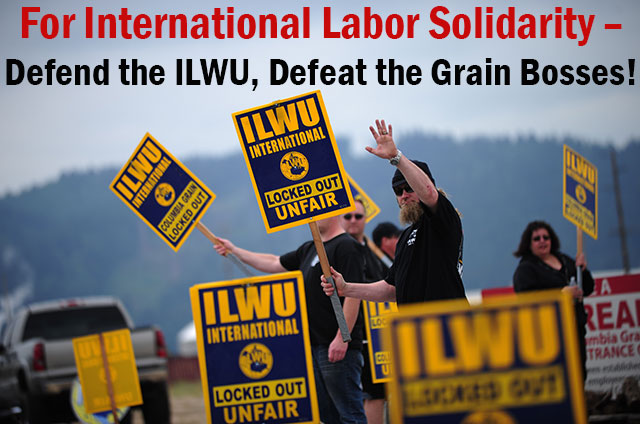

Some of the supporters of Oakman Orthopedic who ralled to save the school and stop school closings nationally on Aug. 28, 2013.

Detroiters join national call for moratorium on school closings

Demand Oakman Orthopedic remain open

Parents, students rise up as Detroit School of the Arts cutbacks announced

30.6% of school aid to banks; Detroit bankruptcy raised rates on DPS bond

By Diane Bukowski

August 31, 2013

State School Board member Marianne Yared McGuire (l) with others at rally to stop school closings Aug. 28, 2013.

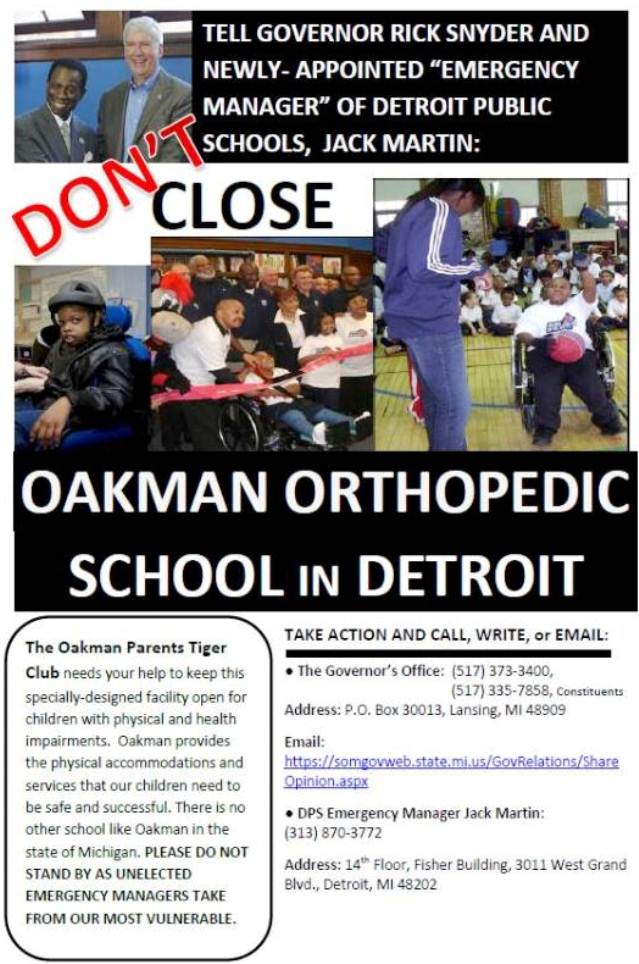

DETROIT – As outrage swells across the country about massive school closings and cutbacks, the Detroit Public School (DPS) system, the first to begin its own tidal wave of closings in 2006 with the shut-down of 50 schools, continues to wield a wide-swinging hatchet under “emergency” dictatorship.

Dozens turned out in front of DPS headquarters at the Fisher Building Aug. 28 to join other cities in a national call for a moratorium on school closings. They advocated in particular for the state-of-the-art Oakman Orthopedic School, built to accommodate the needs of uniquely disadvantaged children.

“Save our Orthopedic School, save our neighborhood schools,” protesters chanted, adding, “Hit the road, Jack and don’t you come back no more!” referring to Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder’s newly-appointed DPS Emergency Manager (EM) Jack Martin. A cacophony of car horns greeted their chants.

DSA students approach stage angrily during meeting with DPS EM Jack Martin and others Aug. 28, 2013.

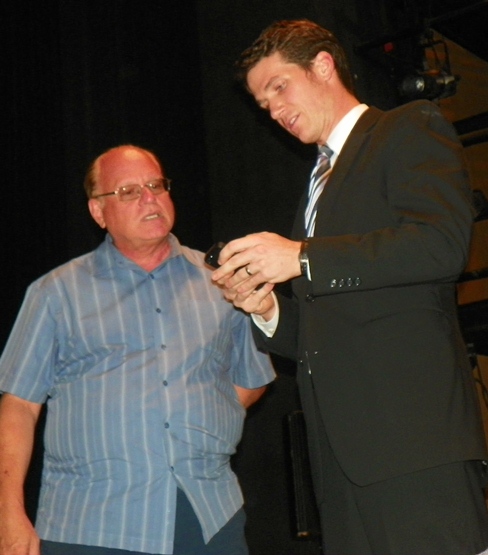

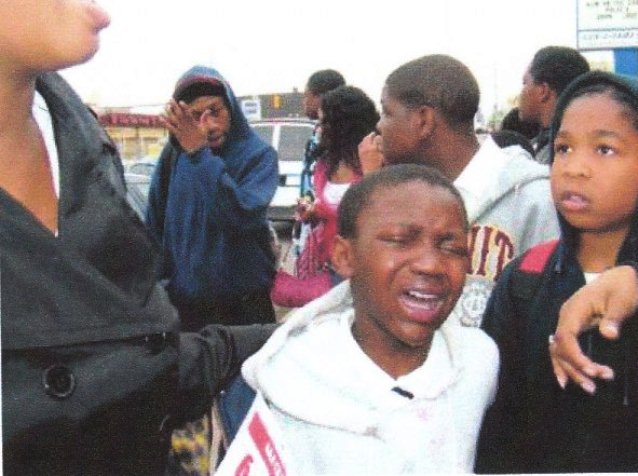

Martin has refused to meet with parents at Oakman, but that evening, parents and students at another state-of-the-art institution, the Detroit School of the Arts (DSA), forced him and DSA officers off the stage briefly. The large crowd erupted in outrage at the proposed lay-offs of skilled teachers, arts curriculum cutbacks, and the appointment of a new young white male principal in place of the Black women who previously held that job at DSA.

Parent Qiana Lynum told Fox 2 News, which was barred from entering the meeting, “This is a crown jewel—the only school of its kind in the country. I moved here from Atlanta just so my daughter could attend DSA.”

DPS plans to close 28 more schools, pay 30.6% of state aid to the banks

The DPS Deficit Elimination Plan for 2013-14, signed by former DPS EM Roy Roberts, says the district plans to close 28 more schools from 2014 to 2016. DPS has been decimated by closures for nearly a decade now, with state per-pupil aid siphoned off to charter schools, 13 schools in the state-created Education Achievement Authority, and the district’s debt to the banks.

Aliya Moore, president of Oakman Tiger Parents Club. Keep the Vote No Takeover leader Helen Moore is in background.

During the 2013-14 school year, DPS set aside $107,261,000 for that debt, taken out of $350,285,000 in state per-pupil aid, according to a letter DPS sent Aug. 15 to the Bank of New York, which oversees the payments. See DPS Set aside requirements 8 15 13.

Aliya Moore, President of the Oakman Tiger Parents Association, told VOD that Martin has refused to keep Oakman open despite recommendations by both the Detroit and Michigan Boards of Education. Forty percent of Oakman’s 300 children have severe disabilities which the school was built to accommodate, with accessible entrances, a single floor layout, rooms for diaper changes and catheterizations, and a wheelchair accessible greenhouse and playground.

“There is no other school like Oakman in Michigan,” Moore said. “But they are forcing our children to go to Nolan and Henderson schools this fall. We attended very phony open houses for both these schools, where most of the buildings were taped off, making us stay in small areas. They have some of Oakman’s staff at Noble assigned to a gym. A special ed therapist said none of her equipment has been moved to Noble and that there is no sink in the nursing station there.”

Oakman Orthopedic School.

Moore said cosmetic changes to the grounds at the schools such as shrubbery and flowers have been added, but that parents fear the Oakman building is being “tampered with.”

“First they told us there were $900,000 worth of repairs needed at Oakman, now it’s $3 million,” Moore said. “We haven’t been able to go inside there since Aug. 13, and then they only allowed us in one hallway and stood outside the bathroom when we used it to make sure we didn’t try to go anyplace else.”

“No child should have to go to a school like that.”

Photos of conditions at Noble are displayed during protest.

Marianne Yared McGuire of the State Board of Education attended the protest, standing next to a woman with a poster plastered with photos showing deplorable conditions at Nolan.

“No child should have to go to a school like that,” McGuire said, “let alone those going to Oakman. “Eleanor White, the head of Special Education for the Michigan Department of Education (MDE), said everything would be ready by the start of the school year at Nolan and Henderson.”

Sixty Oakman parents and children traveled to Lansing to meet with the MDE last month, according to another protester, but personnel there told them no one was available when they arrived. She said the MDE never called them back or sent an email.

“They’re supposed to serve us because special ed is totally supported with state and federal tax dollars,” she declared angrily.

Helen Moore rallies protesters.

Lamar Lemmons is president of the Detroit Board of Education, which the state has stripped of most of its powers.

“This is taxation without representation,” he told the crowd. “It’s enough to start a revolution. The board has voted continuously against the closure of Oakman and other schools. Oakman was working, and now we’re being punished for our success. They closed the Detroit Day School for the Deaf and a school for pregnant and parenting teens before this. They go after the most vulnerable. We demand that the state reimburse DPS for all the money it owes us. There are hundreds of millions in funds that the state has refused to take because it would mean they would have to get rid of the Emergency Managers.”

More protesters kept coming. Cynthia Lowe and Marguerite Maddox (with helper dog)are at left.

Board member Elena Herrada added, “They go after the low-hanging fruit in order to gentrify so rich whites can move in. They closed Southwestern High School, and now it’s Oakman and the Detroit School of the Arts. It’s very strategic. The parents are overwhelmed because they have no alternatives.”

For more information from Journey for Justice, which sponsored the national day of protest against school closings, go to Journey for Justice fact sheet. Also see http://voiceofdetroit.net/2013/08/26/detroit-joins-natl-coalition-to-call-for-moratorium-on-school-closings-rally-wed-aug-28-3-pm-dps-hq-fisher-bldg/.

DSA FACES LOSS OF ARTS TEACHERS, CUTS TO ARTS CURRICULUM

(SEE LETTER BELOW STORY FROM DSA FOUNDER DR. DENISE DAVIS-COTTON.)

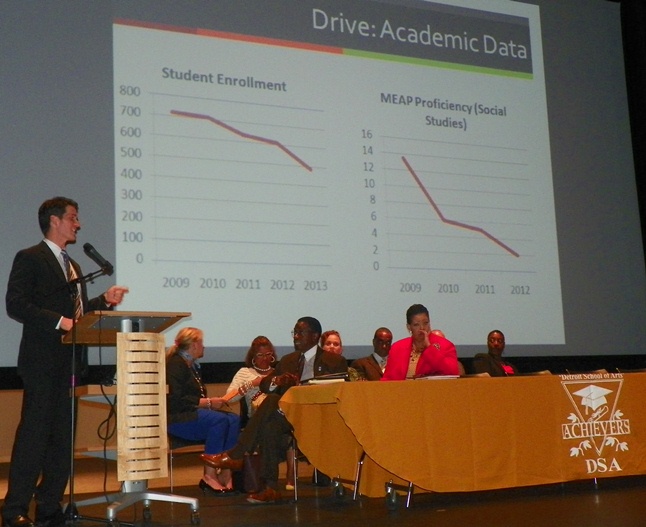

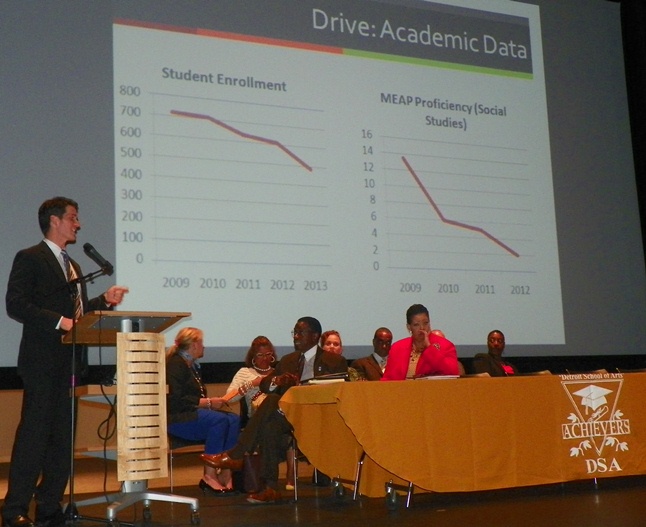

At DSA, parents and students at a packed meeting erupted in anger when officials announced that the only discussion of proposed cuts would come from questions submitted on cards. The officials said only six questions from the cards would be addressed. The school’s new principal, Robert Harvey, showed slides and claimed that DSA is running a $5 million deficit due to decreased student enrollment. Lay-offs and cutbacks in the arts curriculum were abruptly announced the week before schools opened.

DPS Superintendent Karen Ridgeway speaks as DPS EM Jack Martin (next left) listens approvingly.

As EM Jack Martin sat by, smiling in approval, Superintendent of Academics Karen Ridgeway claimed that DSA had previously been allowed to have 30 teachers although its student enrollment of 500 qualified it for only 21. She said the school must return to its previous enrollment of 750 to 800 students to regain staff, and announced that applications were being handed out.

Eight teachers were slated for lay-offs, with the band and music tech programs among others cut.

A student called out, “We don’t have enough teachers already. The classes are overcrowded. How can we have a School of the Arts without arts teachers?”

Audience members at DSA meeting begin rising in protest.

In Dec. 2012, DSA staff reported in a letter, “It is the 12th week of school, yet there are still 45 classes that are oversized to the capacity of anywhere between 39 students to 54 students. We have been told we can’t hire more teachers because it is not in the budget, the one that we still do not have.”

The minutes of the DSA Governing Council for April 15, 2013, state that the “Governing council was told that budget for next year would not change. They were also promised no ‘sweeping layoffs.’” Go to DSA 2013 4-15 Minutes_Approved_FINAL for full minutes.

Martin and other DPS officials rush off stage as crowd gets angrier.

The staff letter says that, “Doug Ross’ office, the Office of Innovation and Charter Schools, receives 3 percent of our operating budget,” and says the school can never get assistance for its needs from that office. It says Ross has been siphoning funds meant for DSA to charter schools. Ross is a long-time advocate and founder of charter schools in Detroit. (Go to DSA Staff Statement Opposing Self Governance to read full letter.)

Helen Moore challenges Martin and DPS officials during DSA meeting Aug. 28, 2013.

Also, City of Detroit Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr declared bankruptcy in July. The Wall Street Journal later reported in August, “Detroit’s public-school system is expected to pay a hefty yield premium as it looks to sell $92 million in debt Tuesday, about a month after the city sent shock waves through the municipal-bond market with its record bankruptcy filing.”

The article estimated investors in the $92 million bond would earn 4.5 percent instead of the normal 0.18 percent, meaning millions more siphoned off to the banks from the DPS budget.

After return to stage, DSA Principal bends down to hear students’ protests.

DSA is one of nine “self-governing small high schools,” with 2,800 students, according to the district’s 2013-14 Deficit Elimination Plan. Go to DEP DPS 2013 14.

“Decisions related to curriculum, staffing, budgeting and operations will be determined at the school level enabling the individual Governing Councils to maintain autonomy in their educational programs,” says the plan. “This will allow them to make decisions that best meet the individual needs of their students, shifting authority under this education model.”

Members of the Governing Councils are appointed. During the meeting, parents and advocates said the governing council is virtually non-functional and demanded that it be disbanded and the school be returned to regular DPS status. They asked that all lay-offs and curriculum changes be canceled immediately.

Natasha Baker read off questions from the cards, each of which elicited loud applause from the audience.

- DSA Principal Robert Harvey (r) refused to talk to VOD at end of meeting.

“Why was a new principal chosen and no one else interviewed,” asked one individual. Ridgeway claimed there were interviews, but an audience member declared that a lie.

“What is going to happen to our talented staff?” asked another individual. Ridgeway replied that they are being transferred to other schools.

Anger from parents and students in the meeting continued to rise.

Helen Moore, co-founder of Keep the Vote No Takeover, stood and declared, “This is our school, our meeting. You are not answering the parents’ questions. You are not allowing the parents to be in charge.”

Shortly afterwards, Martin, who had been silent, and other officials left the stage briefly while a parent of their choice, Cheryl Valentine, took over. She asked the audience to work with the EM and take applications for more students. She asked parents to sign up with the Detroit Parent Network, an organization set up by private organizations including the Skillman Foundation.

Parent Christal Bonner addresses audience as former speaker, Karen Valentine, listens from stage. Bonner is pointing to principal and others cowering in a corner of the stage.

Parent Christal Bonner then took the mike.

“I am a parent of six children, one just graduated from DSA in June, and another is supposed to be coming here in September for the band program,” Bonner said. “I am very concerned because I want DSA to be a full-functioning fine arts school. The kids here support each other, and there has been an artistic, friendly family environment. This school used to be called the School of the Fine and Performing Arts. We shouldn’t be forced to go out and sell chicken dinners to support arts in our schools.”

DSA students and parents flock around Christal Bonner to sign petitions demanding no lay-offs, no curriculum changes, return to DPS regular status.

Parents and students flocked around her to sign petitions based on demands she presented, including restoration of all teachers and a full arts program, and return to regular DPS status instead of the “self-governing” model. She and Moore called on the audience to attend rallies at DPS headquarters Aug. 29 and 30 to present the petitions to Martin.

Bonner said the DSA format was based on that of the Booker T. Washington School of the Fine and Performing Arts in Dallas, Texas, the only other school of its kind in the country, except for Interlochen in Michigan.

“They don’t want too many of US there, and it’s a private school,” Bonner declared.

DPS EM Jack Martin, guarded by police and staff, kneels to talk to parent.

Sharetta Strong, parent of a DSA graduate, told VOD, “I’m very concerned. We’ve been working with them all year, and have been told nothing about a $5 million budget gap.”

Charlene Ward, parent of a DSA 11th grader, said, “The self-governing board has been all but dissolved. This is the first time most of the parents have seen those numbers over the course of the school year. This was supposed to be a partnership. What kind of partners let you go belly under? They feel they can do the same thing over and over. We can only take so much. We have an EM over the city, and an EM over the schools. They do not really understand what we need. We need arts at a performing arts school. My son was so excited to be in the vocal jazz program. We know what the school needs. To yank it just as the school year begins is not right.”

DPS under EM Jack Martin later issued the following statement to Fox 2 News (it is not posted on the DPS website):

Parent Christal Bonner (r) and Helen Moore (center) gather petition signatures and talk to audience members

“The decision to make changes to the number of instructional positions at Detroit School of Arts is being reviewed by Detroit Public Schools Academic Leadership and Emergency Manager. It is anticipated that, going forward, staff changes of this nature will also be reviewed with representatives of the school’s Governing Council. Detroit Public Schools remains committed to supporting not only the Detroit School of Arts, but also adding arts/music enrichment back to all of our elementary and middle schools for the 2013-14 school year.

DSA Principal shows charts showing alleged enrollment and achievement drops.

However, we must also remain vigilant in operating our school system in a fiscally responsible manner so that the District can be sustainable for future generations of Detroit students. In recent years, DSA has consistently operated at a deficit that the District can no longer afford to cover, therefore consideration is being given to eliminating some instructional positions and having DSA’s newly restructured leadership team perform both their administrative work and take on some instructional responsibility based on proven models. All of these administrators are licensed and qualified in the respective areas of instruction which they may take on. Further, the District’s ongoing enrollment drive shows hopeful signs of future growth for the school, with approximately 50 new students having enrolled this summer. The district is also actively seeking supplemental funding to assist in instructional areas where budgetary constraints might cause programs to be affected.”

STATEMENT FROM DSA FOUNDER DR. DENISE DAVIS-COTTON

Arts help stimulate the soul. When the arts are diminished in schools, one shreds part of the souls of children. -Dr. Denise Davis-Cotton, Founder and First Principal, Detroit School of Arts

Dr. Denise Davis-Cotton, DSA founder and first Principal

Detroit School of Arts (DSA) was designed to provide enriched academic arts opportunities for students under the tutelage of high quality academic arts instructors. DSA was founded on the principles of leadership integrity and community engagement. These two qualities helped advance DSA into national and international acclaim.

It is difficult and painful to learn about the disruption of DSA’s educational attainment, which began by removing the school from under the auspices of the Detroit Public Schools and forcing her to exist in an unwarranted aggressively inadequate autocratic governance structure. Regretfully, providing a high quality education to DSA’s students was replaced with a regressive ideology of immobilizing educational advancement.

DSA Orchestra

It is disconcerting to learn about the educational bureaucratic practices and processes that silenced the community’s voices by denying them democratic participation in selecting the school’s leadership. DSA’s positive school climate and culture suddenly became a cesspool for incompetent competents imposing a villainous will on students, parents, teachers, and staff.

DSA student violinist.

The most pejorative act to DSA’s academic integrity is the recent displacement of stellar teachers with impeccable professional records. There is no sound or appropriate rationale to justify these displacements. Detroit Public Schools is in a position to correct a wrong that resulted in harming DSA, which is held hostage under a depreciatory governance structure, unqualified school leadership, and an amputation of first-rate arts instructors; specifically, N. Burrell, M. Malabad, and C. Malabed.

The demise of the DSA’s educational programs and removal of exceptional instructors is unjustifiable and reprehensible. The current autocratic school governance structure appears to produce despondently inept and deceptive leadership decisions that fail to advance DSA’s mission and vision.

Award-winning DSA singers and teachers Dec. 17, 2008

To reconcile these issues, it is of paramount importance and urgency to begin to restore DSA’s credibility by re-instating DSA to the Detroit Public Schools and re-instating the displaced teachers. DPS can support DSA by acting immediately to remove the school from an existing ineffective, unqualified, disorganized, despotic governance and school leadership structure that has diminished and harmed DSA’s school community and paralyzed thriving programs. Furthermore, DPS can immediately re-call the displaced teachers.

DSA jazz musicians

The ramifications and repercussions of ignoring the requests of DSA’s school community could continue to impair the learning experience for students and impede DSA’s growth. Support is needed (at this time) to save not only the institution but the future of the citizens of Detroit. One only need to be reminded that there are four things that help construct a society: laws, education, religion, and the arts. Failure to save DSA, an institution that has proven to instill arts within the Detroit community, will be judged historically as another step in the genocide of Detroit’s culture.

For more information on the fight against school closings and cutbacks, (for Oakman), contact Helen Moore (313)-934-7721 and helen-moore@att.net; Aliya Moore (313)-758-8552 and oakmantigerrparentorganization@yahoo.com

Maulana Tolbert (313)-341-5929 and detroit.nlc@gmail.com.

For more information on DSA situation, contact Christal Bonner @ (313)350-2393 or bonnerchar@yahoo.com . She is also asking that concerned parents, students and supporters start calling and emailing the following:

Jack Martin, EM- (313)870-3772 ; jack.martin@detroitk12.org

Karen Ridgeway, Supt (313)873-4493; karen.ridgeway@detroitk12.org

Natasha Baker, Innovator (313)873-3485 ; natasha.baker@detroitk12.org

Willie McAllister, Music Supr (313)873-7706; willie.mcallister@detroitk12.org

Robert Harvey, Principal DSA; (313)494-6000; rharve1@yahoo.com