(Earlier broadcast above by Channel Four, Oct. 11, 2016)

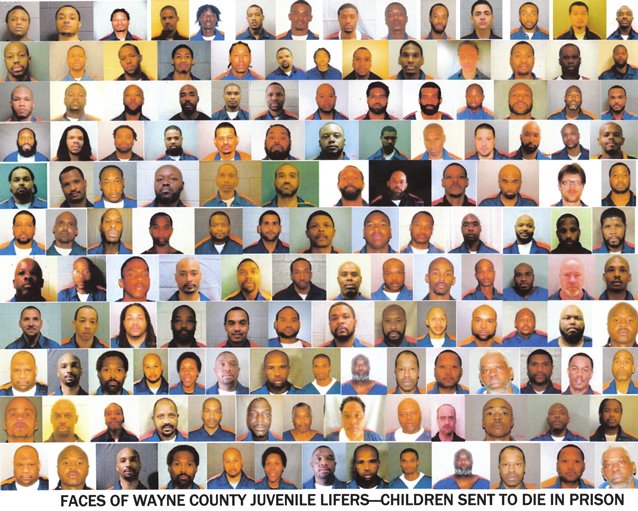

#TAKETHEKNEE! Justice for Lewis, 247 juvenile lifers; Fri. Oct. 6, 8 am @ Frank Murphy, St. Antoine/Gratiot, hearing @ 9 am, Judge Qiana Lillard Room 502

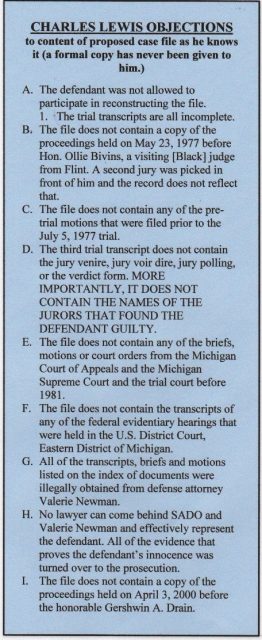

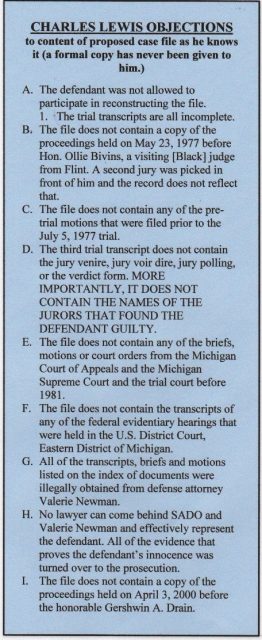

Lewis, attorneys to argue issues in his objection to Judge Qiana Lillard’s Nov. 18 ruling to re-construct his official court record

Lewis says legal precedent bars re-construction of criminal case file, demands immediate release

Battle continues after nearly 2 yrs. of post-conviction hearings triggered by U.S. Supreme Court rulings against juvenile life w/out parole

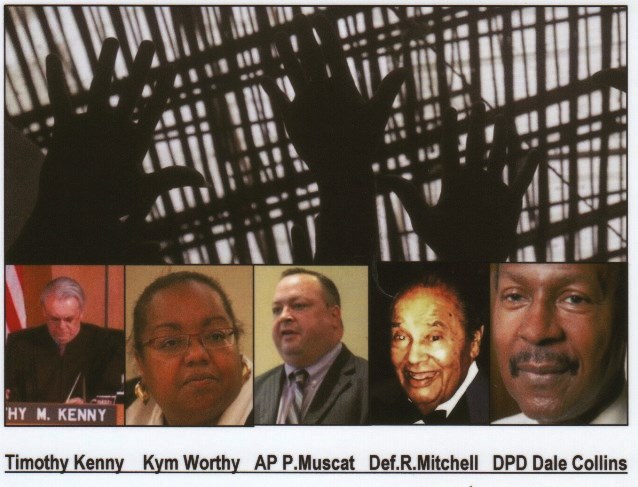

Pros. Worthy, AP Dawson, argue for renewed JLWOP sentence

By Diane Bukowski

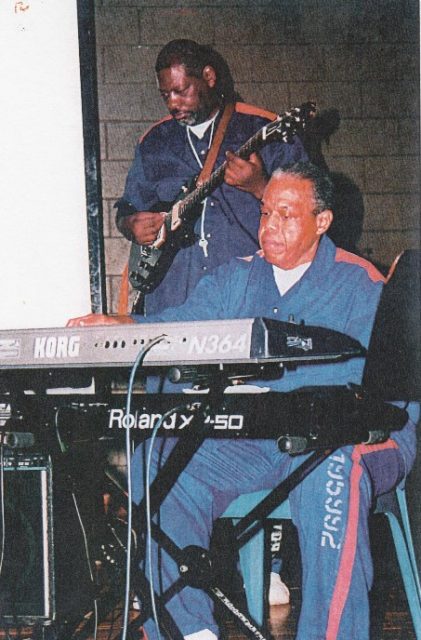

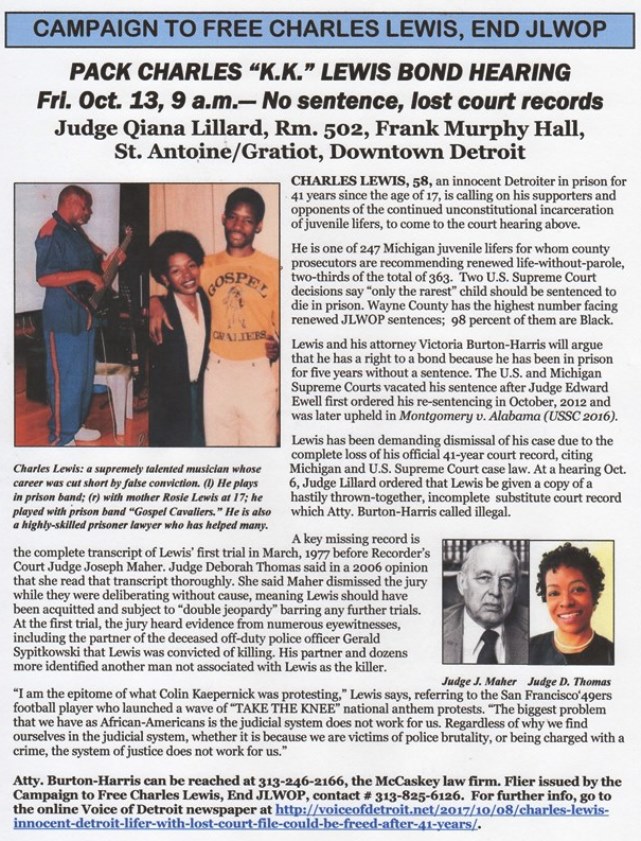

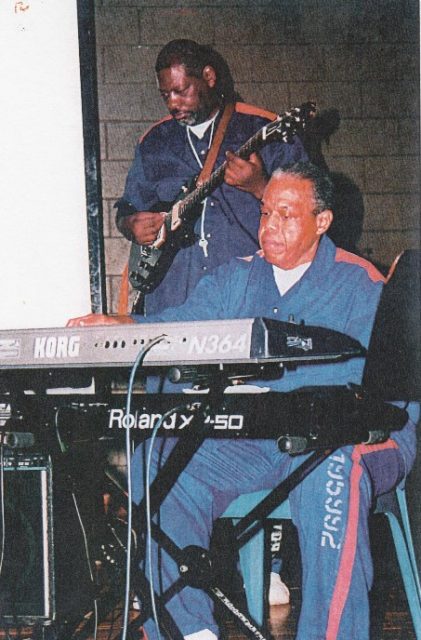

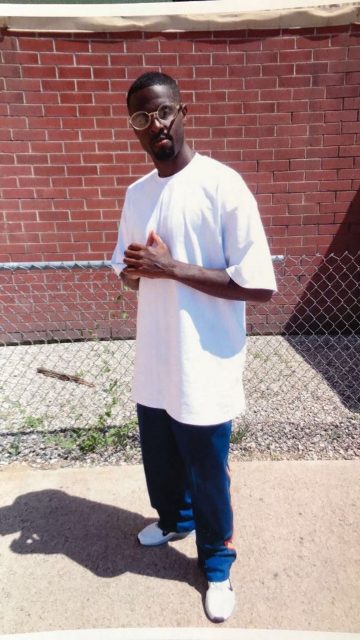

Charles Lewis, an accomplished musician, plays guitar with Bill Lemons on keyboard in prison band. Lewis is now 58, Lemons is 73, still serving life. Lewis played every instrument beginning in childhood. A promising musical career was cut short by his false conviction, engineered by then DPD Sgt. Gil Hill, at the age of 17. On his release, Lewis still wants to pursue his musical career. He is an extremely accomplished “jailhouse” lawyer as well, having written hundreds of documents and briefs which are letter perfect and cite numerous legal precedents. His mother Rosie says she ran into a stranger when her car broke down, and the man told her “Your son is Charles Lewis? He’s the reason I’m out of prison!”

DETROIT—Supporters of Charles Lewis, wrongfully incarcerated for 41 years since the age of 17, whose court file mysteriously went missing, say they will #TakeTheKnee at his court hearing in front of Third Judicial Circuit Court Judge Qiana Lillard Friday, Oct. 6 at 9 a.m.

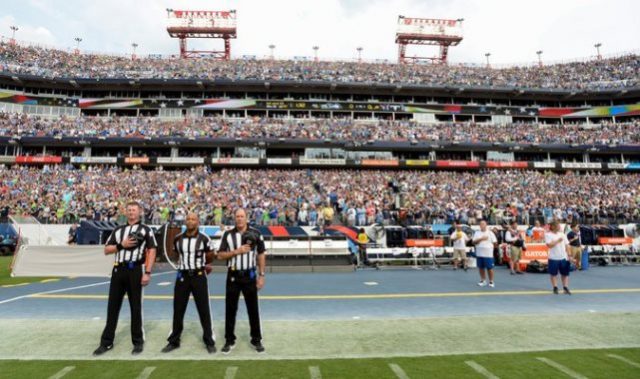

“I am the epitome of what Colin Kaepernick was protesting,” Lewis wrote in the article below, referring to the San Francisco 49er’s football star who initiated a wave of National Anthem protests by kneeling on one knee as the song was played during a game.

“The biggest problem that we have as African-Americans is the judicial system does not work for us,” Lewis said. “Regardless of why we find ourselves in the judicial system, whether it is because we are victims of police brutality, or being charged with a crime, the system of justice does not work for us.”

Judge Lillard called the Oct. 6 session, where Lewis will be present, to hear arguments from his Objection filed June 23, 2017 against her order to reconstruct his file and for his immediate release. He has based those arguments on legal precedents including two Michigan State Supreme Court rulings in People v. Fullwood (1974), which categorically forbids reconstruction of a criminal court case file, and People v. Adkins (1990), and a U.S. Supreme Court decision, Chessman v. Teets, 1957.

Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy and AP Tom Dawson are recommending that Lewis be re-sentenced to juvenile life without parole (JLWOP) despite the missing official court record.

Lewis recently retained attorney Victoria Burton-Harris, of McCaskey, PLLC, who won a police case against Scrill of New Era Detroit earlier this year, to represent him.

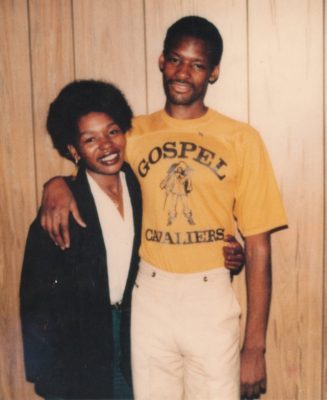

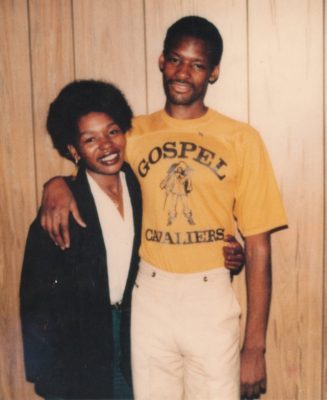

Rosie Lewis with her son Charles after his imprisonment in 1977. He played in the prison band “The Gospel Cavaliers” the.

“In the beginning, they never produced material evidence of the crime, and they had witnesses including a Detroit police officer who saw someone else shoot the victim,” Lewis’ mother Rosie Lewis said. “My son is innocent. Judge Gershwin Drain dismissed his case on April 3, 2000 so why do they have him in prison? They lost three cartons of court files that I reviewed. They’ve lost the case if they don’t have the court record. You can’t come up with what isn’t there.”

In her opinion rendered on an appeal of Lewis’ case Aug. 6, 2016, Judge Deborah Thomas, who at the time had Lewis’ complete record, wrote that Lewis should have been considered acquitted after his first trial in March, 1977, and subject to double jeopardy provisions, because his trial Judge Joseph Maher dismissed the jury during its deliberations without cause.

Only a brief portion of that trial transcript is included in the “re-constructed” file that Judge Lillard is considering certifying.

Judge Thomas also opined that his conviction and sentence should have been dismissed after another judge’s failure to hold a Pearson evidentiary hearing involving witnesses excluded from his second trial in front of Maher within the state-ordered time limits.

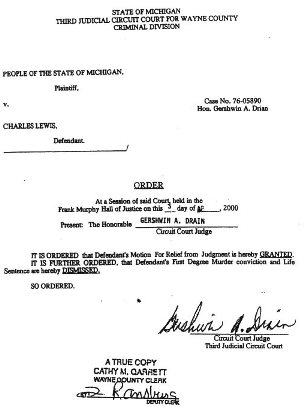

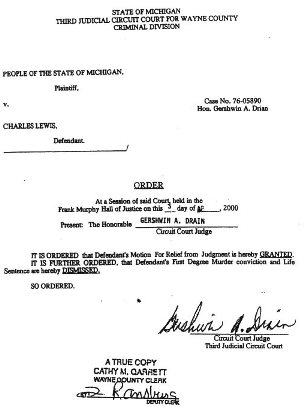

Lewis says he filed a motion for relief from judgment in front of Judge Gershwin Drain on that matter, and that Drain dismissed his conviction and sentence April 3, 2000. He says he did not receive a copy of that order until 10 years later. Without giving any proof, AP Tom Dawson contends that order was forged, citing an unsigned opinion by Drain in 2012. The opinion claims Drain was never on his case, but there is no way of verifying that because Lewis’ Register of Actions has been obliterated from 1976 to 2000. The only copies still extant show Lewis’ case WAS dismissed by Drain on April 3, 2000, and another that claims he was convicted by a jury in front on Drain on April 3, 2000.

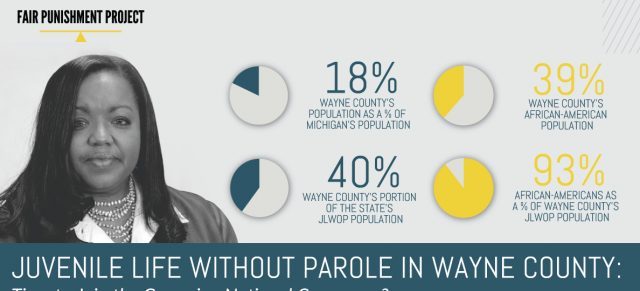

Lewis is one of 247 juvenile lifers across Michigan, out of 363, that prosecutors have recommended be re-sentenced to JLWOP, flouting two U.S. Supreme Court decisions outlawing JLWOP. So far, none of the 247 has seen any action on their case. Attorney Deborah LaBelle and the Michigan ACLU are awaiting a decision from the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals on their case, which challenges the very existence of juvenile life without parole, objects to the 2014 state statutes, and demands that these juvenile lifers be spared any further “cruel and unusual” punishment. Six of them have died waiting for the promise of Miller v. Alabama (2012) to come to fruition.

Lewis is one of 247 juvenile lifers across Michigan, out of 363, that prosecutors have recommended be re-sentenced to JLWOP, flouting two U.S. Supreme Court decisions outlawing JLWOP. So far, none of the 247 has seen any action on their case. Attorney Deborah LaBelle and the Michigan ACLU are awaiting a decision from the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals on their case, which challenges the very existence of juvenile life without parole, objects to the 2014 state statutes, and demands that these juvenile lifers be spared any further “cruel and unusual” punishment. Six of them have died waiting for the promise of Miller v. Alabama (2012) to come to fruition.

After 41 years in prison, Lewis estimates that at least 10 percent of the juvenile lifers he has met are innocent. However, there is no provision in state statutes passed in 2014, which are currently being contested in the U.S. Sixth District Court of Appeals, to allow consideration of innocence. Lewis notes also that he was granted re-sentencing under the U.S. Supreme Court Miller v. Alabama ruling in 2012, by Third Judicial Circuit Court Judge Edward Ewell, Jr., and should not be subject to the 2014 state statutes.

In his objection, Lewis also wrote, “Judge Lillard’s staunch refusal to acknowledge or apply United States Supreme Court precedent . . . or Michigan Supreme Court precedent is clear evidence that Judge Lillard is bias[ed] and has a clear conflict of interest. Judge Lillard cited the dissenting opinion in a 1911 case that was based on a repealed statute to pierce the veil of attorney/client privilege and order defense counsel to turn over all of the files and records in her possession to the prosecution. Who does that?”

Lewis referred to Judge Lillard’s eight years in as an AP in Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy’s office before she took the bench, and while he was still appealing his case through that office. In the Nov. 18 opinion by Judge Lillard, she denied both defense attorney Valerie Newman’s motion to sentence Lewis to a term of years under the state statutes, and Lewis’ own motion for dismissal, and granted the prosecution’s motion for renewed JLWOP.

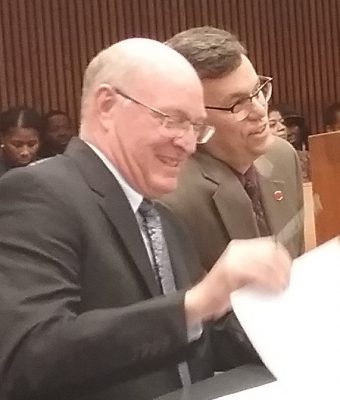

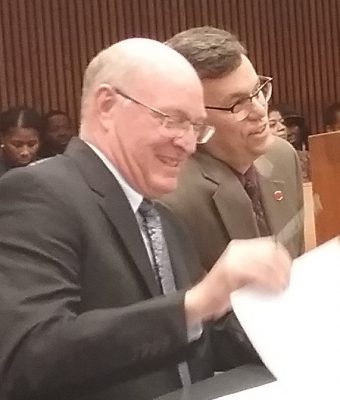

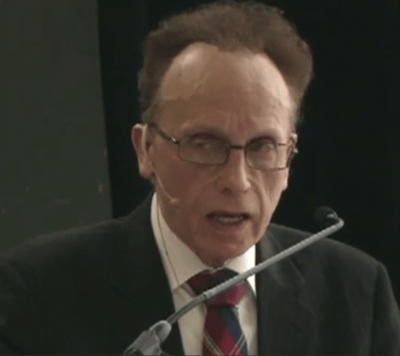

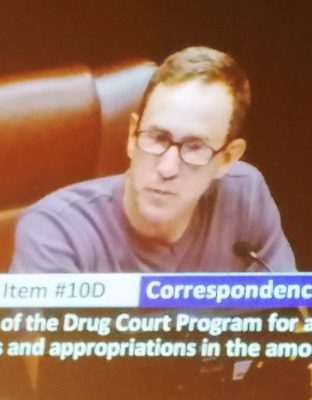

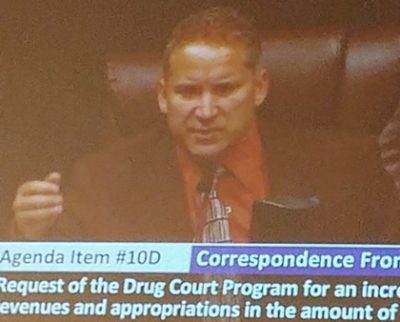

AP’s Tom Dawson and Jason WIlliams chortle at earlier Lewis hearing. As Judge Lillard did in the COA Walker case, Dawson sought to demean Lewis as a man “with unclean hands” in his response to Lewis’ objection.

Lewis earlier asked for Lillard to recuse herself from his case.

In a Dec. 2016 Court of Appeals case on Harold Lamont Walker, that defendant also accused Judge Lillard of siding with the prosecution. He was charged with one instance of felony firearm. Judge Lillard sentenced him to four to 75 years after an exchange cited by COA Judge Elizabeth Gleicher in a dissenting opinion, in which she recommended that the case be remanded to another judge.

The exchange, as quoted by Gleicher in part, included an extended period of Lillard repeatedly calling the defendant a “clown,” and otherwise demeaning him personally as a human being and a Black man.

Gleicher also cited what she said were Judge Lillard’s faulty jury instructions. They appeared to encourage the jury, which had first declared a deadlock, to take a lunch break, calm down, and come back in one hour to finish their deliberations. Gleicher recommended that the case be remanded to a different judge. See http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/COA-Harold-Lamont-Walker-dissenting.pdf.

Lewis says in his objection, “Anything short of an immediate dismissal is a travesty of justice.”

Related documents:

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/C-Lewis-Objections-6-23-17.compressed.pdf

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/Pros.-response-9-11-17-to-CL-objection-of-6-23-17.compressed.pdf

http://voiceofdetroit.net/wp-content/uploads/DThomasOpinion-1.pdf

New England Patriots kneel for National Anthem, as part of wave of protests against white supremacy and racist oppression, initiated by San Francisco 49’ers player Colin Kaepernick. #TakeTheKnee @Kaepernick7

A KNEE IN PROTEST OF INJUSTICE

BY CHARLES LEWIS

SEPTEMBER 29, 2017

VOD: Detroiter Charles Lewis has been wrongfully incarcerated since the age of 17 in 1976. He is asking that all who support him as well as millions of prisoners and other victims of racist oppression across the U.S. come to his next court hearing Fri. Oct. 6, 2017 in front of Third Judicial Circuit Qiana Lillard, Rm. 502, Frank Murphy Hall, St. Antoine and Gratiot, Detroit, MI.

Charles Lewis

I’m watching this debate about the actions of NFL Players taking a knee and why they are kneeling. They are kneeling to protest injustice. There is one brand of inferior Justice that African-Americans receive when they are pulled over by the police, killed by the police, or charged with crimes, that white America does not receive.

I am the epitome of what Colin Kaepernick was protesting. The biggest problem that we have as African-Americans is the judicial system does not work for us. Regardless of why we find ourselves in the judicial system, whether it is because we are victims of police brutality, or being charged with a crime, the system of justice does not work for us.

My name is Charles Lewis, I am a 58 year old juvenile lifer that has been locked up for the past forty-one years for a murder that Judge Deborah Thomas said that it was impossible for me to have committed. To say that the judicial system has failed me would be an understatement. The system failed me when seventy year old Arthur Arduin was appointed to represent me because I had no money to hire my own lawyer.

My seventy year old lawyer never interviewed any witnesses. My lawyer never interviewed the eye witnesses that made statements identifying another man as the shooter. One of the eye witnesses was an off duty Detroit Police Officer. He testified at two trials that he was talking to Gerald Swpitkowski when Leslie Nathanial pulled up next to him and shot him from his white Mark IV.

My first trial began March 9, 1977. Judge Joseph E. Maher dismissed my first jury on March 23, 1977. No reason has ever been given for the dismissal of the first jury. I will go to my grave believing that the first jury found me not guilty. The judicial system failed me forty years ago.

Judge Joseph Maher (photo 1976)

A second jury was empaneled before visiting Judge Ollie Bivins on May 23, 1977. The second jury was dismissed right after they were sworn in. The judicial system broke down and completely failed me.

A third jury was empaneled on July 5, 1977 before Judge Joseph E. Maher. The jury was already seated when I stepped inside the courtroom. My lawyer argued to the jury that I was guilty. The judicial system completely failed me during my third trial.

During the third trial the prosecutor asked the judge if he could exclude the testimony of several witnesses. At seventeen years old I stood up in that courtroom and told the judge that I wanted all of the witnesses brought in to testify. Judge Maher assured me that all of the witnesses would be brought in to testify. None of those witnesses were allowed to testify. At that point the judicial system broke down and failed me.

Raymond Miller was the seventy year old appellate lawyer that was appointed to represent me on my appeal of right. The Detroit News did a survey of all appellate lawyers practicing appellate law and concluded that Raymond Miller was the worst lawyer practicing appellate law. The system failed me when the worst lawyer practicing appellate law was appointed to represent me on my appeal.

Raymond Miller filed a thirteen page brief and raised fourteen issues. The issues and the brief were poorly constructed. It was impossible to understand the issues that Miller raised. Miller never came to see me. All appellate lawyers practicing appellate law must visit their client at least one time. Miller also refused to raise any of the issues that I wanted raised. The judicial system broke down on the appellate level and failed me.

Manual’s Black Student Union @dmhs_bsu takes a knee in solidarity with @Kaepernick7 and against police brutality and oppression. #TakeTheKnee

I got a job in the law library and began researching my own case. In 1979 I filed a brief before Judge Edward M. Thomas. In the brief I argued that I was entitled to a Pearson evidentiary hearing pursuant to People versus Pearson 404 Mich 698 (1979). Judge Thomas denied my motion and appointed Rose Mary Robinson to represent me.

Rose Mary Robinson appealed judge Edward Thomas’ denial to the Michigan Court of Appeals and won a Pearson evidentiary hearing pursuant to People versus Pearson.

On August 22, 1980 the Michigan Court of Appeals granted me a Pearson evidentiary hearing pursuant People versus Pearson and remanded my case to the trial court before judge Edward Thomas. In Pearson the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that once a Pearson evidentiary hearing is granted the prosecutor has 30 days to conduct the hearing or the case is automatically dismissed. The prosecutor’s 30 days began on September 22, 1980.

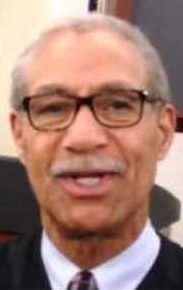

Now U.S. District Court Judge Gershwin Drain

Judge Gershwin Drain’s order dismissing case

My conviction was not lawfully vacated on September 22, 1980. Instead, my lawyer Rose Mary Robinson was removed.

Judge Edward M. Thomas decided to allow the prosecutor to conduct a Pearson evidentiary hearing five months after the Michigan Court of Appeals ordered it. I argued that my conviction should have been dismissed. Then the system of justice broke down and the transcripts of the hearing came up missing.

I finally got a copy of the evidentiary hearing after fifteen years. I filed a motion for relief from judgment and the motion was assigned to Gershwin A. Drain. Judge Drain, a black judge, dismissed my conviction. I didn’t receive a copy of the order when it was issued. I got a copy of the order ten years after it was issued.

I sent a copy of the order dismissing my conviction signed by Judge Drain, certified received by the Wayne County Clerk’s Office to Judge Drain. Judge Drain accused me of forging his signature on the order. Forgery in the State of Michigan is governed by statute and must be proven.

All of my court files and records for all of my cases were intentionally destroyed by the Wayne County Clerks Office.

My current Judge Qiana Lillard was not alive when I got arrested. Judge Lillard ordered my lawyer Valerie Newman to turn all of my personal records over to the prosecution so that the prosecution could make a new Court file. The judicial system has completely broken down at my expense.

I want thank Colin Kapernik and Black Lives Matter and the NFL for taking a knee to protest injustice.

Attica Rebellion, September, 1971; today 2.5 million people in the U.S. are incarcerated, 25 % of the world’s total; the U.S. has only 5% of the world’s population.

RELATED STORIES:

CASES SEEK ABSOLUTE BAN ON LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE SENTENCES FOR YOUTH FROM U.S. SUPREME COURT

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2017/06/23/juvenile-lifers-ex-offenders-advocates-begin-new-chapter-in-battle-for-justice-june-18/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2017/08/08/juvenile-lifer-re-sentencings-drag-on-in-michigan-nation-as-states-snub-u-s-supreme-court/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2017/07/15/the-troubled-resentencing-of-americas-juvenile-lifers-the-nation/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2017/02/20/charles-lewis-must-be-freed-due-to-loss-of-court-file-innocence-sado-withdraws-from-case/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2017/02/12/rogue-justice-free-another-innocent-detroiter-charles-lewis-now-hearing-wed-feb-15-9-am/

‘ROGUE JUSTICE!’ FREE ANOTHER INNOCENT DETROITER, CHARLES LEWIS, NOW! HEARING WED. FEB. 15 @ 9 AM.

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2017/01/20/judge-deborah-thomas-charles-lewis-should-have-been-acquitted-sentence-vacated-in-1976-murder/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2017/01/12/wayne-co-juvenile-lifers-lives-at-stake-only-two-paroled-charles-lewis-hearing-thurs-feb-9-2017/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2016/10/26/free-charles-lewis-mich-juvenile-lifers-re-sentenced-to-die-in-prison-rally-fri-oct-28/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2016/10/13/support-for-charles-lewis-mich-juvenile-lifers-strong-at-hearing-oct-11-bring-them-home-now/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2016/10/07/stop-new-death-penalty-for-mich-juvenile-lifers-rally-tues-oct-11-for-charles-lewis-others/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2016/09/10/new-hope-for-michigan-juvenile-lifer-charles-lewis-as-others-await-long-delayed-justice/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2016/09/04/free-charles-lewis-wayne-co-juvenile-lifers-dying-in-prison-rally-at-hearing-tues-sept-6/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2016/08/02/michigan-files-for-jlwop-for-80-of-juvenile-lifers-fed-court-wants-all-parole-eligible/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2016/07/26/worthy-others-want-large-portion-of-juvenile-lifers-to-die-in-prison-despite-ussc-rulings/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2016/05/24/free-charles-lewis-innocent-juvenile-lifer-who-has-spent-41-years-in-state-prisons/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2016/04/30/why-is-juvenile-lifer-charles-lewis-still-in-prison-16-yrs-after-his-case-was-dismissed/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2012/10/28/michigans-juvenile-lifers-want-state-to-comply-with-u-s-supreme-court-ruling/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2012/08/16/michigan-challenges-u-s-supreme-court-ruling-on-juvenile-life-without-parole/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2012/07/02/us-supreme-courts-juvenile-lifer-decision-brings-hope-to-thousands/

http://voiceofdetroit.net/2012/07/02/nations-high-court-ends-mandatory-life-without-parole-sentences-for-youth/

#FREECHARLESLEWISNOW, #FREEMICHIGANJUVENILELIFERSNOW, #ENDMASSINCARCERATION, #TAKETHEKNEE

Lewis is one of 247 juvenile lifers across Michigan, out of 363, that prosecutors have recommended be re-sentenced to JLWOP, flouting two U.S. Supreme Court decisions outlawing JLWOP. So far, none of the 247 has seen any action on their case. Attorney Deborah LaBelle and the Michigan ACLU are awaiting a decision from the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals on their case, which challenges the very existence of juvenile life without parole, objects to the 2014 state statutes, and demands that these juvenile lifers be spared any further “cruel and unusual” punishment. Six of them have died waiting for the promise of Miller v. Alabama (2012) to come to fruition.

Lewis is one of 247 juvenile lifers across Michigan, out of 363, that prosecutors have recommended be re-sentenced to JLWOP, flouting two U.S. Supreme Court decisions outlawing JLWOP. So far, none of the 247 has seen any action on their case. Attorney Deborah LaBelle and the Michigan ACLU are awaiting a decision from the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals on their case, which challenges the very existence of juvenile life without parole, objects to the 2014 state statutes, and demands that these juvenile lifers be spared any further “cruel and unusual” punishment. Six of them have died waiting for the promise of Miller v. Alabama (2012) to come to fruition.

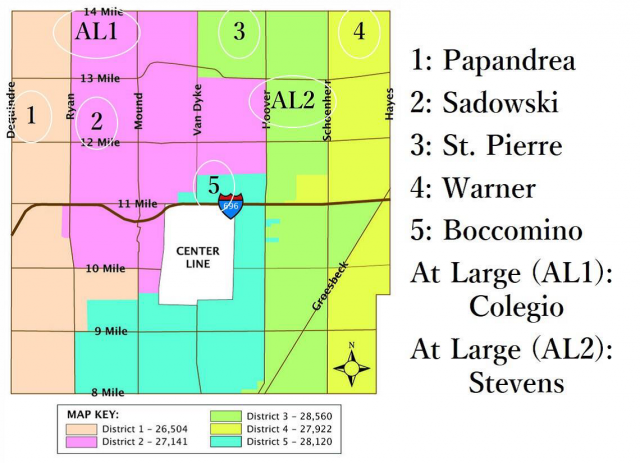

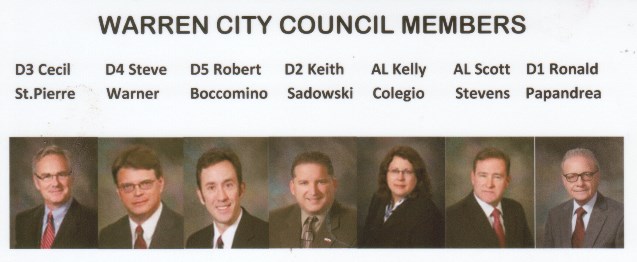

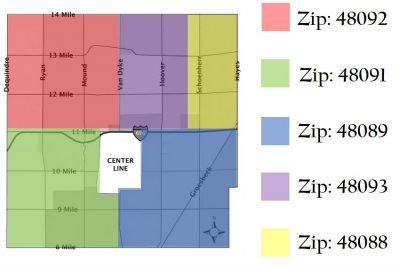

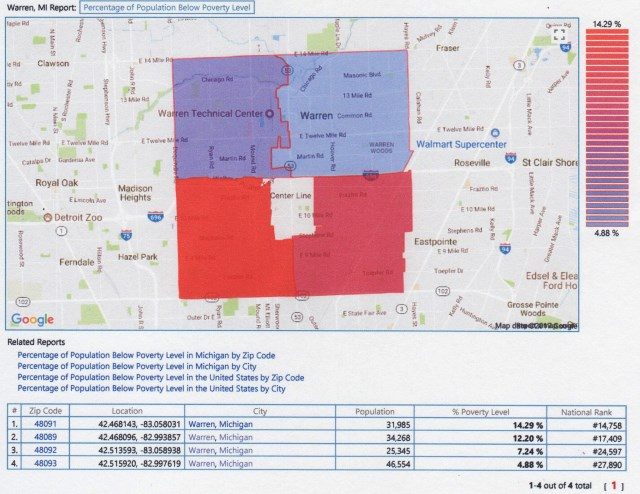

Warren Mayor Jim Fouts, who recently was the focus of a scandal arising from alleged tapes of him making racist remarks, also lives north of I-696 as well, at 28170 Louise Drive, Warren, MI 48092. Fouts has discouraged Bell from raising his current complaint with the Justice Department, and earlier from challenging the Warren City Code’s ban on anyone with a felony record running for office in the city.

Warren Mayor Jim Fouts, who recently was the focus of a scandal arising from alleged tapes of him making racist remarks, also lives north of I-696 as well, at 28170 Louise Drive, Warren, MI 48092. Fouts has discouraged Bell from raising his current complaint with the Justice Department, and earlier from challenging the Warren City Code’s ban on anyone with a felony record running for office in the city.

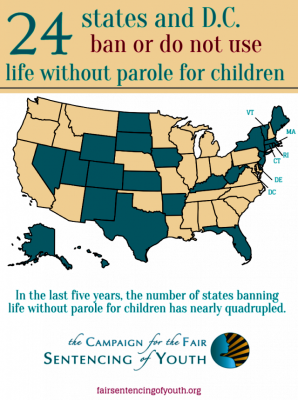

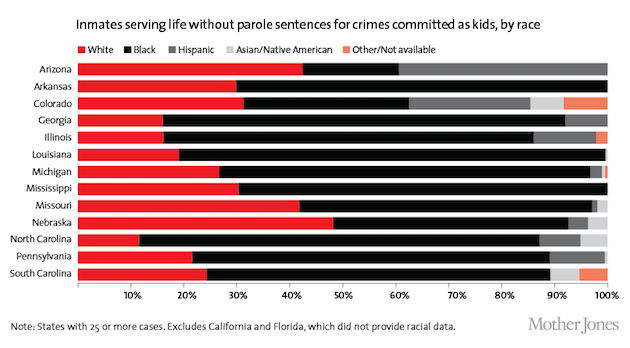

In 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that mandatory LWOP sentences for juvenile offenders are unconstitutional and ordered the resentencing of the nation’s 2,500 prisoners affected by the ruling. Prosecutors from several states ignored the landmark decision, including Michigan, claiming that it was not retroactive and did not apply to cases that had previously exhausted the direct appeal process.

In 2012 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that mandatory LWOP sentences for juvenile offenders are unconstitutional and ordered the resentencing of the nation’s 2,500 prisoners affected by the ruling. Prosecutors from several states ignored the landmark decision, including Michigan, claiming that it was not retroactive and did not apply to cases that had previously exhausted the direct appeal process.

They specifically characterized Michigan and Louisiana as being among “a handful of extreme outliers that are flouting the [U.S. Supreme] Court’s dictate to limit JLWOP to the rare juvenile offender.”

They specifically characterized Michigan and Louisiana as being among “a handful of extreme outliers that are flouting the [U.S. Supreme] Court’s dictate to limit JLWOP to the rare juvenile offender.”

After I understood that this prosecutor’s language was an attack on my character, I began to bear witness to Hosea 4:6 which states, “My people are destroyed for a lack of knowledge.”

After I understood that this prosecutor’s language was an attack on my character, I began to bear witness to Hosea 4:6 which states, “My people are destroyed for a lack of knowledge.”