Protester Sandra Hines demands restoration of state revenue sharing to Detroit during protest at Cadillac Place State Bldg. March 4, 2013.

By Anthony Minghine

Associate Director of Michigan Municipal League

An article posted from the Michigan Municipal League’s March/April 2014 Review Magazine

An article posted from the Michigan Municipal League’s March/April 2014 Review Magazine

There have been a lot of high profile robberies over the years. The Lufthansa robbery, D.B. Cooper highjacking, the Antwerp Diamond Caper…but these crimes look amateurish compared to the state of Michigan’s Great Revenue Sharing Heist. The state has managed to pinch over $6 billion in revenue sharing from local government over the last several years. Those numbers would even get Bernie Madoff’s attention.

Michigan’s broken municipal financing model is almost a cliché. Talking about budget numbers and deficits in the billions of dollars can cause us to lose perspective. The fact is, there are a record number of local governments that find themselves in the midst of a financial crisis. Is it the result of mismanagement, neglect, or incompetence? Or is it the result of a dramatic disinvestment by the state in local government? I suggest the latter.

In my view, there are three major factors that have led communities to the financial brink: post retirement costs; a steep decline in property values; and a dramatic reduction in state revenue sharing. The third factor will be the focus of this article.

In my view, there are three major factors that have led communities to the financial brink: post retirement costs; a steep decline in property values; and a dramatic reduction in state revenue sharing. The third factor will be the focus of this article.

Post retirement costs are a huge issue that locals are grappling with. Change here is difficult at best; local governments are hamstrung with contracts and laws that make transformation slow. The property tax declines local governments have experienced could not have been anticipated to the degree they occurred, and are certainly out of the control of anyone in this state. Statutory revenue sharing, on the other hand, has been unilaterally taken by the state to solve its budget issues. It’s a fact. Revenue sharing is paid from sales tax revenues, which have been a remarkably stable source of income, and have in recent years experienced significant growth.

Breaking Down the Numbers

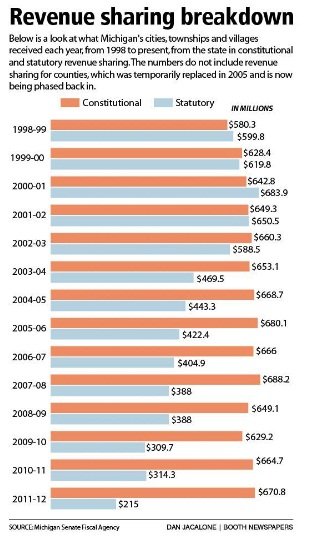

Hopefully you’ll stick with me, as I’m about to drop the “b” word. From 2003-2013, sales tax revenues went from $6.6 billion to $7.72 billion. Over that same period, statutory revenue sharing declined from over $900 million annually to around $250 million. The state is now in an enviable position—revenues that exceeded expectations. It is posting large surpluses but has failed to take steps to restore local funding.

In fact, the state is trumpeting its sound fiscal management and admonishing local governments for not being as efficient. What the state fails to mention is that it balanced its own budget on the backs of local communities. This would be like me taking your money to pay my bills, and then telling you that you need to be more responsible with your house-hold budget. In fairness, the state did experience revenue declines out of its control, much like locals experienced with property tax declines. It is different, though, in one important way—local communities couldn’t take money from others and push those tough decisions down to someone else.

In fact, the state is trumpeting its sound fiscal management and admonishing local governments for not being as efficient. What the state fails to mention is that it balanced its own budget on the backs of local communities. This would be like me taking your money to pay my bills, and then telling you that you need to be more responsible with your house-hold budget. In fairness, the state did experience revenue declines out of its control, much like locals experienced with property tax declines. It is different, though, in one important way—local communities couldn’t take money from others and push those tough decisions down to someone else.

What is most shocking is the difference those revenue sharing dollars would have made at the local level. As I stated at the onset of this article, we now have a record number of communities facing financial emergencies. It’s easy to blame local leaders, but you must consider all the facts. In most cases, communities that currently face large deficits would in contrast have general fund surpluses.

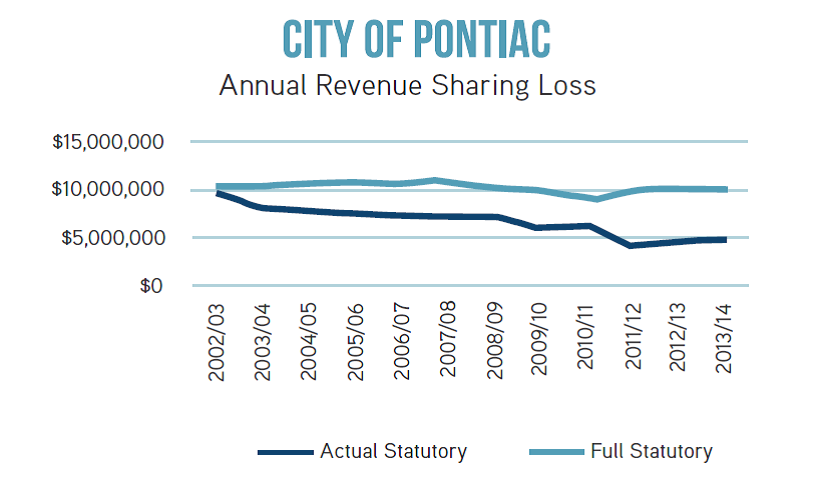

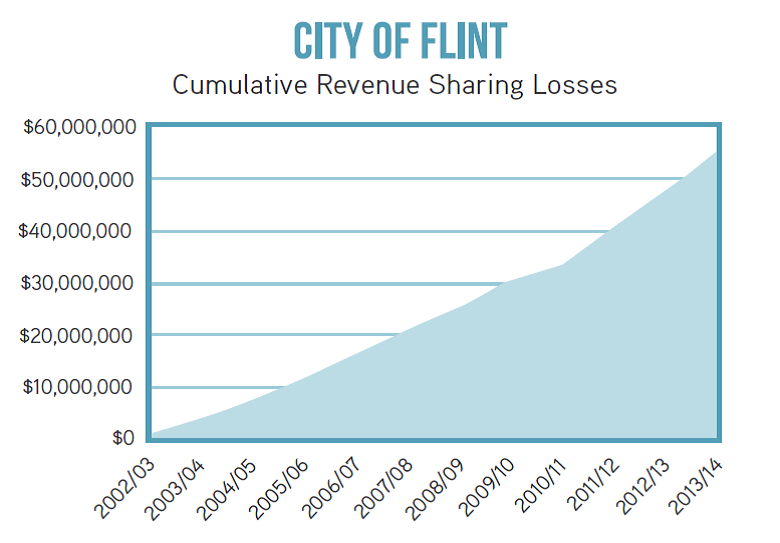

Let’s Get Specific: Four Cities’ Cuts

So what does it mean to specific com-munities? For Allen Park, an $857,000 deficit in 2012 becomes a surplus of over $5 million and would grow to a projected surplus of $7.3 million by 2014. Hamtramck’s deficit of $580,000 would have been a surplus of $8.7 million. Flint will have lost $54.9 million dollars by the end of 2014. The deficit in its 2012 financial statements is $19.2 million. Flint could eliminate the deficit and pay off all $30 million of bonded indebtedness and still have over $5 million in surplus. In Detroit, a city facing the largest municipal bankruptcy in history, the state took over $700 million to balance the state’s books.

So what does it mean to specific com-munities? For Allen Park, an $857,000 deficit in 2012 becomes a surplus of over $5 million and would grow to a projected surplus of $7.3 million by 2014. Hamtramck’s deficit of $580,000 would have been a surplus of $8.7 million. Flint will have lost $54.9 million dollars by the end of 2014. The deficit in its 2012 financial statements is $19.2 million. Flint could eliminate the deficit and pay off all $30 million of bonded indebtedness and still have over $5 million in surplus. In Detroit, a city facing the largest municipal bankruptcy in history, the state took over $700 million to balance the state’s books.

This data begs the question: did municipalities ignore their duty to manage or did someone else change the rules of the game and then throw a penalty flag at them? I see yellow flags all over the playing field. Post-retirement benefits are a huge expense and burden to local government, but we must not ignore the reality—the promises were made with a different expectation from the state as it relates to sharing sales tax revenue with local government. It’s a fact that the state has broken that promise. State leaders excused themselves from making tough choices, instead using local money to pay their bills. In the process, they have created most, if not all, of the financial emergencies at the local level.

The numbers don’t lie. Revenue sharing is the only factor that anyone has had direct control over during these difficult financial times. It is time for the state to shift gears and start investing in local government again. Hardships at the local level weren’t created by a lack of cooperation or collaboration. I would humbly submit that local governments invented the concept and the state is very late to the table. Local government officials have done, and will continue to do, their part to be prudent managers, but the goal cannot be to hang on and survive. Our goal must be to ensure that our cities are vibrant places that people will choose to live in, and that can only happen if the state fulfills its promise and responsibility to invest where the rubber meets the road, and that is at the local level.

The numbers don’t lie. Revenue sharing is the only factor that anyone has had direct control over during these difficult financial times. It is time for the state to shift gears and start investing in local government again. Hardships at the local level weren’t created by a lack of cooperation or collaboration. I would humbly submit that local governments invented the concept and the state is very late to the table. Local government officials have done, and will continue to do, their part to be prudent managers, but the goal cannot be to hang on and survive. Our goal must be to ensure that our cities are vibrant places that people will choose to live in, and that can only happen if the state fulfills its promise and responsibility to invest where the rubber meets the road, and that is at the local level.

Anthony Minghine is the associate director of the League. You may reach him at 734-669-6360 or aminghine@mml.org. Download article at mml-revenue-sharing-heist-2014.

Michigan’s cities and villages are the centers of our economy. They maintain the infrastructure and services that support the vast majority of our state’s jobs. A recent study found that Michigan’s metropolitan areas account for 89% of the state’s jobs and 88% of its gross domestic product.1 The revenue sharing distribution formula was designed to appropriately compensate the communities that support us all and the higher costs they bear. Therefore, when that formula is underfunded, Michigan’s entire economy suffers. Revenue Sharing Keeps Our Economic Engines Running.

- Water from a leaking pipe covers the gymnasium floor at the Caroline Crosman School in Detroit Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2013. How much treated water is lost this way in Detroit is anybody’s guess. Not even the city knows. But the cost is passed on in higher rates to water customers who now face a renewed threat of shut-offs on delinquent bills. The department has announced it will lay off 700 more workers, who are sorely needed to deal with the city’s aging water infrastructure. (AP Photo/Paul Sancya)

A Michigan Municipal League survey found cuts in revenue sharing have negatively impacted basic community services across Michigan. Capital projects such as street and sidewalk repairs and sewer and water improvements have been postponed; recreation and library programs have been curtailed or eliminated. Perhaps even more startling is that, according to the Michigan Commission on Law Enforcement Standards, there are nearly 2,315 fewer police officers and 1,800 fewer firefighters on the streets of Michigan since the tragedy of September 11, 2001.2

Formula Funding

Revenue sharing consists of both constitutional and statutory payments. The constitutional portion consists of 15% of gross collections from the 4% sales tax3 distributed to cities, villages, and townships based on their population. This amount is set by the state constitution. The Legislature must appropriate whatever is calculated. It cannot reduce or increase the constitutional portion.

Revenue sharing consists of both constitutional and statutory payments. The constitutional portion consists of 15% of gross collections from the 4% sales tax3 distributed to cities, villages, and townships based on their population. This amount is set by the state constitution. The Legislature must appropriate whatever is calculated. It cannot reduce or increase the constitutional portion.

The statutory portion of revenue sharing has traditionally been distributed by a formula, rather than on a per capita basis, to compensate for the significant variation in local governments’ service delivery needs, infrastructure maintenance requirements, and fiscal capacity to generate local tax revenue. Today, the program calls for 21.3% of the 4% sales tax collections to be distributed in accordance with a formula set in Public Act 532 of 1998.

Since state law sets the statutory portion, the governor and Legislature have the ability to adjust the distributed amount. They have increasingly used this ability to cover state budget shortfalls to the detriment of communities, especially during the recent recession when local budgets are already strained by drops in property value. The 1998 formula was designed to be phased in, but due to funding cuts it has never been fully implemented. If fully funded, statutory revenue sharing payments to local governments, including counties, in fiscal year 2014 would have totaled approximately $1.8 billion. Instead, the state kept $689 million, appropriating $1.1 billion to communities. This shortfall is part of a trend totaling nearly $6.2 billion in revenue sharing reductions during the last twelve fiscal years.4

Since state law sets the statutory portion, the governor and Legislature have the ability to adjust the distributed amount. They have increasingly used this ability to cover state budget shortfalls to the detriment of communities, especially during the recent recession when local budgets are already strained by drops in property value. The 1998 formula was designed to be phased in, but due to funding cuts it has never been fully implemented. If fully funded, statutory revenue sharing payments to local governments, including counties, in fiscal year 2014 would have totaled approximately $1.8 billion. Instead, the state kept $689 million, appropriating $1.1 billion to communities. This shortfall is part of a trend totaling nearly $6.2 billion in revenue sharing reductions during the last twelve fiscal years.4

In 2011, the State added requirements for local governments to obtain their statutory revenue sharing payments. Entitled the Economic Vitality Incentive Program (EVIP), locals must now comply with three categories to receive payments. The categories include accountability and transparency, consolidation of services, and unfunded accrued liability plan.

History of Shared Revenue

Michigan cities, villages, and townships receive revenue earmarked by the state constitution and statute to help pay for core governmental services such as police protection, fire service, roads, water and sewer service, and garbage collection. Known as “revenue sharing,” these funds have been tied to restrictions on local taxes. In 1939, an early instance of revenue sharing occurred when a state law removed intangible property from the local property tax base. A state intangibles tax was created and a method put in place to return funds to locals to help with lost revenues. Since that time, additional state taxes such as the sales, income and single business tax have been enacted, while the levy of local taxes has been pre-empted or eliminated. This has been done with a pledge from state officials that a portion of revenues raised from state taxes would be returned to locals—shared—for the provision of essential services.

1Source: RW Ventures, “Michigan’s Metropolitan Areas Fact Sheet”

2Source: Michigan Commission on Law Enforcement Standards and Michigan Professional Firefighters Union

3The additional 2% sales tax created in 1994 is earmarked specifically for schools.

4Source: House Fiscal Agency

Download this fact sheet at 2014-revenue-sharing-factsheet.

Protesters in Birmingham, Ala. denounce increase in sewage rates that was part of Mongtomery County’s exit from bankruptcy. JPMorgan Chase, guilty of massive bond fraud, was also forced to cut its debt payments from the County by 75 percent.