Does “Lady Justice” prevail at Oakland County Circuit and higher courts?

Former Detroit police officer Burt Lancaster, with long history of mental illness and family suicide, killed girlfriend intending to kill himself

First conviction in Oakland Co. in 1994 overturned due to racial bias in jury selection

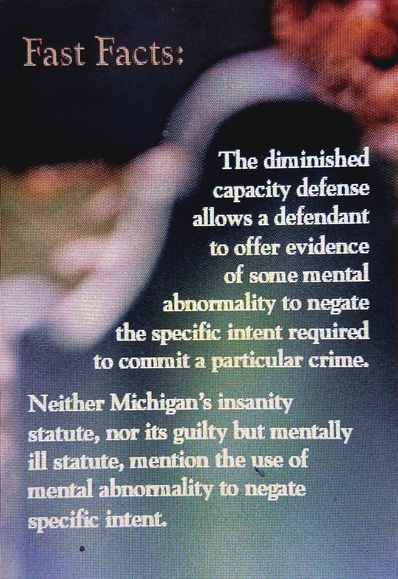

Judge denied “diminished capacity” defense in 2005 due to MSC’S controversial ‘Carpenter’ ruling in 2001; original crime occurred in 1993

Sixth Circuit Court overturned 2005 conviction, ruling that Lancaster had been denied ‘due process’ by the retroactive application of ‘Carpenter”

U.S. Supreme Court overruled 6th Circuit, found against defendant in 2012

By VOD Editor Diane Bukowski and Field Editor Ricardo Ferrell

February 11, 2020

Burt Lancaster, now age 59. MDOC photo

Detroit, MI – The first-degree murder convictions of former Detroit police officer Burt Lancaster, first in 1994 and then in 2005, for killing his girlfriend Toni King in 1993, raise broader issues.

They include racism in the Oakland County judicial system, and discrimination against the mentally ill in the Michigan state judicial system, evidenced by the 2001 elimination of a defendant’s right to raise a “diminished capacity” defense.

U.S. District Court Judge Avern Cohn dismissed Lancaster’s first conviction in 2003, based on the prosecution’s elimination of a Black juror at trial. At Lancaster’s bench re-trial in 2005, Oakland County Circuit Court Judge John McDonald refused to allow his defense of “diminished capacity.” He cited the Michigan Supreme Court’s controversial 2001 ruling eliminating the defense in People v. Carpenter (627 N.W.2d 276), despite a decades-long history of its use in the state.

McDonald contended Carpenter was retroactive. State courts and the U.S. District Court agreed, but the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court granted Lancaster a second writ of habeas corpus. They agreed that the trial court violated Lancaster’s right to due process under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution by applying Carpenter retroactively. However, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Sixth Circuit, citing the state’s right to determine its own laws.

Lancaster’s former attorney Kenneth M. Mogill won the overturn of the 1994 conviction in U.S. District Court, and represented Lancaster at his 2005 trial as well as subsequent appeals all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Attorney Kenneth M. Mogill

“To me the situation was fundamentally unfair,” Mogill told VOD. “My client went to trial the first time in 1993, but the verdict was overturned due to prosecutorial misconduct, the improper use of a juror challenge based on race. But then he was deprived of the right to raise the ‘diminished capacity’ defense at retrial. If we had been allowed to raise that, he would have had a good chance [for a reduced charge]. He would have been eligible for parole by now.”

He added, “Carpenter was a horrible ruling by the Michigan Supreme Court, based on an extremely faulty analysis of the legislative scheme. Since then, it has been hurting defendants, who are no longer allowed to have a jury consider different crimes in different categories based on different mental states.”

Prominent criminal defense attorney Kimberley Reed Thompson agreed. In a 2003 Michigan State Bar Journal article on Carpenter she said,

“The dissenting justices [in Carpenter] conclude that evidence of mental abnormality or illness should be admissible to negate specific intent and thereby afford the defendant the right to present a meaningful defense, the requirement that the state prove beyond a reasonable doubt each and every element of a charged offense, and the presumption of innocence. . . Perhaps the presentation of these significant arguments, which focus upon the basic concepts of fairness and due process in our system of jurisprudence will resurrect diminished capacity as a viable defense in the state of Michigan.”

Atty. Kimberley Reed-Thompson in shirt celebrating NFL player Colin Kaepernick’s protest. Facebook

Lancaster remains in prison today, at the age of 59. He is among many other victims of the Carpenter ruling, which left only Michigan’s insanity and guilty but mentally ill statutes in place. Neither mention the use of mental abnormality to negate the specific intent necessary for crimes like first-degree murder. Lancaster continues to deny that he intended to kill Mrs. King and says he should have been charged instead with second-degree murder.

“I am a native of Detroit and a graduate of Mumford High School,” Lancaster wrote to VOD in Dec. 2019. “I started working for the Detroit Police Department in 1985 and received a departmental citation for saving several families in a burning building on Linwood and Richton. I was disabled Dec. 13, 1986 in an on-duty scout car accident while going to a shots-fired run. I sustained injuries to both knees and a closed head injury, after which I suffered with bouts of depression.”

Trial testimony and forensic reports on Lancaster also show that he was diagnosed much earlier with major depression and bipolar disorder, attempted suicide several times, and was hospitalized for his illness at least eight times between 1987 and 1993, multiple times during his incarceration. His uncle and his younger brother both committed suicide, with Lancaster identifying his brother’s body at the medical examiner’s office while he worked for DPD.

One psychiatrist in 1987 reported that Lancaster told him the DPD had falsely charged him with conspiracy and solicitation to commit murder after he told officials that another officer was planning to kill a drug dealer. The charges were later dropped, but worsened Lancaster’s symptoms.

Lancaster said he met Toni King, then 30, in 1992. She was separated from her husband, but not yet divorced. Lancaster and King had a tempestuous 0n-again, off-again relationship for over a year, with Ms. King periodically returning to her husband and then going back to Lancaster. Lancaster claims she repeatedly hid the medication he was on, Lithium, a powerful anti-psychotic, saying, “I don’t want my husband taking crazy pills.”

In the days leading up to the killing, Lancaster told VOD, Mrs. King left for the fourth time. He said he put her belongings out on the back curb, and her brother came to the condo they shared to pick them up. Lancaster says that afterwards, her family stole his belongings from the building.

The night before the shooting, Lancaster told VOD, he went to his mother Valera Lancaster’s home and expressed his desire to kill himself due to being deeply depressed, saying he didn’t want to live anymore. He then spent the night there.

The next day, he says, he decided he was finally going to kill himself, in front of Mrs. King. He asked his mother for her .357 Magnum revolver to do so. According to her statement to police and testimony during the 1994 trial, Mrs. Lancaster refused to give her son the pistol. But he pushed open a closet door, got the gun, then left en route to his girlfriend’s job on Greenfield and Eight Mile in Southfield. Mrs. Lancaster begged her son not to leave and pleaded with him not to hurt himself. Lancaster says he left his mother a handwritten suicide note.

When Lancaster left, his mother called the police and told them that her son had taken her handgun and was going to commit suicide.

Mrs. Lancaster testified at both trials that she called 911 a second time and added that her son was going to kill his girlfriend as well, after Detroit police did not come immediately. In addition to reporting that earlier to investigators, one of her son’s subsequent doctors said she also repeated that to him. Mrs. Lancaster passed at the age of 88 in 2014.

“I told them that because I figured that if I magnified it they would come out right away and get to him before he could leave the house,” Mrs. Lancaster said. “Well, that was the era where the police were not doing too good in Detroit. And they make runs when they felt like making runs and they would be quite a long time coming to your house.”

NAG anti-busing leader Irene McCabe (center) with L. Brooks Patterson (r) in 1970.

In 1993, Oakland County’s population was 84 percent white. After 16 years as County Prosecutor, the late L. Brooks Patterson had become County Executive in 1992. He drew his support largely from his history with Irene McCabe and the National Action Group (NAG).

He represented them in the early 1970’s, fighting a court-ordered busing plan to desegregate Pontiac’s schools. The Ku Klux Klan also supported McCabe, bombing school buses and attacking ant-racists protesting a 1971 NAG rally.

Lancaster killed Toni King on April 22, 1993, in an Oakland County rife with such racism. U.S. District Judge Avern Cohn overturned his 1994 conviction for the murder in 2010, based on Mogill’s challenge to a racist jury selection process.

Lancaster’s supporters say they believe there was therefore likely a rush to judgment by police and the Oakland County Prosecutor’s Office in charging Lancaster with first-degree murder.

Mrs. King’s friend Julie Gardner testified that she and Mrs. King were on their way to lunch at a nearby Coney Island when Lancaster got to Mrs. King’s job. He offered to buy them lunch but then got into a heated dispute over financial matters with Mrs. King. Lancaster told investigators that in the course of the argument and Ms. King’s yelling at him, he panicked and shot her four times in the heat of the moment.

He said at the time of the shooting he hadn’t slept for several days or taken his prescribed psychiatric medication.

In Mental Health & Criminal Defense, Alex Bassos, JD, analyzes every aspect of a criminal case involving clients with mental health or cognitive issues and challenges attorneys to “push back against the state’s attempts to punish a person for having a mental illness.

Additionally, sources say, Burt Lancaster has agreed to submit to a polygraph exam about whether he had any intent to kill Mrs. King. The exam is pending. Lancaster, who still regrets Mrs. King’s death, and his supporters say he should have been charged with second-degree murder and would likely be eligible for parole now.

In a Dec. 13, 2016 Forensic Psychological Assessment of Parole Risk, Dr. Steven R Miller wrote, “First of all, the utter irrationality of his crimes cannot be fully understood and appreciated without taking into consideration the likely presence of some degree of ‘mental illness’ at the time of the commission of these crimes.” (Lancaster was convicted of a two-year gun felony as well as first-degree murder.)

Miller concluded his 28-page assessment of Lancaster and his progress while incarcerated and under psychiatric treatment, saying that he “presented a Low Risk to the safety or the welfare of the community.”

He included Lancaster’s statement of remorse for the crime, both for Mrs. King and her son, as well as for her mother, siblings, and nephew as well as his own family.

“I have had very deep remorse for causing the death of my beloved girlfriend Toni King [ . . .] she did not deserve for that to happen and she did not have the chance to raise her only son Lawrence King. I am remorseful because her son Lawrence King did not have the opportunity to have his mother’s love during his growing up as a child.”

Expert Lyle Denniston, a SCOTUS blog writer, was highly critical of the unanimous 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Metrich v. Lancaster, noting that they all but completely ignored the key issue in the Sixth Circuit ruling, whether the Michigan Supreme Court ruling in Carpenter was retroactive to a crime committed eight years earler. (See link below.)

“Amid signs that the ruling was a very easy one to reach, the Supreme Court on Monday allowed the state of Michigan to deny a man accused of murder a legal defense that he previously had but then lost the right to use at a second trial,” Denniston wrote. “Allowing the withdrawal of a mental defect defense after the fact, the Court ruled unanimously, did not violate the man’s constitutional rights to fair treatment. It took the Court less than four weeks to prepare that ruling.”

Related documents:

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/Lancaster-v.-Metrish-Sixth-Circuit-ruling1.pdf

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/Death-of-Michigan-diminished-capacity-defense.pdf