovch, ousted by coup because he balked at bringing Ukraine into NATO, splitting it from Russia, its chief trading partner

To trespass in a family spat, which is not a good idea in our everyday lives, in geopolitics it’s a greater mistake. We went into something with profound cultural, familial, historical consequences that we didn’t understand. So, what was at stake at that moment was this, that the economic trade agreement that Yanukovych was offered, so-called European Partnership, I think it was, if you read it, and almost never…nobody bothered to read it. Other countries had signed it.

There was a clause that said that if you signed it, you agreed to adhere to the procedures, rules and norms of NATO. Very few people know that was included, but the Russians knew, they’ve got a lot of international lawyers. No, there…what this was, was an attempt to bring Ukraine into NATO, via the back door without saying, well, really, this is really a way of getting into NATO, it’s just benign. But it wasn’t benign. So, when Yanukovych balked, and by the way he balked also because financially it was not advantageous to him.

AARON MATÉ: He would have faced massive protests over the subsidies, the fuel subsidies that he would have had to have cut.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: With, I would then add, he, having already agreed to an early election, which meaning he would have lost the election.

AARON MATÉ: Right.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: But, nonetheless, coups are not good things in general. But in this country, with this legacy, with this notion that democracy is a really viable, viable alternative, and we, the United States represent that alternative, it was utterly discredited. Except by people…I mean, I’m not going to name the names of people who write fairytale stories about what happened, but, you know who they are, they’re very influential, they’re on television a lot, but it’s a fairytale, it’s not what happened. And, you know, to be candid, with Trump as our president, Obama looks a lot better to a lot of people than he did at the time, but the truth is, is that Obama was an exceedingly unsuccessful foreign policy president, and one of his failures of foreign policy was this, the way he handled this whole Ukrainian thing.

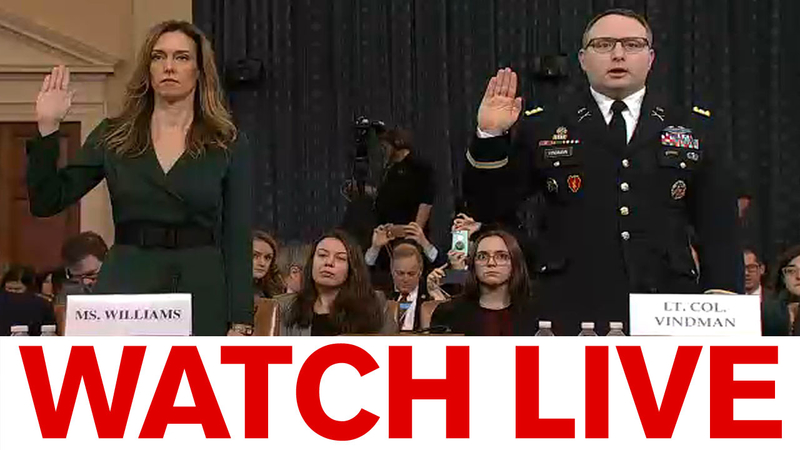

Trump impeachment inquiry

AARON MATÉ: Well, it’s interesting there, though, because here you had…you mentioned earlier that Obama did not want to send this lethal military aid to Ukraine out of concerns about it fuel… further fueling this proxy war that he helped start and about the weapons falling into the wrong hands. Trump gets into office and he actually adopts a more hawkish policy in the sense that he’s not facing all this pressure, because he’s being accused of being a Russian agent and a traitor. So, I think it’s fair to deduce that in response to that, to help get that off his back, he approves, he approves the lethal aid to Ukraine that Obama rejected. So, he, in fact, went further than Obama and actually acceded to the demands of the bipartisan foreign policy consensus in Washington, which, that leads us to this moment here, because then he puts a brief freeze on that military aid and now he’s facing impeachment.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: And he’s facing impeachment not because of the military aid but because he appeared to want something for it.

AARON MATÉ: Yeah.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: The Biden stuff.

AARON MATÉ: Yeah.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: It goes back to the question, why are we in Ukraine anyway? What were the Bidens doing there? Why were we there? The short answer is obviously, I mean, let’s do what you just pointed out. Ukraine is really far away. It represents no particular national interest or a threat to us what happens there. As you say, it’s not like our border with Canada or Mexico. For Russia, again, to make my point, it is absolutely vital. It’s simply…there’s no more existential area abutting Russia than Ukraine, whether you talk about families, shared history, military threats and all the rest.

AARON MATÉ: So, in terms of what could actually solve this, assuming that Ukrainegate doesn’t derail the prospects for peace in Ukraine, the prospects of talks between Ukraine and Russia, first of all, do you think that Russia ever gives back Crimea?

STEPHEN F. COHEN: No. No.

AARON MATÉ: That won’t happen.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: No, well, “never” is a capacious word. Not in my lifetime and not in your lifetime. The reason is, is that even though Russia acquiesced into Crimea’s kind of assignment to Ukraine, nobody in Russia actually thought it was real. And to tell you the truth, if you have look at the lack of investment or caring about Crimea, it wasn’t clear Ukraine even cared about Crimea, but the reality is, is that in…in history, in folklore, in sentiment, in culture, Crimea has always been, in the Russian mind, Russian. But it hasn’t been exclusive. I mean, they understood that Ukrainians, Tartars, Crimeans lived there, and for the most part, you know, harmoniously. So, it’s a kind of tragedy the way Ukraine got plucked out of its history.

Ukraine ethno-linquistic map/By the Business Insider

But no, no Russian leader in your lifetime, I—we should never say never, one thing I’ve learned, never say never—but it’s hard to imagine any circumstance where Russia would say Crimea goes back to Ukraine. However, a little diplomacy could go a long way, that the relationship between Ukraine and Crimea should be fulsome. By the relationship, I mean particularly, particularly involving the natural resources Ukraine has…the Crimea has a lot of resources, from fresh water [to] the minerals. There’s no reason why because it’s now legally part of Russia [that] Ukraine should be excluded. So, and I was in—I guess it’s okay to say that I was in Crimea—and I talked to the leader of the Crimean Republic, and I said, “I don’t see any reason why the best outcome isn’t a fulsome economic, cultural and political relationship between Russia, Crimea and Ukraine.” And he said, “I agree. Go convince Putin of that.” So, there’s resistance in the Kremlin, of course.

AARON MATÉ: Why?

STEPHEN F. COHEN: Well, because it’s been raised to this geopolitical stake by the outside world.

AARON MATÉ: If they give ground there then they’re giving ground to Washington.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: Yeah, but it’s gonna happen, I think. I mean, I don’t know if Putin has to leave power, if it’s that far down the road. But all the rational, whether they’re human or economic or cultural, the factors are, is that [Crimea] is kind of, belongs to both, and there’s no reason why it should be one or the other no matter whose map it’s on, if you see what I mean. And I think that’s going to happen. The, the number of tourists when I was in the Crimea two years ago, it’s hard to tell the nationalities of a lot of tourists because so many people speak Russian, but it still seems to be a very popular Russian tourist spot, obviously for Russians because Putin’s made a big effort of cheap flights and all the rest, but Ukrainians come, too, which is as it should be. There’s actually no reason to have this, this conflict over Crimea. None. Crimea has fallen victim to larger geopolitics.

AARON MATÉ: Do you think the people who drove this in Washington DC, who helped spark the Ukrainian crisis, who backed the coup, who I guess had visions of bringing Ukraine into NATO, as crazy as that sounds, do you think that they’re willing to give ground? And do you think that they can be overcome here?

Handout picture released by Cuban newspaper Granma of Cuban militiamen manning an anti-aircraft battery of Czechoslovakian-made M53 12.7 mm quad guns at Havana’s Malecon during the 1962 missile crisis. AFP PHOTO/Granma

STEPHEN F. COHEN: It would be a struggle because their perspective is, is what’s bad for Russia is good for us, so, this kind of reasoning. And we went through this from the previous Cold War, and after the Cuban Missile Crisis there was a kind of…I wouldn’t say transformation in American thinking about that Cold War, but a shift where you began to see more and more important people that say, people who could influence policy, whether in the media or politics or whatever, beginning to say maybe it’s time for us to think more about what we have in common, what we can do together. Because that was really dangerous, the Cuban Missile Crisis, you know, we almost went to war with Russia.

We need some galvanizing force like that, I guess, and I’m afraid it might come, I mean, I can imagine easily. I mean, my anxiety, which I talk about in this book, War with Russia? question mark, is a Cuban Missile Crisis-like situation between the United States and Russia. Not in Cuba, but it could be in Syria, could be in Ukraine, where we’re eyeball to eyeball militarily, right? One can imagine something going wrong or not going wrong, by intent, by provocation, because there are a lot of provocateurs out there running false flag operations. I’m not a conspiracy theorist, but false flag operations exist. So, say we get into a Cuban Missile Crisis-like situation. Kennedy had all the leeway he needed, and did Khrushchev, the Soviet leader then, to negotiate us away from war. Would Trump?

Stop and think. Here’s Trump, who’s routinely and pointlessly and idiotically referred to as a Russian puppet, right? That hasn’t gone away. I still get campaign solicitations from Democrats that say, “Send me to Congress so I can get rid of the Russian puppet.” And this lingers like a cancer in the system, it’s a malignancy. But imagine this crisis, and it’s easy to imagine in Syria, in Ukraine, wherever we’re eyeball to eyeball militarily with Russians. We now ask Trump to do what Kennedy did: to negotiate with Khrushchev’s successor Putin, away from war. Would Trump be permit… even if Trump knows how to do it, would he be permitted to do it? Because a large part of the American political class says Trump is not a legitimate president. To say that—and there’s no reason to say it, by the way, there’s no evidence that he isn’t by our rules legitimate—but to say that and keep saying it, then you have to ask yourself: and what if it came to a Cuban Missile-like Crisis? Would he be legitimate enough to negotiate the way Kennedy did, away from war? I think about that, really often.

Stop and think. Here’s Trump, who’s routinely and pointlessly and idiotically referred to as a Russian puppet, right? That hasn’t gone away. I still get campaign solicitations from Democrats that say, “Send me to Congress so I can get rid of the Russian puppet.” And this lingers like a cancer in the system, it’s a malignancy. But imagine this crisis, and it’s easy to imagine in Syria, in Ukraine, wherever we’re eyeball to eyeball militarily with Russians. We now ask Trump to do what Kennedy did: to negotiate with Khrushchev’s successor Putin, away from war. Would Trump be permit… even if Trump knows how to do it, would he be permitted to do it? Because a large part of the American political class says Trump is not a legitimate president. To say that—and there’s no reason to say it, by the way, there’s no evidence that he isn’t by our rules legitimate—but to say that and keep saying it, then you have to ask yourself: and what if it came to a Cuban Missile-like Crisis? Would he be legitimate enough to negotiate the way Kennedy did, away from war? I think about that, really often.

AARON MATÉ: Well, let me ask you then, quickly, as we wrap. Is part of this, the point then is the aim of portraying Trump as this Russian puppet, is the utility of that for these people, to actually take away his ability to make peace and make détente with Russia?

STEPHEN F. COHEN: I think there’s probably a small faction in Washington that really likes cold war and the more the better with Russia. Whether it’s for economic reasons, they sell a lot of weapons; whether because they were raised that way ideologically; whether because Russophobia is a major factor in American politics; whether because they have—I don’t want to denigrate anybody—they have a lot of Ukrainians in their constituency where they’re from; or whatever reason. But it is exceedingly dangerous and getting more dangerous by the, by the week, by the day. Trump has to be free in a crisis to negotiate as a legitimate president on behalf of the United States, and a crisis could come at any time. And if he’s not, all bets are off.

BELOW: VLADIMIR PUTIN INVOKES LOVE FOR THE PEOPLE OF RUSSIA. HOPE FOR PEACEFUL, PROSPEROUS FUTURE IN WAKE OF END OF USSR

I mean, I have to say to you, Aaron, that in four, maybe more decades of studying Russia, studying Russian-American relations, I never really took seriously the possibility of war between the United States and Russia. I never thought it was ever a…had a high probability. Today I think it’s a very high probability, partly because of this Russiagate nonsense, partly because the lack of American leadership. And I guess you could be called a Putin apologist, but I will say again as I’ve said to you on other occasions, that what Putin came to power to do was to modernize Russia, and that does not involve a cold war with the West. Period. End of story. That’s his mission. He wants to go down in history as the man who did this.

Cold war, not to mention hot war, is spoiling what he sees as his mission. He’s there for the having. And even if Trump wants to do it, it’s not clear he knows how to do it or that the people around him would advise him or even forbid him to do it, it’s not clear even with the departure of Fiona Hill and some of the other hawkish members of his administration. Because we have to remember that the one area where an American president who really has almost not autocratic but exclusive powers making foreign policy, short of doing a treaty there’s almost nothing, to use a double negative, they can’t do for better or worse. And there’s a golden moment now to be had for everybody’s security, and it’s been thwarted by this mindless…I mean, you can hate on Trump all you want, but there’s got to be a higher priority and that’s got to be international American security, and we’re letting that opportunity slip away, I fear.

AARON MATÉ: Stephen F. Cohen, professor emeritus of Russian Studies at Princeton and NYU, author of several books including his latest, War With Russia? From Putin & Ukraine to Trump & Russiagate. Professor, thank you.

STEPHEN F. COHEN: Thank you, Aaron. Always good.

Aaron Maté

Aaron Maté is a journalist and producer. He hosts Pushback with Aaron Maté on The Grayzone. He is also is contributor to The Nation magazine and former host/producer for The Real News and Democracy Now!. Aaron has also presented and produced for Vice, AJ+, and Al Jazeera.

DEMOCRACY NOW Interview with Stephen F. Cohen