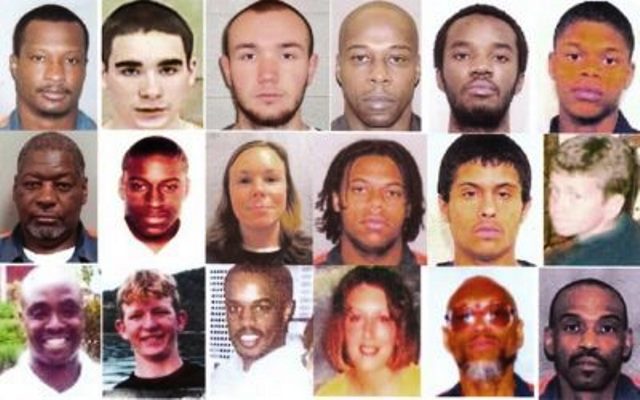

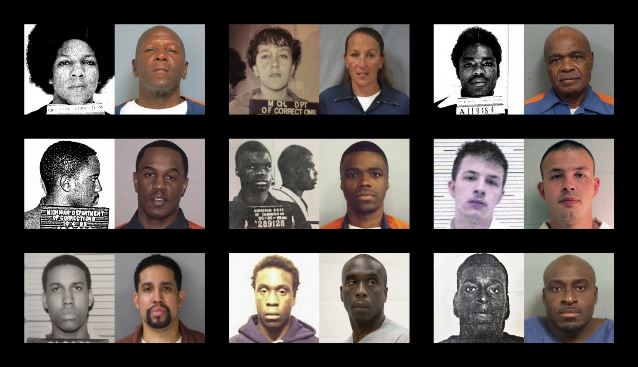

- Some of Michigan’s juvenile lifers are shown above, in VOD group photo used previously. Names below go from first row l to r and subsequent rows l t0 r. Only two of this sample have been paroled so far, seven have been re-sentenced. Some photos show juvenile lifers at current age, some at time of offense.

- Cortez Davis-El was re-sentenced to 25-60 years on April 27, despite asking for the 10-40 years his trial judge Vera Massey Jones gave him in 1994. She declared JLWOP was “cruel and unusual punishment” 18 years before Miller v. Alabama. He will not be parole-eligible for three more years.

- Raymond Carp is still serving JLWOP.

- Dakotah Eliason was originally sentenced to 35-60 years on 6-26-15, according to the MDOC website. He will not be eligible for parole for 30 years.

- Henry Hill, an original plaintiff in the ACLU’s Hill v. Snyder lawsuit against JLWOP has been resentenced to 34-60 years and should parole eligible by Aug. 2017.

- Keith Maxey, 26, is still serving JLWOP.

- Dontez Tillman, 24, was sentenced to 32.5 to 60 years on 8-5-15, and will not be parole-eligible for 24 years.

- Charles Lewis, 58, is still serving JLWOP despite hearings on the loss of his court file and Register of Actions. The hearings have been going on for over a year, with no resolution. He cites numerous legal precedents that his case should be dismissed, and that he is being illegally held in prison without a sentence.

- Jamal Tipton, 48, is still serving JLWOP.

- Nicole Dupure, 31, is still serving JLWOP.

- Giovanni Casper, 27, was re-sentenced to 40-60 years on 9/30/2016, will not be parole-eligible for 31 years.

- Jean Cintron, 25, is still serving JLWOP.

- Matthew Bentley, 34, was 14 when he went to prison. He is still serving JLWOP.

- Bosie Smith, 42, was re-sentenced to 31-60 years on March 17, 2017. He will not be parole-eligible for six years.

- Kevin Boyd, 39, is still serving JLWOP.

- Damion Todd, 48, was re-sentenced to 30-60 years on 3/20/17; he will be parole-eligible in 2018.

- Jennifer Pruitt, 41, was re-sentenced to 30-60 years on 3/2/17; she will not be eligible for parole until 2022. She was raped in prison by a guard. If her judge had resentenced her to the minimum 25-60 years, she would be parole-eligible now.

- Edward Sanders, 59, was re-sentenced to 40-60 years on 11/29/16; he was paroled July 6, 2017 after serving 41 years.

- David Walton, 60, was re-sentenced to 40-60 years on 11/29/16; he was paroled on 4/8/2017 after serving 41 years.

Below is a compilation of recent articles on the status of juvenile lifer re-sentencings in Michigan and other states. The United States Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama (2012) and Montgomery v. Louisiana (2016) that “only the rarest child” should be sentenced to die in prison.

Below is a compilation of recent articles on the status of juvenile lifer re-sentencings in Michigan and other states. The United States Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama (2012) and Montgomery v. Louisiana (2016) that “only the rarest child” should be sentenced to die in prison.

Some Michigan prosecutors push back on juvenile lifer ruling

236 out of 363 state juvenile lifers face new no-parole sentences, no action

July 31, 2017

Michigan still has one of the highest rates of juvenile lifers in the country.

Several Michigan prosecutors want to keep most or all their juvenile-lifer inmates behind bars despite Supreme Court rulings that say the punishment should be banned except for those rare offenders who are beyond rehabilitation.

Defense lawyer Deb LaBelle says that of some 363 such prisoners in the state, 236 are facing new no-parole sentences. She calls it “geographic justice.”

[VOD: LaBelle told The Nation earlier that “The system is punishing youth more harshly than anyone else.”

She cited figures showing that in Michigan between 1962 and 2004, more than 4,000 people—adults and juveniles—were charged with first-degree murder (an offense punishable by life without parole) but pleaded down to second degree, resulting in a lesser sentence.

As of June 2014, 2,221 of these people had been released, including 1,975 adults who had served an average term of just 13.1 years. As a result, LaBelle points out, adults are serving less time for the same crimes, despite being more culpable than juveniles.]

Read more about Michigan’s juvenile lifers here.

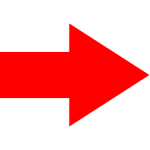

Wayne County is home to the largest number of juvenile lifers in the state. The prosecutor’s office there recommends a term of years – from 25 years to 60 years – in 82 cases while seeking new no-parole sentences in 62 others.

In other counties, prosecutors want new natural life sentences for the overwhelming majority or every inmate.

Defense lawyers say this flouts the law. Prosecutors say it’s necessary for public safety.

Benton Harbor man, 67, re-sentenced to 40-60 yrs. in JLWOP case

July 13, 2017

VOD: Berrien County Prosecutor Michael Sepic originally recommended new JLWOP for 100% of County’s juvenile lifers

Juvenile lifer Bobby Gene Griffin has spent over 50 years in prison.

ST. JOSEPH, Mich. (AP) – A man in Michigan who was sentenced to life in prison without parole as a teenager nearly 50 years ago may soon be released.

At 17, Bobby Gene Griffin was handed Michigan’s then-automatic life without parole sentence for the 1967 murder of Minnie Peaples, 84, the Herald-Palladium reported.

The law has since changed to say juveniles convicted of murder can’t receive mandatory life sentences.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that the change is retroactive – meaning that anyone already in prison who was a juvenile when committing the murder is entitled to a resentencing hearing.

Griffin and three other people broke into Peaples’ home in Benton Harbor when he was 16 years old. Court records say Griffin beat Peaples to death and sexually assaulted her while the others searched her home for valuables.

Griffin, now 67, expressed remorse in court Monday and acknowledged that he can’t reverse his actions.

“I was a teenager, but that’s no excuse,” he said. “It was sheer stupidity. I’ve grown up now. I used my time wisely. I would like to express my deep apology to Mrs. Peaples’ relatives.”

Berrien County Prosecutor Michael Sepic

Judge Scott Schofield resentenced Griffin to 40 to 60 years behind bars with credit for nearly 50 years. He’s immediately eligible for parole and is expected to be released.

“Mr. Griffin has demonstrated that not only is he capable of change, but he has changed,” said Sofia Nelson, Griffin’s defense attorney.

Prosecutor Michael Sepic said Peaples’ grandchildren have expressed disappointment in the decision.

“This was an especially heinous murder,” Sepic said. “It’s my opinion Mr. Griffin should never get out. But the law gives other factors we have to consider, and that’s what we were faced with here.”

AP Investigation: Patchwork of justice for juvenile lifers

This combination of photos shows younger and older photos of “juvenile lifers,” top row from left, William Washington, Jennifer M. Pruitt and John Sam Hall; middle row from left, Damion Lavoial Todd, Ahmad Rashad Williams and Evan Miller; bottom row from left, Giovanni Reid, Johnny Antoine Beck, and Bobby Hines. (Michigan Department of Corrections, Pennsylvania DOC, Lawrence County Alabama Sheriff’s Office, Alabama DOC (Associated Press)

By Sharon Cohen and Adam Geller | AP By Sharon Cohen and Adam Geller

July 31, 2017

DETROIT — Courtroom 801 is nearly empty when guards bring in Bobby Hines in handcuffs.

More than 27 years ago, Hines stood before a judge to answer for his role in killing a man over a friend’s drug debt. He was 15 then, just out of eighth grade. Another teen fired the shot that killed 21-year-old James Warren. But Hines had said something like, “Let him have it,” sealing his punishment: life in prison with no chance for parole.

The judgment came during an era when many states, fearing teen “superpredators,” enacted laws to punish juvenile criminals like adults, making the U.S. an international outlier.

But five years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court banned mandatory life without parole for juveniles in murder cases. Last year it made clear that applies equally to more than 2,000 who already were serving the sentence.

In this Thursday, March 16, 2017 image made from video, Henry Carpenter Warren Jr. addresses the court during a resentencing hearing for his son’s killer, Bobby Hines, seated left, at the Frank Murphy Hall of Justice in Detroit. Warren says Hines “was punished excessively. … He can go home today.” (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Prison gates, though, don’t just swing open.

The Associated Press surveyed all 50 states and found that uncertainty and opposition stirred by the court’s rulings have resulted in an uneven patchwork, with the odds of release or continued imprisonment varying widely.

Many victims’ families are battling to keep offenders in prison. “They already had their chance, their days in court, their due process,” says Candy Cheatham, whose father was killed by 14-year-old Evan Miller, the Alabama inmate at the center of the 2012 ruling. “To bring this up and make the victims’ families relive this, that’s being cruel and unusual.”

Hines, though, is in a county whose prosecutor has shown openness to paroling some juvenile lifers. Now 43, he bows his head when the murdered man’s sister, Valencia Warren Gibbs, stands to address the judge. [VOD: Wayne County has the highest actual number of juvenile lifers in the state, at 147. Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy has recommended new JLWOP sentences for 68.]

“I want him to be out,” she says. “I want him to give himself a chance that he didn’t give himself … that day.”

The Supreme Court’s decision last year was the fourth to find the harshest punishments are unconstitutionally cruel and unusual when imposed on teens. Justices cited research showing adolescents’ brains are still developing, making them susceptible to peer pressure and likelier to act recklessly without considering consequences.

Evan Miller, Miller v. Alabama

Kuntrell Jackson, Jackson v. Hobbs

Officials in states with the most juvenile life cases long argued the ban on mandatory life without parole did not apply retroactively. Now, the AP found, states are heading in decidedly different directions. Some have resentenced and released these inmates. Others are pushing back, denying any real opportunity for a reduced term or possible parole.

(Photos above are of the TWO juvenile lifers whose companion cases resulted in U.S. Supreme Court ruling outlawing mandatory juvenile life without parole. They were each 14 at the time of the crime.)

“It’s taking far too long to get … judges and prosecutors to understand that the mandates of the Supreme Court are not optional,” says John O’Hair, who saw more than 90 juveniles sentenced to life when he was prosecutor in Wayne County, Michigan, but has since criticized how some in his state are responding. [VOD: O’Hair has called for the federal government to intervene.]

Former Wayne Co. Prosecutor John O’Hair

Pennsylvania has resentenced more than 100 of its 517 juvenile lifers, and released 58. Attorneys there talk about working through all the cases in three years. Just two Pennsylvania inmates have been resentenced to life without parole, which the nation’s highest court said should be reserved for the rare offender who “exhibits such irretrievable depravity that rehabilitation is impossible.”

In Michigan, prosecutors want new no-parole terms for some 236 of 363 juvenile lifers, prompting lawsuits. And most of the cases are on hold until Michigan’s Supreme Court decides whether judges or juries should hear them.

“These are young Hannibal Lecters,” says Sheriff Michael Bouchard of Oakland County, where officials want no-parole sentences in 44 of 49 juvenile-lifer cases.

Elizabeth Calvin of Human Rights Watch says: “I don’t think anybody who is being honest about what is happening in American courtrooms can walk away and say, ‘Yes, the system has carefully culled out the worst of the worst.’”

Louisiana lawmakers spent two sessions debating what to do with 303 juvenile lifers, with district attorneys lobbying against eliminating no-parole terms. In June, the Legislature made juvenile homicide offenders eligible for release after 25 years, but prosecutors can still petition a judge for no-parole sentences.

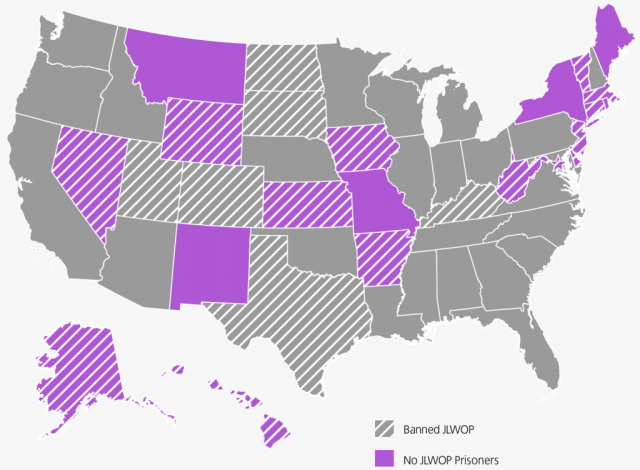

Status of JLWOP in states

Thirteen other states have passed legislation prohibiting life without parole for juveniles since 2012.

While many states have taken steps to make juvenile offenders eligible for parole, officials regularly deny release. In Missouri, the parole board turned down 20 of 23 juvenile lifers for release, says the MacArthur Justice Center, which sued. See http://stl.macarthurjusticecenter.org/news/11634

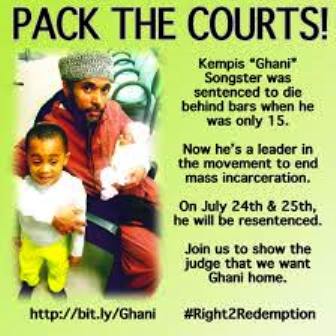

The AP found a number of juvenile lifers long ago rejected plea bargains that would have seen them released already. They include Kempis Songster, who was 15 when he joined in the Philadelphia drug house stabbing of a fellow gang member.

“You walk in there and see that they’re children and you say, ‘Wait a minute,’” says Jack McMahon, who as a prosecutor offered Songster a plea deal that could have meant freedom in as few as eight years. Songster was recently resentenced to 30 years to life, making him eligible for parole in September.

“You walk in there and see that they’re children and you say, ‘Wait a minute,’” says Jack McMahon, who as a prosecutor offered Songster a plea deal that could have meant freedom in as few as eight years. Songster was recently resentenced to 30 years to life, making him eligible for parole in September.

In many states, legal challenges are being mounted on behalf of thousands more former juvenile offenders who were sentenced to life without parole at the discretion of a judge or jury or who have parole-eligible sentences but are serving such lengthy terms they are unlikely to get out.

The Supreme Court didn’t address these cases, however, leading to different outcomes. Tennessee has refused to resentence juvenile lifers, because judges and juries there had a choice — life in prison or life with parole possible after 51 years.

In Oklahoma, juvenile life without parole isn’t mandatory, either, but offenders are getting a second look.

“On the one hand this is a mandate from the U.S. Supreme Court, and we have to comply with it,” says Scott Rowland, Oklahoma County’s first assistant district attorney. “On the other hand, you’re talking about disturbing sentences on crimes that may be three decades old, and very violent, heinous crimes. So the stakes are high.”

At Hines’ resentencing in March, the judge weighs his case before sentencing him to 27 to 60 years, making him immediately eligible for parole. He’s due to be released Sept. 12.

“I know what I’m not going to do,” he says, “and that’s get in trouble.”

Cohen reported from Detroit, and Geller from Philadelphia. Also contributing to this report were AP reporters Sheila Burke in Tennessee, Sean Murphy in Oklahoma, Juliet Linderman in Maryland, Mariah Brown in Pennsylvania and many other AP reporters across the nation.

This is the first in a three-part series about juvenile life without parole.

Most of Mississippi’s Juvenile Lifers Await Resentencing

By The Associated Press Monday, July 31, 2017 10:38 a.m. CDT

JACKSON, Miss. (AP) — In light of U.S. Supreme Court decisions, Mississippi has been starting to set new sentences for people imprisoned to life without parole for crimes committed when they were juveniles. But some say the pace has been slow, with more than half of the 87 affected offenders still waiting to be resentenced.

Andre De’Gruy, Mississippi State Public Defender

Bureaucracy and lack of deadlines have been cited as problems. Mississippi doesn’t have a uniform way to handle the issue, with 82 counties grouped into 22 circuit court districts. Andre’ de Gruy, the state public defender, said that leaves a patchwork of approaches to handling the cases on already crowded court schedules.

“It’s a serious problem in Mississippi because we don’t have an indigent defense system. We have indigent defense systems,” de Gruy said.

The U.S. Supreme Court said in 2012 that it’s unconstitutional to sentence juveniles to mandatory life without parole. Last year, the court said the ruling applied to the more than 2,000 inmates already serving such sentences nationwide and that all but the rare irredeemable juvenile offender should have a chance at parole.

87 Juvenile Lifers in Mississippi

In Mississippi, 87 offenders were affected by the rulings, including two people with life sentences imposed in two killings.

- 48 inmates are waiting to be resentenced, each in a single case

- One inmate awaits resentencing in two cases

- One inmate awaits resentencing in one case and has already been resentenced to life with the possibility of parole in another

- 27 have been resentenced to life with the possibility of parole. State law requires people to serve at least 10 years of a life sentence before being considered for parole

- Seven have received new sentences of life without parole.

- One was granted a retrial and acquitted.

- One had his conviction reversed and pleaded guilty to a lesser charge.

- One died before he could be resentenced.

Stephen McGilberry talks to his attorney at hearing.

Among the seven who have received new sentences of life without parole is Stephen McGilberry. He was originally sentenced to death in the 1994 bludgeoning deaths of four relatives in their home in the coastal town of St. Martin when he was 16. His sentence was changed to life without parole after the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty for juveniles. After a hearing in 2016, a judge again sentenced McGilberry to life without parole, and that decision is on appeal to the state Supreme Court.

The Mississippi Legislature has not set a uniform system for how resentencing should be handled.

“I don’t think you’re ever going to get the Legislature to act on this,” said attorney Tom Fortner of Hattiesburg, who has represented McGilberry and other juvenile lifers. “The people who get found guilty of committing these crimes, even when they’re juveniles … are not exactly a popular cause.”

Among the juvenile lifers waiting to be resentenced is Luke Woodham, now 36. He was convicted of three counts of murder in the stabbing death of his mother and the shooting deaths of two fellow students at Pearl High School in October 1997 — one of the earliest high-profile mass shootings on an American school campus. Woodham was 16 at the time of the attack, which wounded seven others.

Luke Woodham

Fortner filed papers in 2015 asking the Mississippi Supreme Court to set a resentencing hearing for Woodham. After local judges recused themselves, justices in November 2015 appointed a judge from another part of the state to weigh resentencing. Another attorney has been appointed to represent Woodham, and the judge has not yet acted.

“Even if the court concludes that it is not obligated to conduct a sentencing hearing … it should nonetheless conclude that Mr. Woodham has a right to be sentenced by a jury,” Fortner wrote.

One person in Mississippi was originally sentenced to life without parole as a juvenile and was subsequently retried and released. Tevin James Benjamin was 14 when he and other juveniles were arrested in 2008 and charged in the shooting death of a man at a gas station in the south Mississippi city of Moss Point. Benjamin denied taking part in the shooting, saying instead that he was at a local fair. Prosecutors said that was an alibi made up by those charged in the killing.

Tevin Benjamin

In 2010, Benjamin was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to life without parole. In 2013, the Mississippi Supreme Court threw out his conviction, saying a trial judge erred in denying Benjamin’s motion to suppress his statement to the police, which was given in violation of his Miranda rights.

In 2014, Benjamin was retried and acquitted. His first trial was in Jackson County, where the killing took place. The second trial was moved to north Mississippi’s Lafayette County.

Some attorneys will work without pay to represent people in the juvenile life without parole cases, de Gruy said. Cases can get shuffled on crowded court dockets, creating delays. Sometimes, a judge sets a new sentence. Other times, a judge lets a jury consider resentencing.“There is already, in some areas, a huge overburden,” de Gruy said. “And now you’re dumping these big serious cases back on them. It’s difficult, and we’re doing what we can to help.”

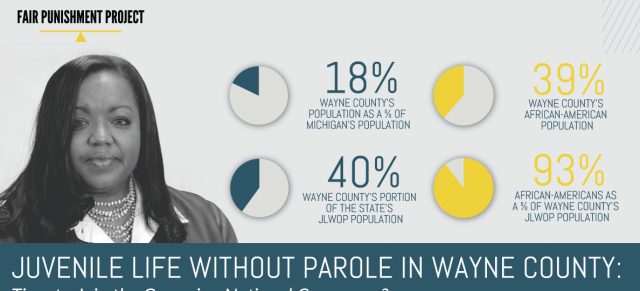

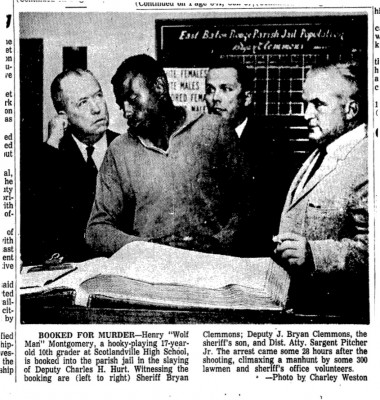

Henry Montgomery (of Montgomery v. Louisiana) re-sentenced to life WITH parole

June 21, 2017

Henry Montgomery at time of arrest

Henry Montgomery, then 69, in Angola Prison.

As reported in this lengthy local article, a defendant whose surname means a lot to a lot of juvenile offenders long ago sentenced to life without parole was resentenced today in Louisiana. Here are just some of the details of the latest chapter of a truly a remarkable case:

A Baton Rouge judge Wednesday gave a 71-year-old man convicted of killing a sheriff’s deputy when he was 17 a chance to leave prison before he dies.

Henry Montgomery has been locked up for 54 years in the killing of East Baton Rouge sheriff’s deputy Charles Hurt. But Judge Richard Anderson on Wednesday re-sentenced Montgomery to a life sentence with the possibility of parole, following a pair of recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings — including Montgomery’s own case — that say defendants convicted of murder for killings committed as juveniles cannot automatically be sent away to serve life without parole.

“This is not an easy thing for me to do … because one man is dead and the family is still living through the consequences. But the law is the law,” said Anderson, referencing the higher court decisions that said sentences of life without parole for young killers must be “rare and uncommon” and reserved only for those who display “irretrievable depravity.”

Anderson’s decision during the brief hearing came nearly two months after defense attorneys presented the judge with extensive testimony about Montgomery’s conduct in prison and the rough circumstances of his childhood. Officials from the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, where Montgomery has spent nearly all of the last half-century, described him as a trustworthy inmate and reliable worker who accumulated a remarkably low number of infractions during his time at the once-notorious prison.

Angola Prison Death Row; Montgomery originally faced execution, which was overturned on appeal.

Lindsay Jarrell Blouin, an East Baton Rouge Parish public defender who represents Montgomery, also detailed rough circumstances of Montgomery’s childhood, which she wrote included neglect, physical abuse and a lack of education. Court filings also detailed Montgomery’s mental limitations, including an IQ estimated by psychologists during his 1969 trial as somewhere in the 70s….

“He’s been a model prisoner for 54 years, he’s been a mentor and, by all appearances, he’s been rehabilitated,” Anderson said. “It does not appear (Montgomery) is someone the Supreme Court would consider ‘irreparably corrupt.'”

Montgomery was walking near Scotlandville High School on Nov. 13, 1963, when he ran from Hurt and other deputies who’d arrived to investigate a theft complaint called in by the school. Hurt tried to detain Montgomery, according to trial transcripts, and Montgomery killed him with a single shot from a .22-caliber pistol. Hurt’s partner that day wrote in an initial report that Hurt had his hands up and was backing away when Montgomery shot him.

Henry Montgomery booked at the age of 17 in East Baton Rouge, LA.

But the officer testified at trial that he was some 350 yards away and couldn’t see Hurt or Montgomery at the moment of the shooting, according to recent filings by Montgomery’s attorneys. The deputy was wearing plain clothes, Montgomery’s attorneys wrote, and the teenager told investigators following his arrest that he thought Hurt was reaching for a gun when he fired. “This was a terrible, split-second decision made by a scared 17-year-old boy who thought he was going to be killed.”

Montgomery’s 1969 conviction came after the Louisiana Supreme Court overturned an earlier verdict, ruling that widespread and often racially tinged attention to the case “permeated the atmosphere” in Baton Rouge during his first trial. The court ruled that “no one could reasonably say that the verdict and the sentence were lawfully obtained.”

Anderson also admonished Montgomery, who stood before the judge stooped with his hands closely shackled to a belly chain, to take advantage of his opportunity at freedom. Montgomery didn’t speak during the hearing and was quickly led away after the judge read out his new sentence. Blouin, his attorney, said after the hearing that Montgomery was pleased with the decision but “still grieves for the victim’s family and the impact this has had on them.”

The next step for Montgomery will be a request for a parole board hearing. He’s already served more than twice as many years as required before parole consideration and has met other requirements to apply for release. Keith Nordyke, an attorney with the Louisiana Parole Project, a nonprofit firm representing Montgomery in the parole process, said a hearing could come before the end of the year.

I believe that nicole ann dupure of Michigan ,a juvenile lifer,should get a second chance to society. She has been in prison for quite sometime and has bettered herself while being in prison. She has did alot of groups,took collage courses, and participated in everything she could. As lifers, they are not allowed to do what other inmates can do. But please, please let nicole ann dupure get a second chance in life.