Chief planner Toni Griffin thinks so

“It is a challenging task and we take it very seriously. But I think it offers such an amazing opportunity that I can’t think of since New Orleans, I guess, which is an American city that has had the opportunity—unfortunately through a disaster—to reinvent itself, reform itself, build on its strengths and position itself in a way that it hadn’t been able to do before.”

These are the words of Toni Griffin, the urban planner/architect brought to Detroit by Mayor Dave Bing to head his “Detroit Works” or “Detroit Strategic Framework” project. The magazine Next American City interviewed her for its current quarterly edition.

(For entire article, go to http://americancity.org/magazine/article/right-size-fits-all.)

Despite the “community forums” Bing is holding regarding “Detroit Works,” Griffin, not the city’s residents, will have the most to say about the re-structuring of Detroit. She has been on board since March of this year cooking up the plan Bing claimed he does not yet have.

Griffin and her staff, along with other consultants, are being paid by the Kresge Foundation, out of a first-year grant totaling $950,000 according to Crain’s Detroit Business. Griffin and Karla Winters of Detroit’s Planning and Development Department co-chaired the five “community forums” on “Detroit Works” that took place this month, making brief appearances before turning the moderation over to staff from the Skillman Foundation and architectural firms such as Hamilton Anderson, which is also being paid by the Kresge Foundation.

What has happened in New Orleans since Katrina gives some insight into Griffin’s thinking.

Housing and population in New Orleans today

Children protesting the demolition of the New Orleans LaFitte housing development Photo by Darwin Bondgraham

“We finally cleaned up public housing in New Orleans. We couldn’t do it, but God did.”

These are the words of former 10-term Republican Senator Richard Baker of Baton Rouge, overheard speaking to lobbyists by a Wall Street Journal reporter in Sept. 2005. According to varying estimates, 1800 to 3500 people died in Louisiana during Katrina, with more still missing. More than 450,000 people were initially displaced and damage estimates were as high as $150 billion.

It has now been five years since Katrina. In its wake, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, spent over $762 million to demolish New Orleans’ numerous public housing developments, most of which were sturdy structures that had survived the flooding. Former residents, 98 percent Black, were locked out of their homes, with nowhere else to go, in anticipation of the demolition. When the city council voted to approve the plan, there were violent clashes with police.

“HUD sells the demolition as a way to improve people’s lives, but the underlying reason is much different,” Jay Arena, a former Tulane professor and a member of the Coalition against Demolition, told the After Katrina Newswire at the time.

“This is a clear violation of international human rights. This is how the United States judges other countries, based on principles that provide people with basic rights. The government is supposed to facilitate people’s return to their homes after natural disasters but this case is the direct opposite. This is a way to purge the poor form the city. It is deeply wrong and deeply racist.” (For entire article, go to: http://www.usm.edu/afterkatrina/Johnson2.html .)

A June 2008 report, “Displaced New Orleans Residents in the Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina,” sponsored by the University of Michigan and the Rand Corporation, said that 51 percent of the city’s residents had not returned within two years of the disaster, and few planned to do so.

The report concluded, “The overall implication of these results for the future population of New Orleans is likely only very modest growth from the return of still-displaced residents. The city will continue its post-Katrina experience of being older, whiter and more highly-educated, and with fewer families, children, and people out of the labor force. Our results suggest that perhaps the most effective way to increase the proportion of displaced New Orleanians who return to the city is to increase the availability of low cost housing to renters who are still away from the city but would like to return.”

Seventy percent of New Orleans children now attend charter schools

After Katrina, both the Orleans Parish School Board and the state superintendent of schools announced the district would not open for that school year, despite protests from those still living there. The Louisiana state legislature then voted to take over most of the city’s public schools.

NPR’s Amy Goodman said in 2006, “Just last week, Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings announced $24 million dollars in federal aid to Louisiana for development of private charter schools, which doubles the amount the state has already received. This federal grant was made only to charter schools–not traditional public schools. Many parents and teachers have expressed concern the move towards private charter schools is being done with little public discussion about curriculum, the efficacy of the schools, and working conditions for teachers.”

Joe Rose, Communications Director for the United Teachers of New Orleans, told Goodman, “Every teacher in New Orleans was fired. There were 7,500 school employees, everybody from cafeteria workers, truck drivers and custodians to teachers, and there were about 4,000 teachers. Solid middle class employees, career professionals who had dedicated their careers to helping try to educate the children in one of the neediest cities in the country, a city with one of the highest poverty rates, as everybody saw in the days immediately following Katrina.”

Rose said 98 percent of students in the New Orleans district were Black.

“We also have a class division within the city, where many African Americans of means, middle class African Americans, were able to send their children to or chose to send their children to Catholic schools. So New Orleans public schools were left with really the most impoverished students, and they were also in the buildings with terrible conditions, a school system that was not really adequately supported.”

Five years later, the public Orleans Parish School Board now directly administers only four schools and has granted charters to 12 others. The equivalent of Detroit’s state reform board, the Recovery School District of Louisiana, directly administers 33 schools and has granted charters to another 37.

Nearly 70 percent of children in New Orleans now attend charter schools, making it the only city in the country where more than half the student population goes to charter rather than traditional public schools. Charter school advocates there have touted substantial improvements in student testing since the transformation. But they are not taking into account the new make-up of the city’s population.

Additionally, NOLA.com said that a report from Tulane University’s Cowan Institute this year noted, “The public school population [ed.–which includes charters], like that of the city at large, has yet to return to prestorm levels: from 65,000 students pre-Katrina, enrollment is down to about 38,000 students. Those students, as a whole, are doing better in the reconstituted school system. Test scores, which once lagged far behind the state average, have risen rapidly since Katrina, though a majority of students are still failing standardized reading and math tests.

Before the storm, nearly two-thirds of the city’s schools were labeled academically unacceptable, while in 2009, only 42 percent of schools failed to meet the state standard, the report noted.”

Not surprisingly, the federal government announced in August, “Almost five years to the date after Hurricane Katrina dealt billions of dollars in damages to the infrastructure of New Orleans, the Federal Emergency Management Association [FEMA] officially announced a settlement agreement of more than $1.84 billion to cover  storm-related damages to school buildings in the city. In yet another sign of not only the renewal, but the renaissance, of New Orleans public schools, the settlement will provide for the renovation or new construction of school buildings in a community that has demonstrated consistent academic improvement since the 2005 storm.”

storm-related damages to school buildings in the city. In yet another sign of not only the renewal, but the renaissance, of New Orleans public schools, the settlement will provide for the renovation or new construction of school buildings in a community that has demonstrated consistent academic improvement since the 2005 storm.”

President Barack Obama and his Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, are both ardent advocates of charter schools.

New Orleans health system

Almost immediately after Katrina, the city closed Charity Hospital, which served the majority of the city’s poor and uninsured residents. The state-run hospital had sustained damages in the flood, but the federal government claimed not all the damages were due to Katrina, and therefore would not provide funding to re-build Charity. Patients instead were sent to Interim Louisiana State University Public Hospital, which is smaller, with half the 550 beds it had before Katrina, and offers fewer medical services.

According to an article in Fierce Health Finance, “More than 80,000 residents in eastern New Orleans still face a 30-minute drive to an emergency room, Mayor Mitch Landrieu told the Times Picayune. Last Friday, however, the city took a step toward restoring full healthcare services in the underserved area when it purchased the former Methodist Hospital from Universal Health Services for $16 million.” (http://www.fiercehealthcare.com/story/new-orleans-hospitals-still-recovering-katrina/2010-08-26. )

The feds have now decided to provide $784.8 million to REPLACE Charity, virtually the same amount the state had asked for to restore the public hospital. The money will be used instead to build a new $1.2 billion academic medical center in the Mid-City neighborhood, despite protests and likely lawsuits from preservationists. The stated purpose of the hospital is to serve not only indigent patients, but wealthier patients with insurance who would be attracted to a “state of the art” facility. The business community has a substantial number of members on the “New Orleans Academic Medical Center Initial Corporation.”

Perhaps another indication of the current priorities in the New Orleans health system was reported by The Houston Chronicle on Aug. 31 this year.

“Even five years after Hurricane Katrina, the names of hundreds of the dead remain a mystery and the death toll is mired in dispute,” said the Chronicle. “Of an estimated 1,464 victims officially recognized by the state of Louisiana, more than 500 names have not been publicly released. And Louisiana’s once-ambitious efforts to tackle dozens of related cases of missing persons and unidentified bodies ran out of money in 2006 and has never been revived.

“‘We didn’t complete the mission,’ former Acting State Medical Examiner Dr. Lewis Cataldie, a Baton Rouge-based physician who once ran the state’s efforts told the Chronicle this week. ‘I’m very angry about it.’

“. . . . John Mutter, a Columbia University professor, has been gathering personal testimonials and public records of those killed in Katrina for an effort he calls Katrinalist. Mutter estimates the true death toll will top 3,500 if those killed by the storm and by its many after-effects are accurately tallied. And yet other counts put the toll at an estimated 1,800.” (http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/nation/7177268.html)

Left Out of the Gulf’s Recovery, Black and Brown Workers Seek Unity

From Color Lines, by Brentin Mock http://colorlines.com/archives/2010/09/post_102.html

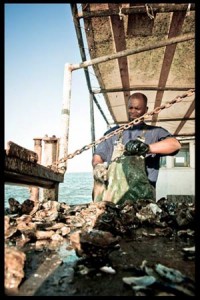

Sept. 30 — Keilen Williams had to leave his home in Pointe a la Hache, population of about 300, after Hurricane Katrina’s winds and storms devoured it. At the time, Williams, 34, was a shrimper in the small community of African-American fisher-folk who’ve worked and lived in this historically black region along the east bank of the Mississippi River for decades, and through many disasters. He’s since tried everything from setting up a shrimp business on the San Francisco piers to chasing oil clean-up work; nothing has put his family back on solid footing, and he’s frustrated.

“We used to have to do all of the work,” Williams complains, remembering the labor he invested filling the coffers of white distributors at Point a la Hache’s marina: cleaning the deck, cooking, bagging and piling the oyster sacks, hauling them off at the ports. It was poorly paid, but it was work. Now, even that is disappearing and he’s not clear where to direct his fear; he’s chosen the nearest target.

“White guys are getting Mexicans to work on their boats now because they’ll work for less money,” Williams frets. “We said we wasn’t gonna work for those slave wages.”

It’s said that once you pass a point called “White’s Ditch,” which is literally marked by a huge white fence, that you’ve entered “the black part” of Plaquemines Parish, which encompasses Pointe a la Hache and stretches to the southern tip of the peninsula. Residents call it “The End of the World,” and also “The Humble.” Black fisher-folk have lived here stretching back four, sometimes five generations.

Throughout those generations, African Americans have had to climb their way up out of slavery, poverty and disasters both natural and man-made to sustain their lives and communities. History looms over the land in the presence of Leander Perez, a racist political boss who strove to keep black people in Plaquemines segregated and powerless throughout the Jim Crow era. Perez is now deceased, but to this day some black residents will tell you that he still controls their environment.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that African Americans here began to own their own boats and leases, areas at the bottom of the sea where you could privately harvest oysters and other catch. On land, the fishers sold most of their net to big companies who bought it from them cheap and sold it at high markup to restaurants and markets across the country. They fed their families with the fish they kept and used it as currency for goods and services amongst themselves.

This is the past that informs the world black residents of Point a la Hache inhabit today. They look around that world at an ever-collapsing labor market in which they find a smaller and smaller place—and they search in vain for someone to blame.

“About 90 percent of the fishermen used to be black,” says Byron Encalade, a resident of Pointe a la Hache and president of the Louisiana Oystermen Association. “And then the Yugoslavians and Croatians, they came over and became oyster fishermen. Then the Cambodians and Vietnamese came. And recently with migrant workers from Mexico, they also have been putting in work for the oyster industry.”

Katrina came, too, knocking out everybody’s homes and boats. Given their position on this southeastern Louisiana peninsula, these communities are often among the first to get flattened, and Katrina proved completely devastating. Given that fishing is the only skill many of these residents have, when disasters delete their trade from the equation, they are left with few other options to make a living.

With the five-year anniversary of Katrina behind us and the drama of the BP oil spill officially declared over, the country’s attention has once again moved on from the Gulf. Much of last month’s anniversary coverage focused on the optimistic narrative of recovery; the region is steadily, if slowly putting itself back together. But places like Point a la Hache and families like Williams’ reveal an ugly underbelly to the new economy that’s being built. It is one in which opportunity is ever-more concentrated in a few hands, and in which profiteering capitalists and scapegoating politicians are pitting struggling workers against one another in starkly racial terms.

The Drowned Job Market

Hurricane Katrina impacted over 71,000 businesses throughout the state of Louisiana, causing the loss of over 300,000 jobs, not including the jobs of those who were self-employed, such as fishers. The New Orleans region that includes 10 neighboring parishes, among them Plaquemines, took a humongous hit, with 21 percent of its jobs lost. Employment in the oil and gas industries—which were once plentiful, as a result of the oil boom of the 1970s—was already on a downward slope before Katrina, due to the oil bust of 1986. Katrina hastened that slide, which didn’t start letting up until as recently as 2009. Although the numbers aren’t out yet, the BP oil spill has surely polluted that good news as well.

Indeed, the oil spill will very likely further tighten the shrunken labor market overall, especially in the tourism and retail industries, which both support and are supported by the fishers. It’s too early to say what exactly that impact will be in numbers, but just as after Katrina, what jobs do exist to fill the voids are in construction and clean-up. And just as with Katrina, nearly all of the contractors cashing in on the disaster capitalism with which this region has become far too familiar are white—and many have pitted black workers against brown for the cheapest labor.

Williams and his family lost everything to Katrina. As a displaced resident living in the Bay Area, where he once was stationed in the military, he found much more inclusive communities than the segregated ones he came from in Plaquemines Parish. This opened up an opportunity for him to sell Louisiana Gulf shrimp to a broader market. Like many Pointe a la Hache residents, Williams doesn’t have many skills that are transferable to industries beyond fishing. But he does have an entrepreneurial drive, and in the Bay Area, where seafood rules just as it does in coastal Louisiana, he put that ambition to use.

Williams is short, but his restless energy enlarges his presence. He has an encyclopedic knowledge of seafood, particularly shrimp—how long it needs to grow, the nuanced differences between Gulf waters and those of other coasts and continents. And while his youthful dress and vigor might lead some to cast him off as a street hustler, the scars and pocks on his face show a true fisherman’s wisdom and weathering.

Up in the north Californian bays, he was able to get Gulf shrimp sent to him in bulk. He sold them at the piers and to restaurants ready to take Tiger Prawn-sized shrimp at less than Tiger Prawn-going prices. It was his first sense that there was a demand for Gulf shrimp outside of the Gulf, and also that he could become a distributor as opposed to a fisher—and thus make more money.

When the coast began to clear back home, in early 2007, Williams moved to New Orleans instead of Pointe a la Hache, which was still having a tough time recovering. In New Orleans, he found even more success and profit than in San Francisco. He’d buy in Pointe a la Hache for $1 or $2 a pound, and then go sell in the streets for $5 a pound. In San Francisco, he says he sold for $12 to $15 a pound. But the costs of shipping bulk to north California could be imposing, if not prohibitive; in New Orleans, all he had to do was drive 75 miles south, pick up shrimp from his friends and family—or go catch it himself—and then drive it back.

Under the trademark “New Orleans Shrimp Man,” Williams sold to whoever passed by, and along the way picked up recognition from city council members, police and even state employees. Restaurants bought from him also. Nationally, he pursued diversity vendor programs so that his shrimp could be distributed to big box retailers like Sam’s Club. It was Williams’ dream to be considered the first African American distributor of Gulf shrimp in Louisiana.

His work in San Francisco and the streets of New Orleans brought him close, but the oil spill knocked the wheels off his train, and he didn’t have the resources to sustain the blow. His tiny business was nothing compared to long-entrenched players like Rodney Fox, a white distributor who controls much of the southeast Louisiana oyster trade and derivative seafood industries. Fox owns R & A Oyster Company, one of the largest oyster companies in the country, as well as Fox Trucking Company, both of which cement his stronghold on the seafood warehousing, transporting and processing industries—all major employment sources in Point a la Hache. The oyster business has been in his family’s name since 1960.

Back at the Pointe a la Hache marina—the hub from which hundreds of thousands of oysters, crabs and shrimp are collected and bought daily—Fox comes regularly to buy oysters off the fishers by the coffeesack. Oysters are bagged up at roughly 200 per sack, and Fox buys them at roughly $20 to $25 a sack—about the price some restaurants charge for just a couple dozen. He buys 800 to 1,000 sacks a day, has them processed and then ships them to restaurants and markets across the country

“Rodney gets all of this,” says Mike Bartholomew, an African American resident of Pointe a la Hache, spreading his arms across the whole marina. Fishers would like other options for their catch, says Bartholomew, but Fox is now the only one. “We’ve had strikes against Rodney,” Bartholomew explains, “but when [the fishers] are out of business, they can’t get any other employment.”

Fox sees it differently. Like Encalade, he notes the change in fishing workers’ demographics over the decades, and he assigns it to black fishers’ work ethics. “Not a lot of African Americans want to work anymore,” says Fox. “They just get free money from the government. That’s why we bring Hispanics in, because they don’t mind the work.”

New Opportunities, for a Privileged Few

Just about every major employment source for low-skilled workers in metropolitan New Orleans lost massive numbers of jobs after Katrina. In leisure and hospitality, upwards of 85,000 jobs were available in the New Orleans metro area before the storm; that number dropped by more than half in the months after. Leisure jobs were slowly returning until the recession hit, when they again disappeared. Things finally picked up again in February of this year, likely due to the stimulus act. In June, there were over 70,000 jobs available, the most there’ve been since Katrina.

The only industry that retained jobs over the past five years is construction, owing to post-disaster rebuilding, often supported by federal money. But that money has done nothing to alter the balance of power that consolidates opportunities among white capitalists and leaves workers of color fighting with one another.

Close to $19 billion in federal contracts for Katrina clean-up work has been distributed, and over $3.1 billion for Louisiana. In total, only 7.8 percent of those dollars went to small disadvantaged businesses, according to the Federal Procurement Data System, as of the last week of August. Of 26,052 vendors, only 1,166 are African-American owned-4 percent—spread out across five states. For Latino-owned businesses, the number is 985.

The same pattern has emerged in oil spill clean-up contracts. For federal contracts, only 3.5 percent of dollars are going to small disadvantaged businesses. Only five of 410 vendors—just over 1 percent—receiving contracts from the feds are black-owned, while nine are Latino-owned. In Louisiana, African Americans make up 31 percent of the population, 35.5 percent in Mississippi and 25 percent in Alabama. The percentages of Latinos are far lower in these states, though accurate population data is scarce due to the challenges of enumerating undocumented residents.

All said, many people have gained financially from disaster capitalism in southeastern Louisiana. African Americans and Latinos have not been among them.

But you wouldn’t know it by listening to the dominant political rhetoric in the Gulf. That would lead you to believe that undocumented immigrants are walking away with piles of money.

“Illegal is illegal,” crowed former mayor Ray C. Nagin while running a divisive campaign to keep his job. “So I’m not supportive of illegal aliens or illegal immigrants working in the city.” Sen. Mary Landrieu wasn’t far behind. “While the practice by subcontractors of employing illegal aliens is damaging under normal circumstances,” she warned, “at this time it is devastating.”

Folks like Williams took the cue for where to direct their job frustrations. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “I saw them working in construction, and illegal. To see Latinos start creating a working class based off construction—and they don’t buy from businesses unless they are Mexican.”

These sorts of frightened, baseless expressions haven’t died down, even five years later. Just this June, a popular talk radio station held a discussion about black-brown tensions in New Orleans. Host Gerod Brown asked Lucas Diaz, director of the advocacy organization Puentes, about the rising trend of state officials looking to pass legislation that would criminalize day laborers.

“The system favors big businesses,” Diaz explained. “Let’s think about construction. This is not a fair job access opportunity. You don’t go to an application line for these jobs. What typically happens is some sub-contractor comes up and says, ‘I’ll take you, you and you.’ Who is it that keeps that contractor accountable to any kind of equal-employment opportunity requirements? But no one is saying come in and arrest these contractors, instead they are saying to ICE to come in and get these illegals.”

Working Together for Equity

Such was the case after Katrina, when Immigration and Customs Enforcement was constantly called in to round up Latino workers—many times, conspicuously after they had completed days or weeks on a construction or clean-up project and contractors could dodge paying them. Local law enforcement and ICE officials claimed that they were in “battle” with Latino gang presence, but little evidence of this has ever emerged.

The trend recurred during the oil spill clean up. Shortly after clean up work began, St. Bernard Parish Sherrif Jack Stephens requested ICE conduct “trainings” on work visa enforcement at clean-up sites. Once ColorLines identified Stephens as the person who requested the action, he argued he’d urged ICE to act because he’s “concerned about criminal elements” using clean-up work as a cover for gang activity, as he asserted happened after Katrina. Again, there is no proof these “elements” exist.

All of this has prompted Diaz and other workers’ rights activists to build new Latino and migrant worker advocacy organizations in the Gulf. The New Orleans Worker Center for Racial Justice and its affiliates, the Congress of Day Laborers and the Alliance of Guestworkers with Dignity, have worked, along with Puentes, to ensure that not only are Latino workers’ rights protected, but also that the black-brown tensions that political leaders and corporate bosses create get addressed. STAND with Dignity emerged specifically to forge alliances between black and brown communities.

“The feelings [between African Americans and Latinos] about jobs are real,” says Llana Schler, a worker advocate for Oxfam America who co-authored a study on connecting black and brown workers. “A major obstacle has been lack of trust, which we took to mean a lack of knowledge about each other, so there have been many efforts since then to bring the two communities together.”

Denis Sariano, 24, is a Latino worker who, in the weeks after Katrina, agreed to work for a contractor who offered him $200 to $250 a day—a far higher wage than the $300 a week he was making at a restaurant in Tennessee. Sariano arrived in New Orleans during the period when the city was closed down to most of its longtime residents, and he says he saw few people among the many clean-up crews who weren’t Latinos. It was months before he saw black workers appear and when they did, contractors told Sariano that they weren’t going to be good workers because they were “lazy.”

“It made us feel superior, like we were just really great workers,” Sariano says about hearing that. Now when he hears it, he gets angry. “I know it is not true. They are not lazy, they just want fair wages. I realized that the system was using and exploiting us.”

Schler’s Oxfam report notes that less than half of the African Americans they surveyed in the area felt Latinos were limiting job opportunities. Those who did feel this way were mostly of lower income households. As for the major barrier to the communities working together, 57 percent of African Americans said it was their perception of Latinos, while 64 percent of Latinos said the same about African Americans. Both seemed to agree that a lack of social interaction was a part of that.

Meanwhile, there have been many signs of cooperative relations between black and brown communities. When Soriano and a bunch of Latino workers were arrested and jailed for standing on a corner looking for work, it was the New Orleans Survivor Council, made up of mostly African Americans, who posted their bond to have them released. And recently, when Puentes went up against state legislators looking to draft anti-Latino worker laws, these proposals were defeated in large part by the help of an African-American legislative delegation.

Dreams Deferred

Such triumphs haven’t yet materialized in Plaquemines Parish, however.

“There is a growing resentment in African American communities in Plaquemines,” says Tracie Washington, managing director of the Louisiana Justice Institute, which is working primarily with black fishers on the impact of the BP oil spill. Washington says that legislators have come down from Washington to hear the black fisher’s struggles, but “the hairs raise on the back of their necks when black fishermen voice their anger against quote ‘Mexicans’ for taking jobs in the clean-up effort.”

“Regardless if you and I feel that it is a legitimate concern or not, they feel it is a legitimate concern,” she adds. “I really think there’s got to be a way in which we can facilitate that conversation between black and Latino business advocates because at the end of the day we can’t have resentment, because it will just fester.”

Diaz of Puentes says that he welcomes those questions. He sees progress at the local level between Latino- and African-American organizations, but that there is still work to do. “I’ve been working with leaders from both communities to help them understand that it’s not about African Americans versus Latino Americans, but against big contractors.”

Meanwhile, Keilen Williams is still trying to make ends meet. He tried to move from being a start-up distributor to cleaning up oil, even going through the Vessels of Opportunity training with his wife. But he got no calls for jobs. With his shrimping and distribution dreams dashed, he’s now headed back to San Francisco, displaced once again by a different disaster. This time, though, he’s not blaming “illegals.”

“I’ve had enough of the politicians lying and saying that things are this way and that way,” says Williams. “They are making more laws against the people, and without the people’s input. It hurts me. It’s destroying me.”