Posted by 4closureFraud on March 29, 2013

Nation’s strongest bank investigated by eight fed agencies

By JESSICA SILVER-GREENBERG and BEN PROTESS DEALBOOK/NY TIMES.

As the nation’s strongest bank, JPMorgan Chase used to be known for carrying special sway with regulators. Now it increasingly finds itself in the cross hairs of federal authorities.

At least two board members are worried about the mounting problems, and some top executives fear that the bank’s relationships in Washington have frayed as JPMorgan becomes a focus of federal investigations.

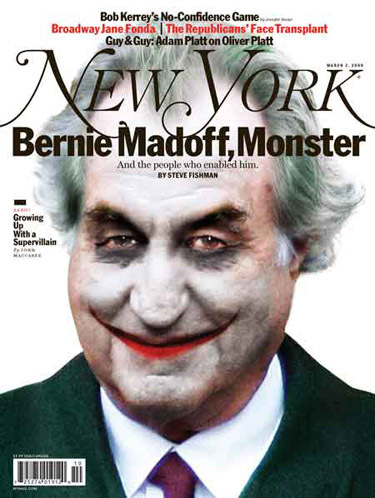

In a previously undisclosed case, prosecutors are examining whether JPMorgan failed to fully alert authorities to suspicions about Bernard L. Madoff, according to several people with direct knowledge of the matter. And nearly a year after reporting a multibillion-dollar trading loss, JPMorgan is facing a criminal inquiry over whether it lied to investors and regulators about the risky wagers, a case that could accelerate when the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other authorities interview top JPMorgan executives in coming weeks.

All told, at least eight federal agencies are investigating the bank, including the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the Securities and Exchange Commission. Federal prosecutors and the F.B.I. in New York are also examining potential wrongdoing at JPMorgan.

A recent misstep points to the growing friction between JPMorgan and regulators as well as to the concerns within the bank. JPMorgan misstated how the bank may have harmed more than 5,000 homeowners in foreclosure, according to several people briefed on the matter. The bank’s primary regulator, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, is expected to collect a cash payment from the bank to remedy the flawed review of loans, these people say.

A recent misstep points to the growing friction between JPMorgan and regulators as well as to the concerns within the bank. JPMorgan misstated how the bank may have harmed more than 5,000 homeowners in foreclosure, according to several people briefed on the matter. The bank’s primary regulator, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, is expected to collect a cash payment from the bank to remedy the flawed review of loans, these people say.

Interactive Timelines

The bank acknowledges its broad regulatory challenges. “We get it, and we are dealing aggressively with these issues,” said Joe Evangelisti, a JPMorgan spokesman.

The mortgage errors, while by themselves relatively minor, have heightened concerns within JPMorgan because they come on top of the other investigations. The increased scrutiny presents a challenge for the bank and its influential chief executive, Jamie Dimon, who was widely praised for steering JPMorgan through the 2008 financial crisis, leaving it in far better shape than its rivals. Among some executives at the bank, the worry is that the unwanted attention will undercut Mr. Dimon’s authority in Washington.

“Jamie and other executives feel terrible that the bank’s self-inflicted mistakes have put regulators in an awkward position,” Mr. Evangelisti said. He added, “We are wholly to blame for our errors and are fully cooperating with all authorities to make things right.”

Mr. Dimon has already testified before Congress and apologized for the trading losses. In response to last year’s trading blowup, the bank has also worked to root out the problems, shuffled its top executives, bolstered its risk controls and brought in a new head of compliance.

The bank’s board, which halved Mr. Dimon’s compensation in January, recently reiterated its support for him as both chairman and chief executive. JPMorgan, whose shares have soared in recent months, has recorded record profits for the last three years.

But as JPMorgan seeks to address its legal woes and restore its credibility in Washington, the bungled review of troubled mortgages could present a setback for the bank. The problems stem from January, when JPMorgan and other big banks agreed to a multibillion-dollar settlement over foreclosure abuses. As part of the pact, the bank agreed to comb through each loan file to spot potential errors, a process that the regulators will use to help determine the size of the payouts to homeowners.

While assessing 880,000 mortgages, JPMorgan overstated the potential harm for more than 5,000 loans, the people familiar with the matter said. The mistakes were not deliberate, according to a person with direct knowledge of the review, who also noted that the extent of the problem was small and that other banks were encountering their own issues with the review.

To ensure those errors didn’t cheat homeowners out of relief, JPMorgan offered additional compensation for borrowers, according to one person familiar with the matter. Still, the comptroller, which is growing impatient with JPMorgan’s mistakes, could also fine the bank, another person said.

Tensions between JPMorgan and its primary regulator were highlighted in a recent Senate report that examined the $6.2 billion trading loss. The report, by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, portrayed a somewhat defiant stance by Mr. Dimon, showing how during a brief period in August 2011 the chief executive stopped providing regulators with profit-and-loss reports about the investment bank.

Although the bank says Mr. Dimon was merely concerned about a security breach, the report says he took an adversarial tone with regulators, pushing them to explain why they needed that level of information. Mr. Dimon’s approach seemed to influence other executives, including one employee who once screamed at examiners and called them “stupid.”

Those episodes, combined with the current investigations, are costing the bank some of its influence in Washington, according to government officials who would speak only anonymously. The legal problems also pose a test for Stephen M. Cutler, the bank’s general counsel, who is advocating for the bank to take a respectful approach with regulators.

In April, according to people briefed on the matter, senior executives are expected to meet with investigators who are examining the trading loss. A handful of executives have already met with authorities, but the second round will include Mr. Dimon. While he is not suspected of any wrongdoing, the officials hope Mr. Dimon will help build a case against traders in London suspected of lowballing their losses.

The investigators will also seek information about whether some top bank executives misled investors and regulators about the severity of the losses. Even as losses mounted last year, the bank did not publicly disclose the problem for months. The bank has said that “senior management acted in good faith and never had any intent to mislead anyone.”

But the S.E.C. is also examining such disclosures. And under the Dodd-Frank regulatory law, the F.D.I.C. is investigating the trading loss, according to people briefed on the matter.

The S.E.C., F.D.I.C., Comptroller’s office and F.B.I. all declined to comment.

JPMorgan has separately come under fire for lax controls against money-laundering. In January, the comptroller hit JPMorgan with a cease-and-desist order for failures that threatened to allow tainted money to move through the bank’s vast network.

Mr. Evangelisti, JPMorgan’s spokesman, has said the bank has “been working hard to fully remediate the issues identified.”

Still, federal prosecutors in Manhattan are examining JPMorgan’s actions in the Madoff case, suspecting the bank may have violated a federal law that requires banks to alert authorities to suspicious transactions. The comptroller’s office is investigating similar issues.

“We believe that the personnel who dealt with the Madoff issue acted in good faith in seeking to comply with all anti-money-laundering and regulatory obligations,” Mr. Evangelisti said.

The federal investigation echoes claims in a 2010 lawsuit against the bank brought by Irving H. Picard, the bankruptcy trustee gathering assets for Mr. Madoff’s victims.

The suit cited internal JPMorgan e-mails sent 18 months before Mr. Madoff’s arrest, in which one employee acknowledged that a bank executive “just told me that there is a well-known cloud over the head of Madoff and that his returns are speculated to be part of a Ponzi scheme.”