Dominique Strauss-Kahn Sits in Prison While the IMF Keeps Ravaging Entire Economies Every Day

Dominique Strauss-Kahn Sits in Prison While the IMF Keeps Ravaging Entire Economies Every Day

The IMF can do far more damage trashing global economic well-being than the man behind the sex abuse scandal.

By Nomi Prins

May 18, 2011 |

The sex scandal surrounding the head of the International Monetary Fund has thrust the organization into the media’s glare. Yet, the man behind the scandal is far less relevant to trashing global economic well-being than is the institution itself.

Regardless of who takes over for the IMF’s disgraced leader, Dominique Strauss-Kahn (DSK), it’s unlikely he or she will bring about a philosophical shift in the IMF’s MO. For the IMF doesn’t care what caused devastating financial hardship to its current “focus” countries like Ireland, Greece and Portugal, nor what deal is struck in return for its aid. Saving the superpower notion of Europe and the euro as a pan-European currency by bailing out (read: lending money in return for “austerity measures” and holding fire sales of national companies) is a goal bigger than DSK.

This ideal is more important to the IMF than the financial security of ordinary citizens. Thus, the IMF will remain the validating and financing arm of the European Union (EU) and maintain the euro’s cohesiveness, no matter the cost to ordinary people. By doing so, it will continue to create debt to pay for bank screw-ups and extract repayment from innocent local populations.

This ideal is more important to the IMF than the financial security of ordinary citizens. Thus, the IMF will remain the validating and financing arm of the European Union (EU) and maintain the euro’s cohesiveness, no matter the cost to ordinary people. By doing so, it will continue to create debt to pay for bank screw-ups and extract repayment from innocent local populations.

Indeed, any concerns about the IMF altering its method of swapping loans for austerity measures just because its chief is facing felony charges, were alleviated the day he was denied bail. On Monday, Portugal, the third European country in the past year to get a bailout, was approved for a 78-billion-euro rescue package.

The price? Public spending cuts. The benefactors? The private Portuguese banks that turned around to raise cash backed by bailout-guarantees a moment later.

In Ireland, where a swish of hot money entered the country during the years leading up to the 2008 crisis, the $113 billion IMF/EU bailout did nothing to bring down the 14.7 percent unemployment rate, even as $23 billion of pension money was requested as a condition of the loan.

It’s the same story in Greece. There, the IMF has backed the EU in exacting austerity measures running the gamut from pension and wage cuts to privatization demands. To comply with its bailout agreement, Greece must continue to sell off its functioning and solvent national companies, such as its electric companies, to the highest international bidder. You know, the bidder that will care about what happens to the local cost of power. (Think Enron and California power plants a decade ago.)

But that’s what the IMF has always done. It provides loans at cheaper rates than countries would receive any other way during times of economic distress, in return for forcing them to open their economies to hot money looking for a good deal. This is based on the premise that public infrastructure and social safety nets are the cause of financial woes, and not the over-leveraged banks that funneled in the hot money to begin with.

As Andy Robinson, a journalist stationed in Athens, who writes for the Spanish paper, La Vanguardia, put it, “The IMF wants the country to sell off its grandmother’s silver to make room for more luxury beachfront hotels.”

Unfortunately for Greece, what the IMF wants more of, is exactly what caused its debt crisis — hot money that turned cold. External investment banks and funds extracted profits from the country and then headed for the hills.

Three years ago, in May 2008, Bear Stearns was handed to JPM Chase on a Fed-backed platter in Phase I of the great US bank bailout and subsidization strategy. Meanwhile, the Greek finance ministry proudly proclaimed US investment interest (i.e. hot money from banks, hedge funds or private equity funds) was strengthening.

At the time, Greek Economic and Finance minister, George Alogoskoufis further noted, “international financial organizations, such as the International Monetary Fund, also acknowledged the significant progress made by the Greek economy.” At the time, he said “an international credit crisis has not affected the Greek banking system” and “that economic conditions would return to normality in 2009.”

It didn’t work out that way. Five months later, in October, 2008, the global banking crisis arrived in Greece. The Bank of Greece had to pony up 28 billion Euros to bail out its banks (for starters). Blindly optimistic, a month later, the Greek embassy promised that the country’s economic growth would exceed the EU average for 2009-2010.

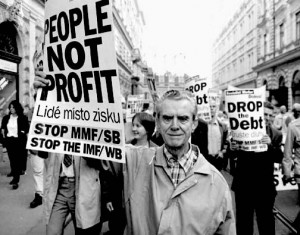

Then, things collapsed. By May, 2010, the EU and IMF pushed a $141 billion euro rescue package on Greece, with strings attached, but on the people of Greece, not the banks whose behavior trashed its economy. The result was widespread street protests.

Now, a year later, with the looming possibility of a default on its debt, and talk of more bailouts in the works, the Greek people are again taking to the streets.

The fact that public austerity measures don’t secure an economy remains lost on the IMF and EU. Instead, they want countries to sell whatever they can at rock bottom “crisis” prices, and extract the rest of the money to repay loans from citizens. The IMF and EU have just asked Italy and Spain to do more of this antiquated policy.

In retaliation, Spain’s population took to the streets in 50 cities last Sunday, protesting national austerity measures. Their chants made it clear they knew that the banks and enabling politicians caused their pain. Spanish banks are sitting on 113 billion euros of bad loans, an overhang from an international housing speculation boom gone wrong. The population faces a 21.3 percent unemployment rate, 40 percent among its youth. Austerity measures don’t create jobs.

This IMF notion of opening a country’s doors to hot money to demonstrate economic worthiness is completely misguided. The flow of fast money does not, by any measure, help the well-being of a country’s population at large. The recent uprising in Egypt, a country given gold stars by the IMF for opening its boundaries to unrestricted, irresponsible hot money to erect luxury condos and beachfront homes, is another obvious sign of this tactic’s failure.

And, yet, again and again, the IMF instills surefire economic destabilization through unaltered money-interested policies, sucking the financial life out of unarmed citizens. The IMF will soon choose a new leader to take the reigns from acting head and former JPM Chase chief economist, John Lipsky. There is talk that for the first time since its inception, this leader may come from outside the core European fold. Chances of that are remote. But, unfortunately, no matter who leads the IMF next, its legacy will continue to impart pain on the people of the countries it vows to assist. And that means more uprisings to come.

Nomi Prins is a senior fellow at the public policy center Demos and author of It Takes a Pillage: Behind the Bailouts, Bonuses, and Backroom Deals from Washington to Wall Street.