December 11, 2014

“Most of bonds new credits with new interest rates, maturities, or pledges.”

Pledges: Detroit income and property taxes, state revenue sharing, assets

(VOD: photos and captions are not part of original Bond Buyer story)

CHICAGO — On Wednesday, its final day in bankruptcy, Detroit issued $1.28 billion of new debt that its bond team says required novel financing structures to satisfy both Michigan municipal law and the strict confines of Chapter 9 creditor settlements.

The four separate bond financings emerged from hours of intense negotiations with creditors, bankruptcy attorneys and restructuring consultants who didn’t always understand the nuances of municipal finance law, according to one of the lead bond attorneys in the case.

Detroit floated the four deals on Dec. 10, its final day in Chapter 9. The bulk of the proceeds paid off creditors, with some new money for the city’s restructuring plan.

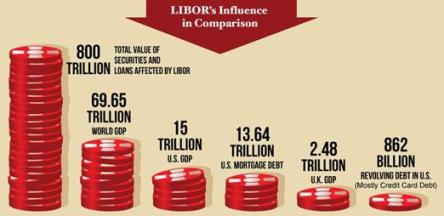

Barclay’s was a prime dealer in the LIBOR scandal, in which banks sitting on the international panel manipulated interest rates for their profit, affecting at least $800 trillion in securities and loans across the globe. In the U.S., Baltimore and other cities sued over massive losses. Detroit did not.

At least one deal, a $275 million private placement with Barclays, marks the first — and possibly last — time a Michigan city taps its income-tax revenue to secure bonds.

A $287.5 million unlimited-tax general obligation bond issue features a new structure that gives bondholders more security than they had in the past and diverts a piece of property tax millage to a new creditor group, as dictated by the city’s settlement with its ULTGO holders.

The city also issued $632 million of limited-tax GO bonds that are unsecured, with new interest rates and maturities, to pay off key creditor groups, including existing LTGO holders. A final issue, totaling $88 million and also unsecured, will go toward the insurers of the city’s certificates of participation and will be paid from parking revenues, another first for the city.

(VOD: FGIC and Syncora, the insurers of the $1.5 billion “void ab initio, illegal and unenforceable” COPS loan (as described by Detroit EM Kevyn Orr), got Joe Louis Arena, revenues from the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel and the Grand Circus Park garage, as well as uncalculated billions worth of riverfront land, in addition to the bond payments.)

Detroit filed for the largest municipal bankruptcy in the U.S. in July 2013, and bankruptcy attorneys and creditors wrangled for months over recovery rates. Once settlements were reached, it was up to the public finance professionals to figure out how the broke city would finance the payment, according to Amanda Van Dusen, chair of Miller Canfield’s public finance group and leader of the firm’s Detroit team.

Miller Canfield is Detroit’s bond counsel and also acted as its local bankruptcy counsel during the historic Chapter 9. (VOD: Miller Canfield’s Mike McGee, now the firm’s CEO, helped author Public Act 4, the emergency manager legislation later replaced with PA 436, incorporating minor changes. Unethically, he represented both Detroit and the state in negotiating a $137M loan from the state.)

Michael McGee, now CEO of Miller Canfield, in Lansing July 13, 2012 to oppose Detroit Corporation Counsel Krystal Crittendon’s lawsuit against the Consent Agreement which paved the way for Detroit’s EM takeover.

“We had dozens of participants in these negotiations who came either from the municipal finance side or the bankruptcy perspective or private turnaround sector, so we had to make it work for the restructuring plan of adjustment, but also the resulting transactions had to fit Michigan law, federal securities law, and could be traded in the municipal market,” Van Dusen said.

“There are no models for doing it. They’d come up with a resolution and then we’d figure out what the documents would look like to comply,” she said, adding that they had the additional task of maintaining the tax-exemption for the unlimited-tax GOs.

“We got there, obviously, and created a whole bunch of new structures along the way,” she said.

Many of the city’s consultants and bankruptcy attorneys — including Detroit’s emergency manager, Kevyn Orr — came from the private sector and were more familiar with bankruptcy in a private context than in a municipal one, she said.

“It was very difficult for the bankruptcy attorneys to speak one language, the restructuring professionals speak one language, and the municipal finance professionals speak another,” she said. “There’s been so few municipal bankruptcies, and certainly nothing of this magnitude, so it was very difficult to get to a point where the two types of professionals and market participants could understand each other and come to an agreement that fit both the bankruptcy model and the municipal finance model.”

Most bonds are new credits, with new interest rates, maturities or pledges

None of the four bond deals the city closed Dec. 10 were floated on the public markets.

Instead the bonds were directly placed with the creditors and participants, though they are securities that can be traded on the markets.

The deals are refundings to the extent that they replace existing bonds, but most of the bonds are new credits with new interest rates, maturities, or pledges.

“If you’ve got judgments or settlements or claims of any kind, the structures we came up with here in Detroit could be adapted to these other purposes,” Van Dusen said.

The $287.5 million unlimited-tax GO restructuring local project bonds were issued through the Michigan Finance Authority. The city had $330 million of insured ULTGOs, and the settlement called for a 74% recovery for the bondholders, with 26% of the remaining bond payments going instead to retirees.

Michigan Municipal League report shows statutory state revenue sharing lost to Michigan cities since 2003, due to legislative and gubernatorial votes.

The bonds will retain the same interest rates and maturities, but will be strengthened by two new pledges: a fourth lien on distributable state aid the city receives from the state, as well as by specific language that says the debt millage raised for the bonds constitute special revenues.

Both pledges are part of the city’s settlement with the ULTGO holders. It’s still uncertain whether the city plans to use that language with any future ULTGOs, Van Dusen said.

Of the $287 million, $279 million was delivered to the original bondholders and $7.9 million was divided among the four bond insurers to make up for payments they made in 2014 when the city had halted all debt payments.

Another $43 million of the original $330 million of GOs will remain outstanding, with the millage payments going to two income stabilization funds for the city’s retirees, as per the settlement.

“The UTGO settlement structure is particularly innovative,” Van Dusen said. “The fact that we restructured it through the MFA, and then the way it came back with additional security to the bondholders,” she said. “It helped that all of those deals, and there were 11, were insured, so we were able to work with the insurers to craft a solution.”

City awaiting ratings from bond agencies

The city has requested a rating from Standard & Poor’s, which has not yet been released. Moody’s Investors Service gave the Assured Guaranty-insured portion of the UTGO deal, amounting to $133.5 million, an underlying rating of A3 with a stable outlook. The rating is based solely on the state aid lien, Moody’s said, as well as the intercept feature that diverts the state aid directly to the bond trustee.

Wall Street ratings agencies Fitch Ratings (rep. Joe O’Keefe speaking) and Standard & Poors (Stephen Murphy to O’Keefe’s left), at Detroit City Council table Jan. 31, 2005 pushing “void ab initio, illegal and unenforceable” $1.5 B COPS loan. Then Detroit CFO Sean Werdlow (l) now COO of COPS lender SBS Financial, and Deputy Mayor Anthony Adams (r) flank them. Despite promises not to downgrade city’s debt, they did so anyway later that year. Detroit defaulted on the COPS loan several times after 2008 crash, incurring hundreds of millions in fees and penalties. Orr withdrew his lawsuit against the deal as part of the plan of adjustment.

The $275 million private placement with Barclays is the only one of the four financings to generate any new money for the city.

The bonds are secured by the city’s’ income-tax revenue, marking a first for a Michigan issuer. About half of the deal is taxable and the rest is tax-exempt.

Under the agreement, Barclays will hold the debt for up to 150 days in a variable-rate mode and the city will reissue the bonds publicly in a fixed-rate mode within that time period.

“Remarketing risk is there”–Barclays loan

Detroit Wastewater Treatment Plant workers protest second of Detroit’s disastrous information technology systems, WorkBrain. The first was DRMS. Both cost the city hundreds of millions and did NOT work. Look for more of the same back-door dealing with kickbacks to new state oversight board on any new InfoTech system.

“The remarketing risk is there,” Van Dusen said, adding that the city will seek an extension from Barclays if necessary. “But we’re already beginning to feel that the market and the credit analysts are beginning to look at the city a little differently.”

Of the $275 million, roughly $38 million of the taxable proceeds will pay off the banks that acted as counterparties on the city’s interest-rate swaps. Another chunk of the proceeds will finance a new information technology system, considered one of Detroit’s most pressing needs, as well as other capital and operating upgrades outlined in its plan of adjustment.

The taxable bonds will mature in eight years and the tax-exempt bonds in 15 years.

The city also sold $632 million of limited-tax general obligation that are unsecured and will be used to pay off various creditors. Issued as term bonds, the debt has a 30-year maturity, and will bear interest at 4% for the first 20 years and 6% for the last 10 years. Payments will be interest-only for the first 10 years.

Revenues from Detroit-Windsor Tunnel will go to Syncora along with other holdings on the Detroit riverfront.

The LTGO bonds were issued as financial recovery bonds and, like the ULTGOs, delivered directly to the creditors’ positions.

Proceeds will be used to pay off limited-tax GO holders, who settled for a 34% repayment with the city.

Another $482 million of the LTGO bond proceeds will go to the two voluntary employee beneficiary association plans that will now oversee the city’s retiree health care. Unsecured creditors with various claims pending against the city, some for as small as $1,000, could be in line for another $20.5 million of the proceeds.

Bond insurers Syncora Guarantee Inc. and Financial Guaranty Insurance Co., holders of the city’s $1.5 billion of the certificates of participation and the last and toughest last holdouts in the case, will receive $98 million of the proceeds from the LTGO deal.

FGIC will also see an additional $3.7 million of the proceeds.

Both the insurers will also be the only recipients of another borrowing’s proceeds, $88 million of LTGO bonds.

The $88 million will mark the “final financing” of the FGIC and Syncora settlements, according to Van Dusen. They will be paid over 12 years from the city’s parking revenues. Detroit sees roughly $35 million a year from parking revenues, and roughly $10 million will go the two insurers.

Lawyers and financial advisors from EM staff celebrate FGIC deal. No unions, pension systems, city workers or retirees engaged in negotiations. Note sole Black, Kevyn Orr, not named in original photo, crouching at center.

In addition to the $186 million bond proceeds — representing just over 10% of the $1.5 billion par amount — the two insurers will also get a mix of land and asset leases as part of their settlement with the city. (VOD: The last are likely worth more than the original loan.)

During the long negotiations, Van Dusen said she and others had to unlearn long-held assumptions about bond security.

“We all have a different understanding of what a security interest is than we did before,” she said. “Bond lawyers have gotten very used to thinking of GO debt one way and what is very difficult to understand is a pledge is just a promise to pay, it doesn’t create a security interest. All bond lawyers should be paying a lot more attention to what security interests will survive bankruptcy.”

Protest against Detroit bankruptcy proceedings Aug. 19, 2013, including retirees and their supporters, demanded an end to debt service to the banks. The City of Detroit reneged on its pledge and promise to retirees that they would have a livable income in their golden years. Retirees and workers recouped only 13.5 percent of their claims, while banks got 95.9 percent, re VOD story link below.

Related: