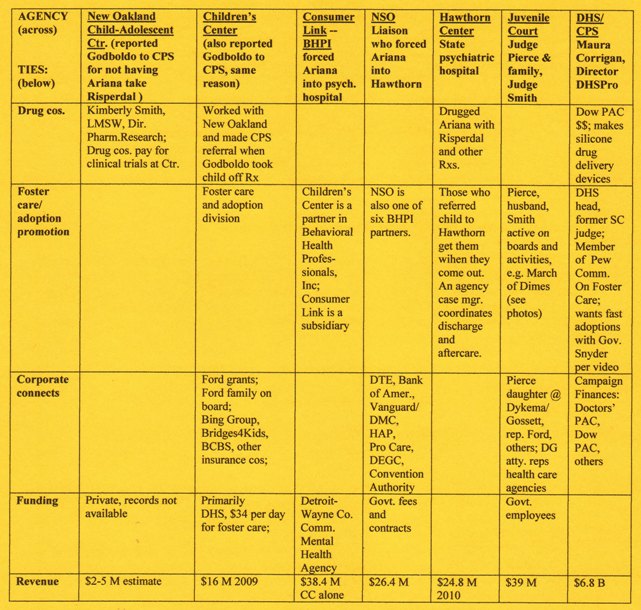

CENTER THAT REPORTED GODBOLDO TO CPS HAS $$$ TIES WITH DRUG COS.

Other organizations, individuals in case connected in possible conflicts of interest

By Diane Bukowski

August 7, 2011

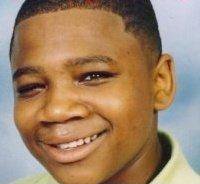

The New Oakland Child-Adolescent & Family Center, which reported Maryanne Godboldo to Child Protective Services for taking her 13-year-old daughter off the controversial drug Risperdal, has had paid connections with pharmaceutical companies since at least 2004.

According to the Center’s website, Kimberly Smith, LMSW, of China, Michigan, has been Director of Pharmaceutical Research for all its facilities since 2004. It says she also provides “clinical support and supervision” for the Clinton Township facility. Additionally she heads the Center’s Office of Recipient Rights.

“Presently, Kimberly is coordinating Adult and Pediatric CNS [Central Nervous System] Clinical Trials for a number of pharmaceutical companies and has been for the last ten years,” says the site.

The center, a private facility, is headquartered in Livonia and has sites in Centerline, Clarkston, Clinton Township, Davisburg, and West Bloomfield.

VOD contacted Ms. Smith at her office Aug. 4. She admitted that she is paid by the drug companies she works with, and that trials she is paid to conduct are among those carried out at New Oakland’s facilities. She refused to give further information on specific drug trials, saying that information is “private.”

“We must sign a confidentiality agreement with the company,” she said. She claimed reports are only published after the FDA approves a drug.

That statement is only partially true, according to the U.S. National Institutes of Health, on their site at http://ClinicalTrials.gov.

The site indicates, “The Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA or US Public Law 110-85) was passed on September 27, 2007. The law requires mandatory registration and results reporting for certain clinical trials of drugs, biologics, and devices.” (For further information click on http://prsinfo.clinicaltrials.gov/fdaaa.html.)

A clinical trial of Depakote, sponsored by Abbott Laboratories, for which New Oakland recruited participants, was listed on the site while it was still ongoing with the following details:

“Clinical Trial: An Outpatient Study of the Effectiveness and Safety of Depakote ER in the Treatment of Mania/Bipolar Disorder in Children and Adolescents. . . .New Oakland Child/Adoles. and Family Center, Clinton Township, Michigan, United States; Recruiting: Kimberly Smith MSW, 586-412-5321 ext. 310, ksmith@newoakland.org, Ismail Sendi, M.D. Principal Investigator.”

Ms. Smith said that parents are required to complete a detailed form when their child participates in such a study, but said she did not have a blank copy of the form she could send to VOD. A sample consent form for a drug research study can be viewed by clicking on http://www.niams.nih.gov/Funding/Clinical_Research/invest_form.asp

Drug companies’ payment of medical professionals both to recommend, market and prescribe their products is a national scandal, according to many sources. (Click on VOD post http://voiceofdetroit.net/2011/08/07/u-s-johnson-johnson-wrongly-marketed-risperdal-to-kids/. )

But even beyond the New Oakland Center’s drug connections, those involved in seizing Ariana Godboldo-Hakim are connected to each other in a tangled web, getting big bucks for children they take from families, and for medical treatment, including drugs, that are given to the children.

Government officials including Judge Lynne Pierce, Department of Human Services chief Maura Corrigan, and others also have their ties. (See chart for condensed info.) As Supreme Court Justice, Corrigan was a member of the Pew Commission on Children in Foster Care and also of the ultra-right wing Federalist Society. (Click on Pew Commission on Children in Foster Care to read its executive summary.) She is now head of the Michigan Department of Human Services, and recently partnered with Governor Rick(tator) Synder to advocate speedy adoptions of foster care children. Many believe this may lead to speedier termination of parental rights as well.

Maryanne Godboldo first took her daughter to The Children’s Center, located at 79 W. Alexandrine in Detroit, when she began experiencing adverse reactions to the immunizations she received in September, 2009. Unknown to her at the time, the Children’s Center is one of six partners in Behavioral Health Professionals, Inc (BHPI), a non-profit based in Michigan.

The others are Development Centers, Inc., Hegira Programs, Inc., Neighborhood Services Organization (NSO), New Center Community Mental Health Services, Northeast Guidance Center, Southwest Counseling and Development Services, and The Guidance Center.

BHPI is the parent organization for ConsumerLink and CareLink, which network with insurance companies and refer children to the various partners and other organizations.

Amber Kozlowski, a “social worker/hospital liaison,” testified Aug. 5 that she was responsible for Ariana’s admission to Hawthorn Center on March 25. There, her prosthesis was removed in violation of her disability rights, she was re-medicated with Risperdal and other drugs, and allegedly became the victim of sexual abuse, as stated in a police report filed by her family.

Kozlowski said she works for NSO directly and contracts with ConsumerLink for the hospital liaison part of her job. NSO’s board of directors includes executives from various health and insurance agencies, including the Detroit Medical Center, Pro Care Health Plan, and the Health Alliance Plan.

Kozlowski said she works for NSO directly and contracts with ConsumerLink for the hospital liaison part of her job. NSO’s board of directors includes executives from various health and insurance agencies, including the Detroit Medical Center, Pro Care Health Plan, and the Health Alliance Plan.

But that’s not all about Children’s Center, which is primarily funded by the Department of Human Services. It has its own foster care/adoption division, and is funded at the rate of $34 per day for foster care provision, according to state budget documents. Such funds, which are also funneled to numerous other private foster care agencies in the state, originate with the federal government.

The Children’s Center also receives substantial grants from Ford Motor Company, and three Ford family members sit on its board. Judge Lynne Pierce’s daughter Lauren Phillips is an attorney with Dykema Gossett, and the Judge has frequented the firm’s offices for various events, including a Women Lawyers of Michigan luncheon this past March.

Dykema-Gossett counts Ford among its top clients. Dykema Gossett also has a separate Family Law practice, run by Attorney Joanne Lax, which assists clients with adoptions.

When such matters become thorny, according to their website, “In the sensitive area of family law, many of the services our clients require fall outside the realm of legal counsel. In these cases, we can recommend a network of highly experienced counseling agencies and professionals to provide the appropriate assistance and advice.”

Lax also specializes in Health Care Law at the firm. According to its website, “Joanne represents health systems, hospitals, prepaid in-patient health plans, nursing homes, homes for the aged, assisted living facilities, hospices and home health agencies” regarding various matters.

These include state and federal regulatory compliance, and litigation and hearings in numerous areas such as licensure and certification, Medicare/Medicaid and provider enrollment, human subject research and clinical trials, medical records access and retention, and patient rights and biomedical ethics, including those involving recipient rights and minors and legally incapacitated individuals.

Pierce’s husband Raymond Andary is also an attorney, although his practice is dissimilar to their daughter’s. However, he recently participated in a 2011 March of Dimes Caribbean Getaway July 20, which raised money to support children with serious illnesses. The March of Dimes this year gave a grant to the Northeast Guidance Center, one of BHPI’s six partners.

In the video below, Gov. Snyder and DHS Director Maura Corrigan swear in new DHS workers, most for CPS, as they pledge to speed up adoption process, imperiling rights of biological parents.